AARP Hearing Center

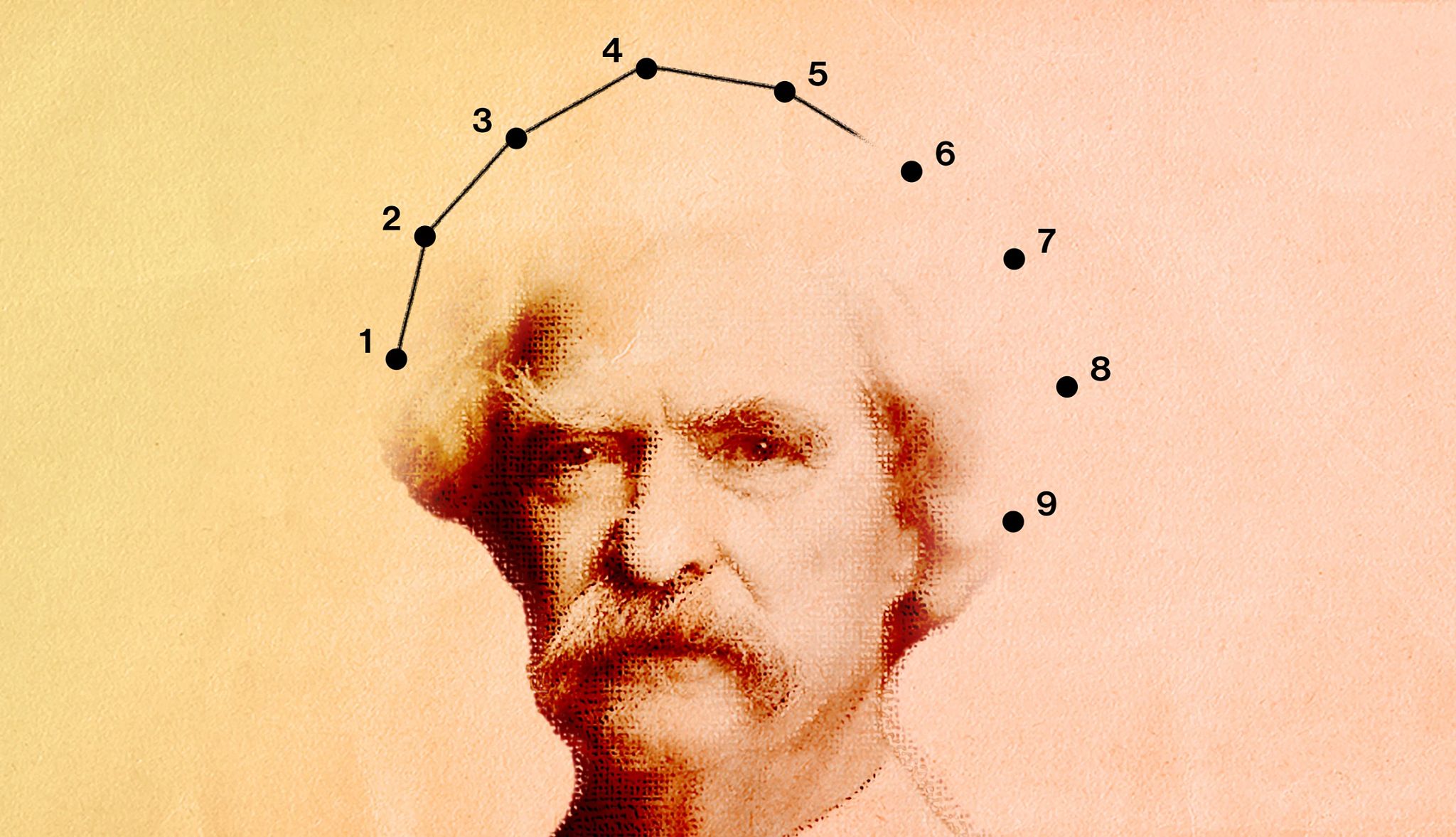

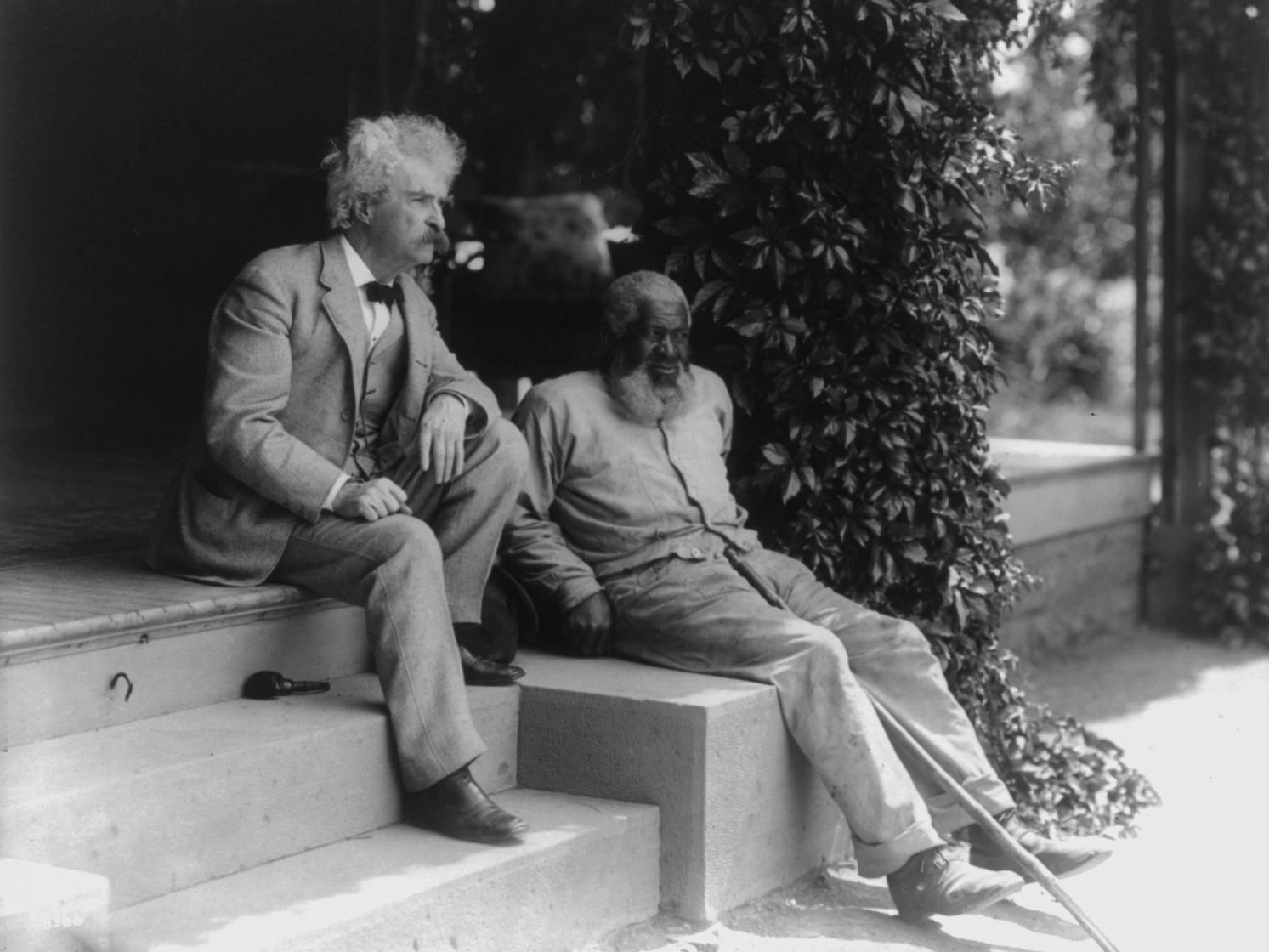

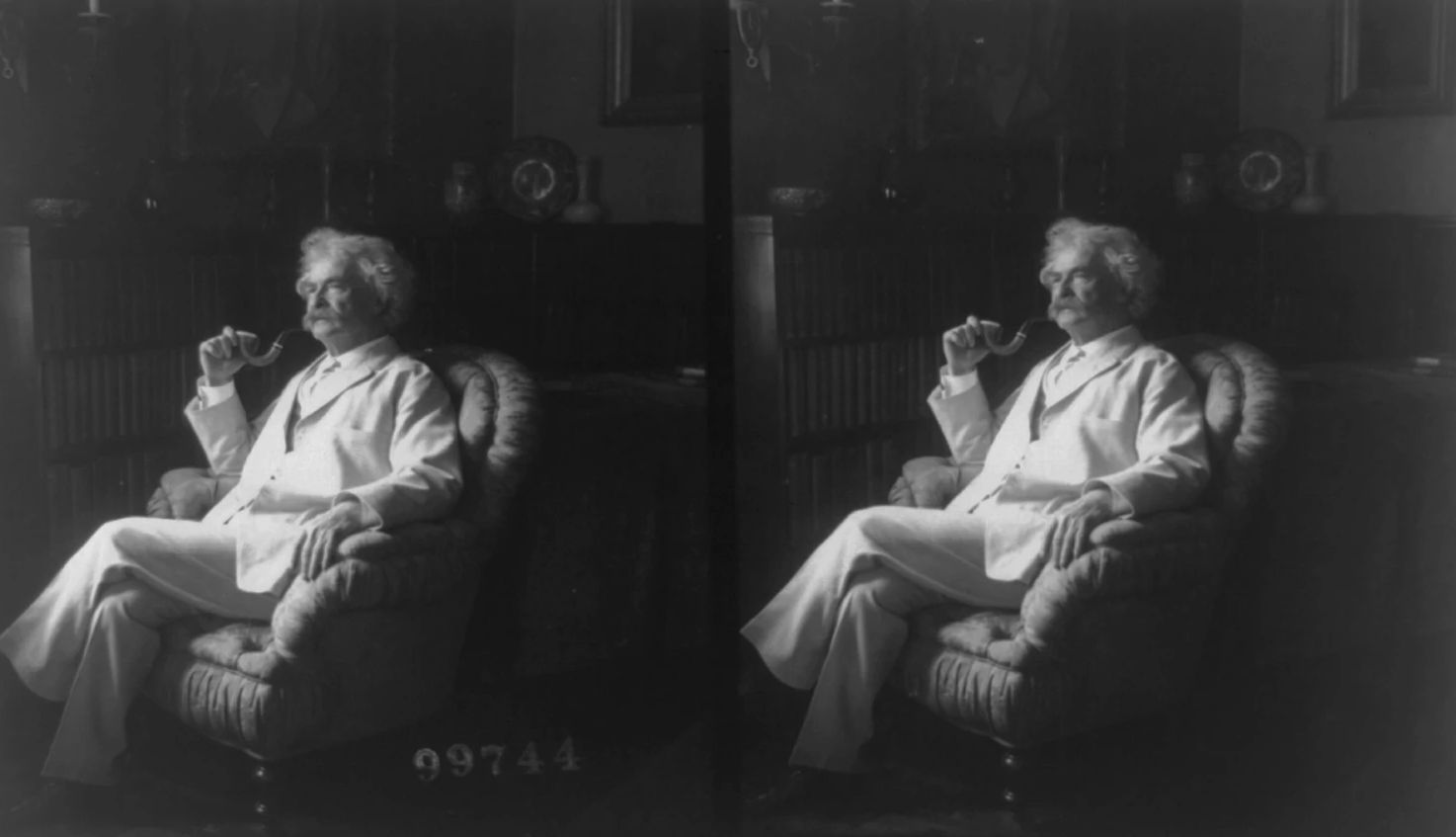

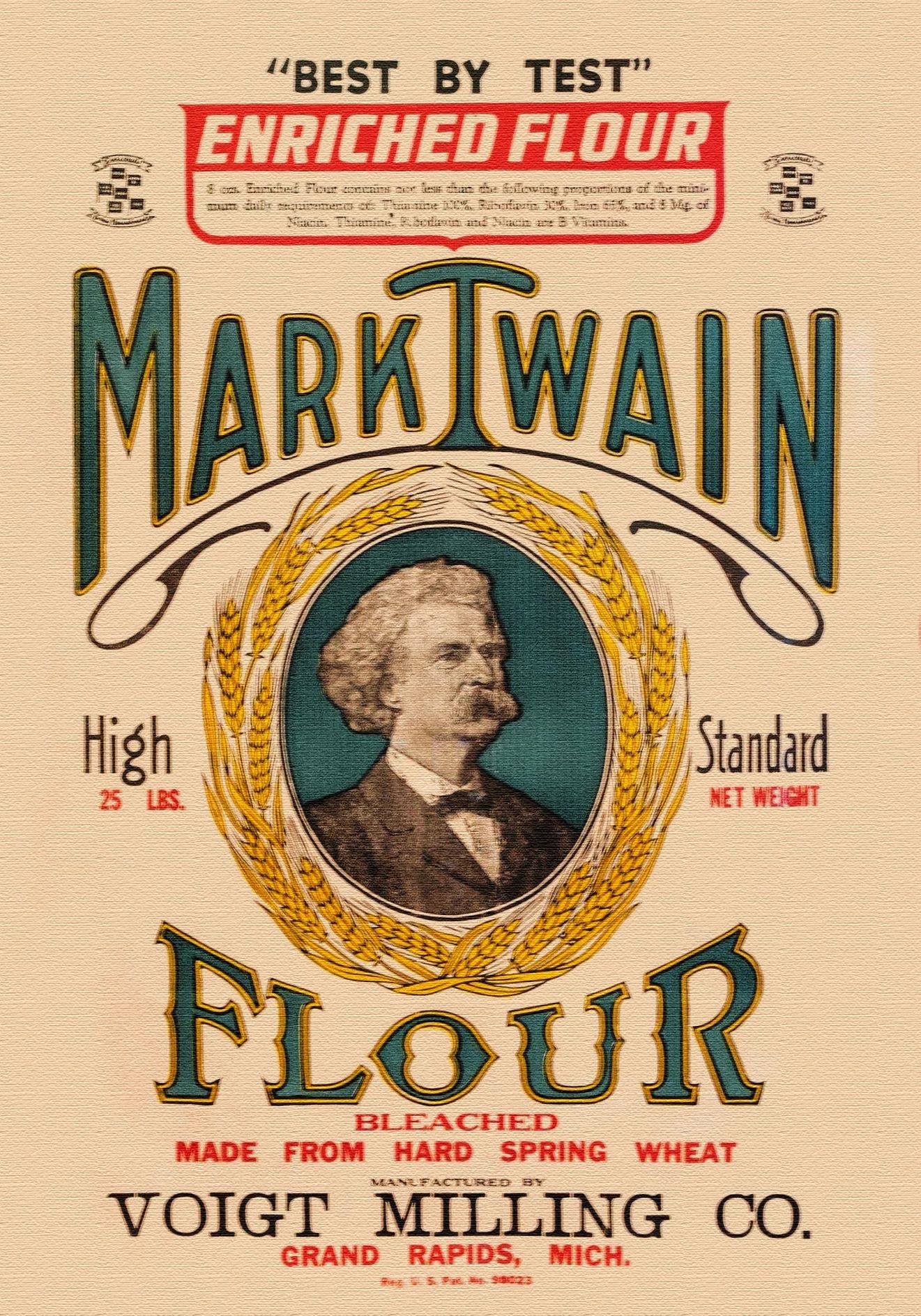

