Staying Fit

Chapter Seven

JEN STOOD OUTSIDE WESTACOMBE COTTAGE, rang the bell and waited. The cottage was like something out of a child’s picture book, with low eaves and a thatched roof, but Jen didn’t appreciate its beauty. It was early afternoon and she was starving; breakfast seemed an age away. Sarah Grieve opened the door, and stood, blocking the way, silent and implacable.

‘I’m sorry to disturb you,