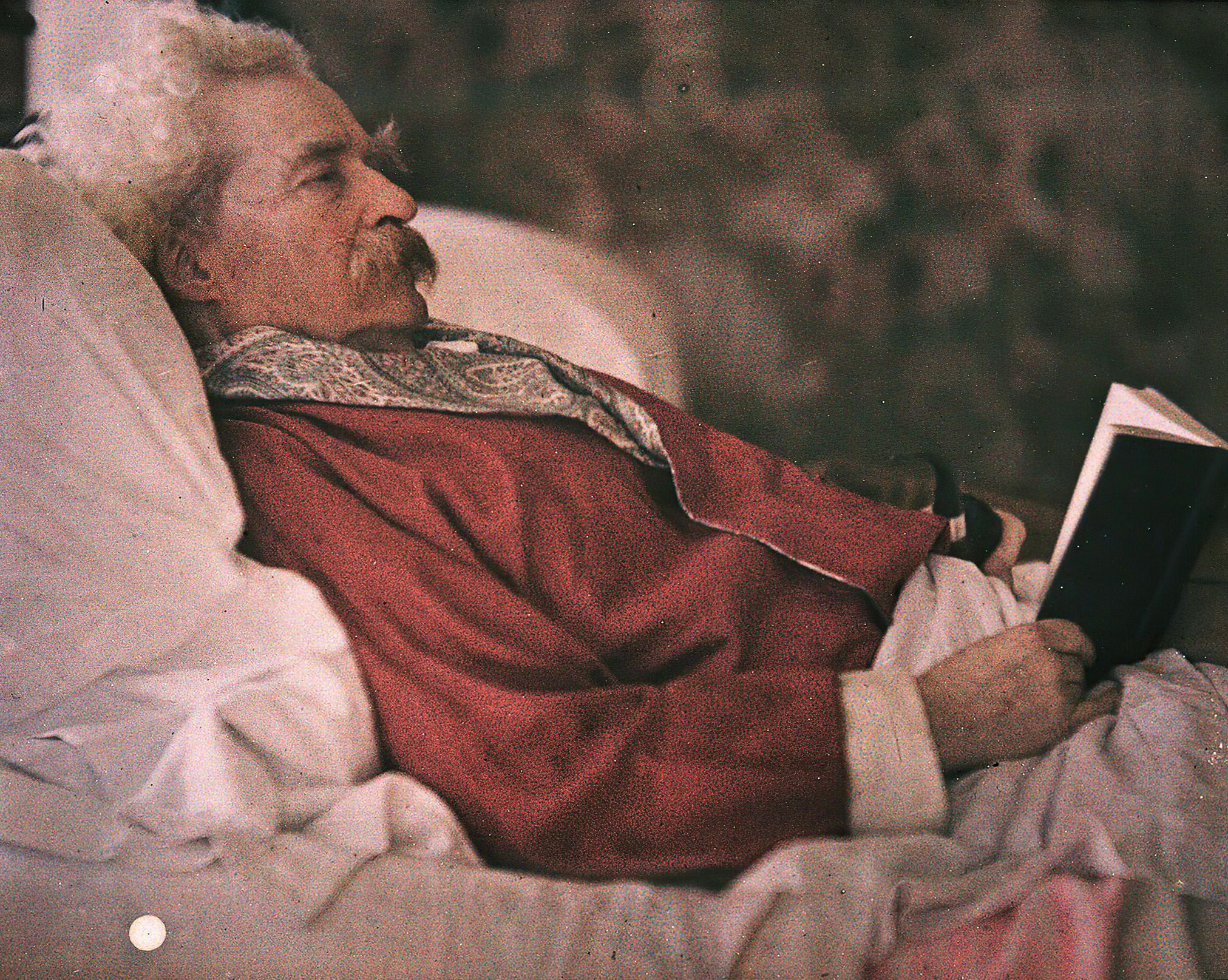

With his trademark white suits, droopy mustache and dandelion hair, the beloved humorist and author Mark Twain (1835–1910) is still an instantly recognizable figure more than a century after his passing, at age 74. Today, he’s probably best known as the writer of two classic American novels, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the latter of which Ernest Hemingway called the source of “all modern American literature.... There has been nothing as good since.”

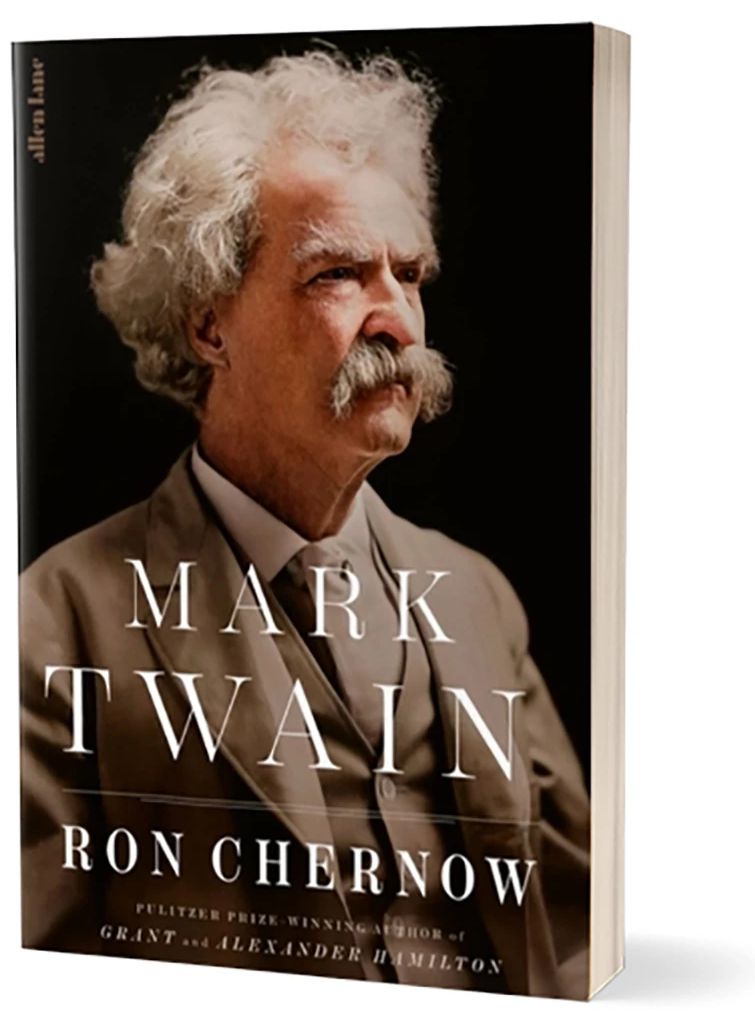

But Twain was a more complex character than his image as a witty quipster and author of required reading for English classes might suggest, according to Ron Chernow’s voluminous new biography, Mark Twain (out May 13).

The Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer (for Alexander Hamilton, which inspired the Broadway musical) offers a fascinating and, at more than 1,000 pages, hefty portrait of a volatile, complicated, irreverent man who not only “dared to state things that others only thought” but also held a surprisingly dark view of society and human nature, with “some mysterious anger, some pervasive melancholy” fueling his humor.

In short, Chernow writes, Twain “incarnated the best and sometimes the worst of America, all rolled into one.”

Here are 13 of the most intriguing things we learned about Twain’s life from the new book:

1. His relationship with his mother contributed to his esteem for women.

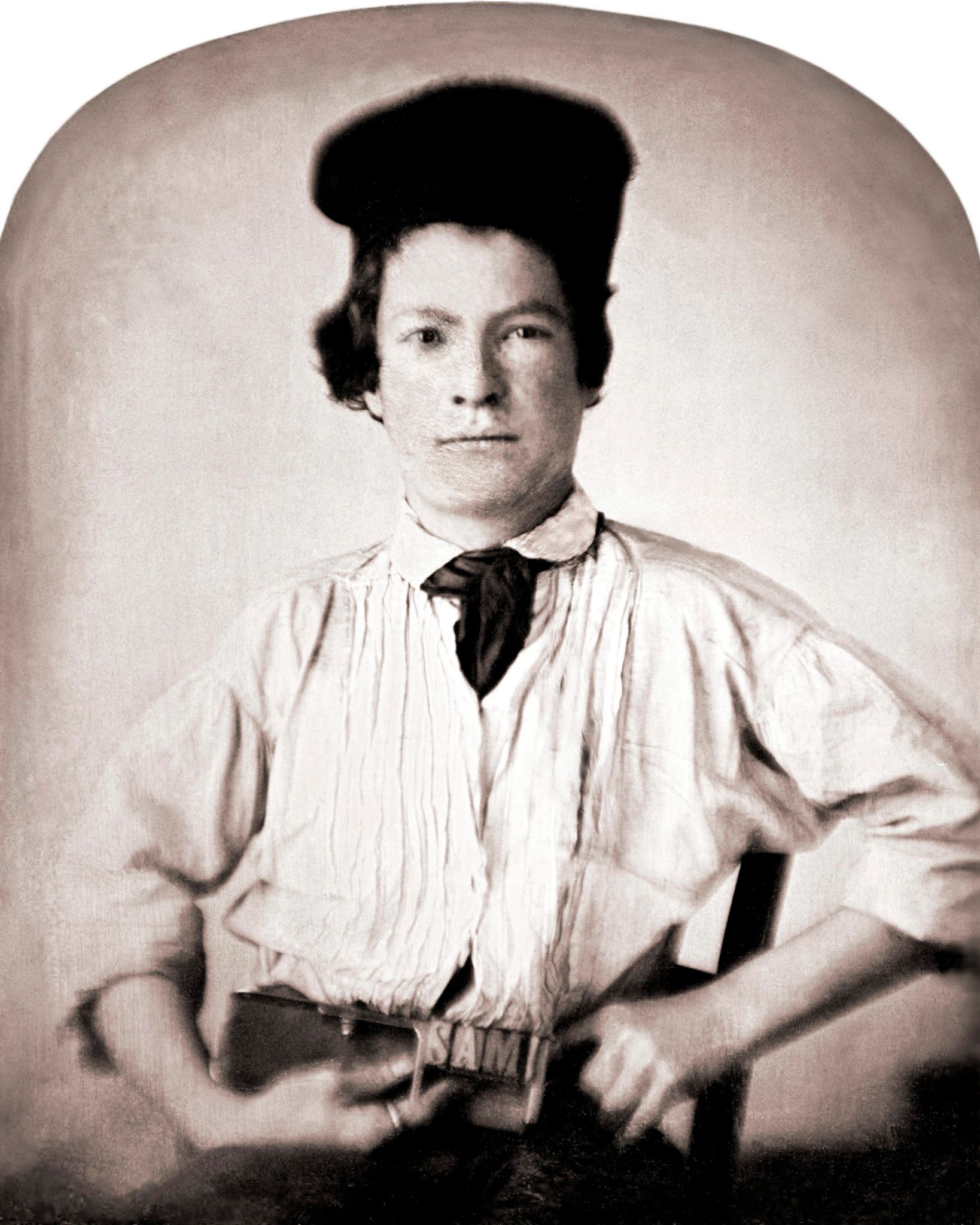

Born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in 1835, Twain, the sixth of seven children, was closer to his mother, Jane, than he was to his father. Their warm relationship would color his views of women all his life. From Jane, Chernow writes, “Twain learned that he could trust women and express a richer spectrum of emotion than with men. With his father, Sam had to suppress his personality; with his mother, he could flaunt it.” John Clemens, a judge who was cold and aloof to his son, died when the boy was 11, leaving the family in financial peril. Still, Twain was often “shy and awkward” with women, according to Chernow.

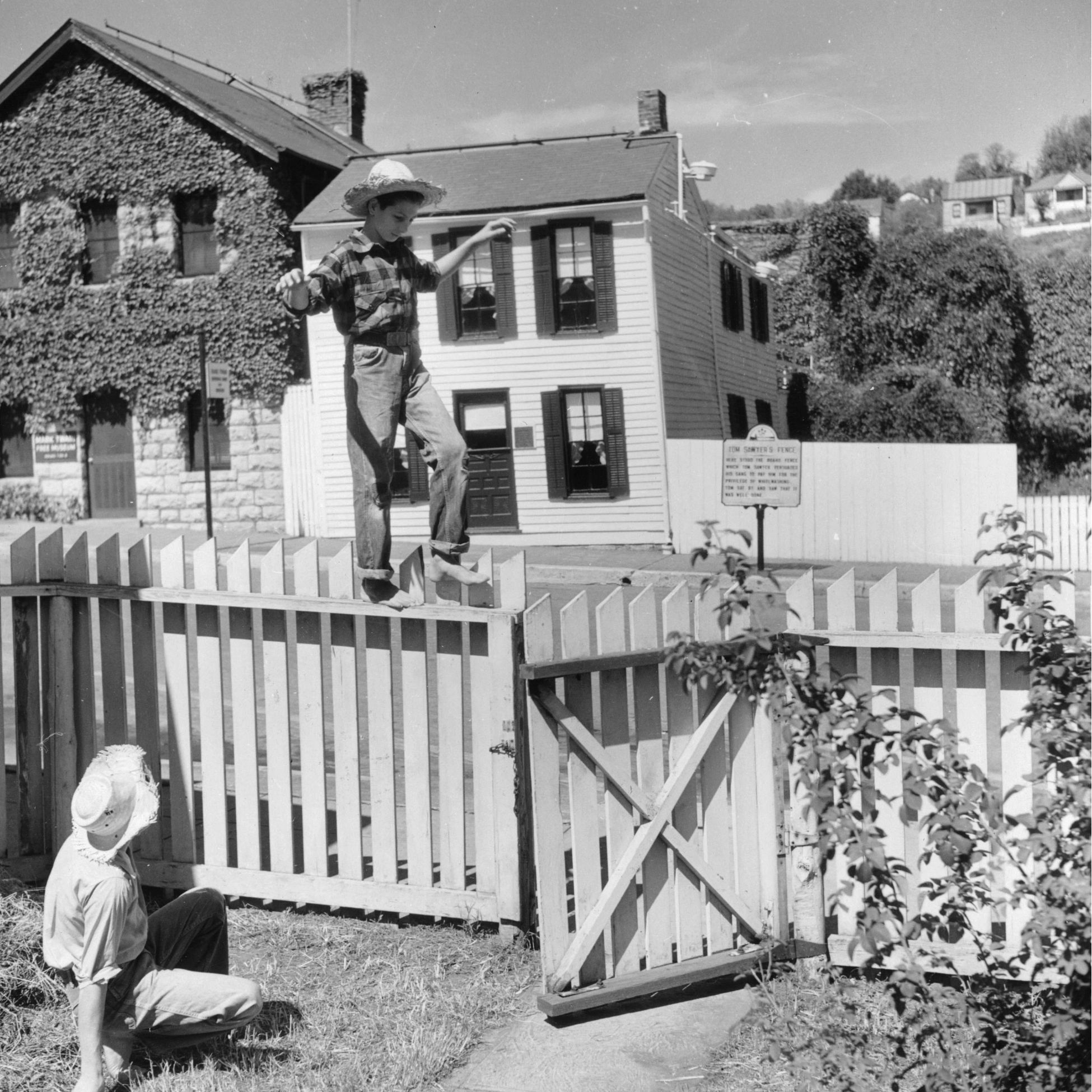

2. Twain idealized youth.

Twain romanticized his hometown of Hannibal, Mo., in his fiction, evoking it as “the white town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer’s morning.” He saw it as a childhood paradise where “youngsters went barefoot in summer and gorged on cornmeal cakes and catfish.” It left him with the sense, in Chernow’s assessment, that youth was “the only worthwhile period and that it was all downhill after that.”

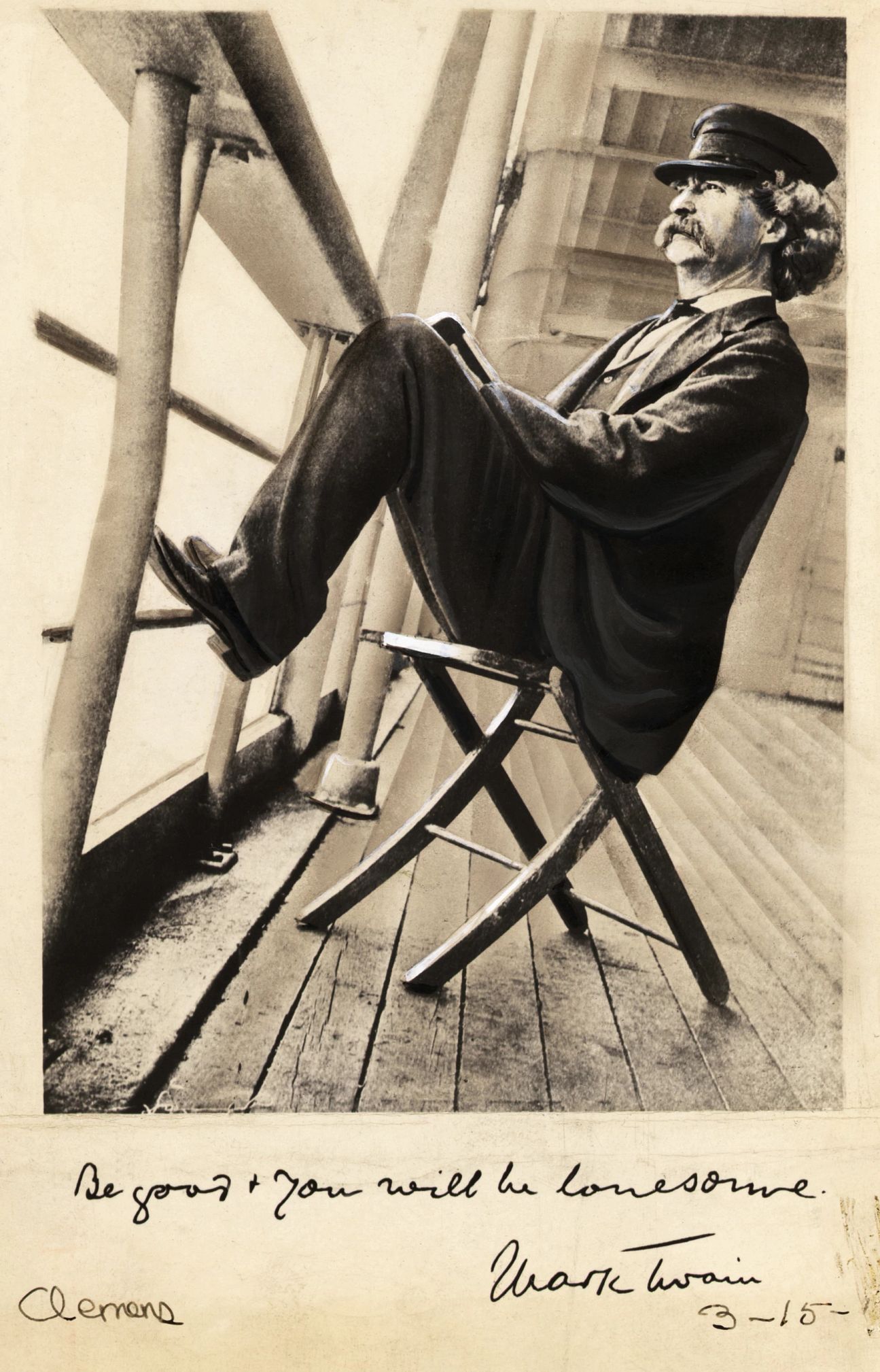

3. The water always beckoned him.

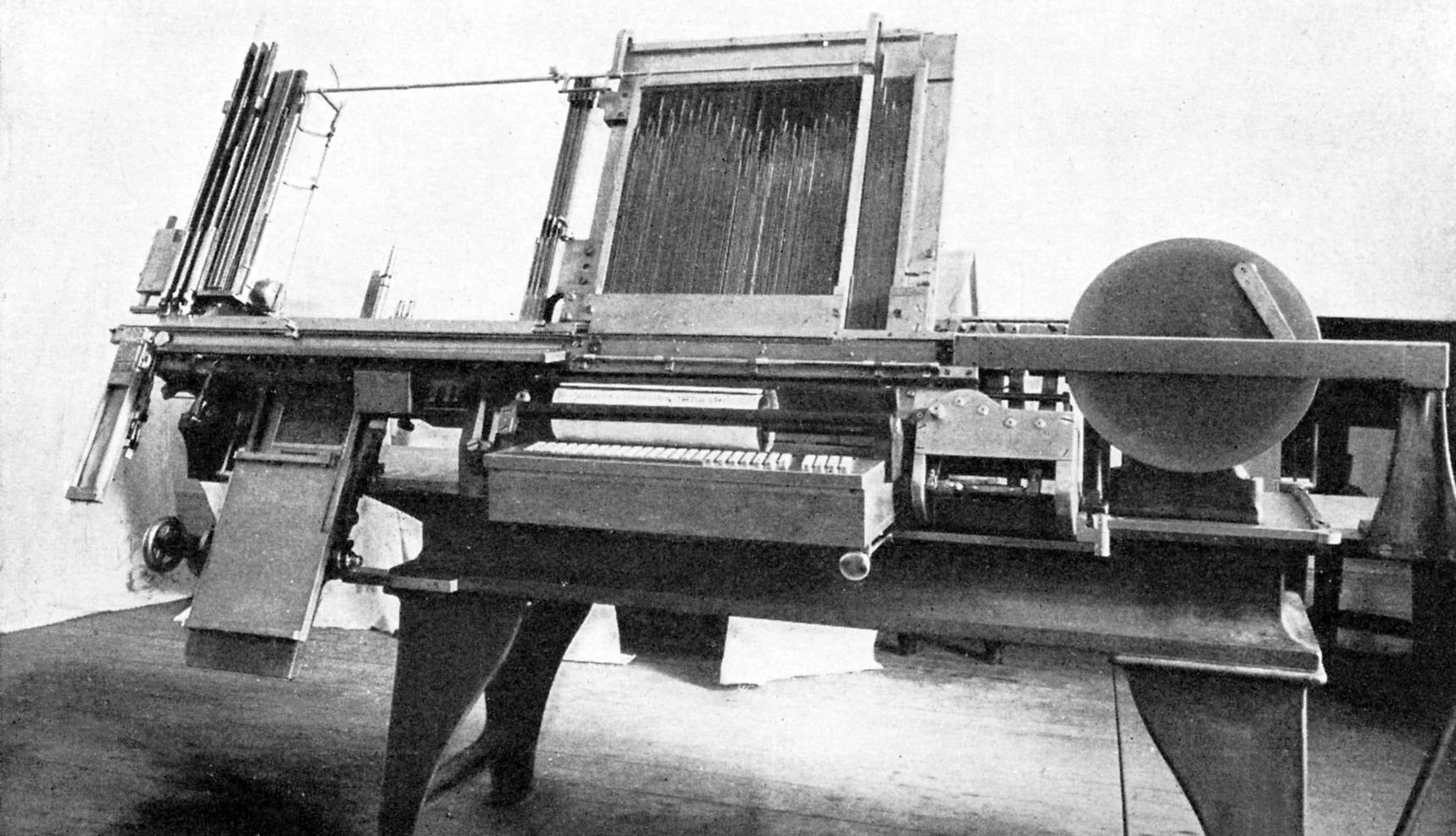

The Mississippi River (Hannibal is a port city) shaped not only Twain’s art, including his 1883 book Life on the Mississippi, but also his early ambitions: He dreamed of becoming a steamboat pilot and worked on the river until the Civil War broke out. The water cast a dreamy spell on him and even inspired his pen name, Chernow writes: “On the Mississippi River, the leadsman would sound the water’s depth by lowering a weighted rope, and if he cried ‘mark twain,’ it meant two fathoms or twelve feet, considered a safe depth.”

You Might Also Like

Dave Barry Has Thoughts on ‘Boomer Gyration'

Gen Zers remain seated while his generation does the mashed potato

Jimmy Fallon’s Idyllic Childhood Shaped His Success

The ‘Tonight Show’ host has a new children’s book all about granddads

For Melissa Rivers, It’s Time to Remember and Rebuild

Her TV tribute to mom Joan Rivers follows losing her home in the Palisades Fire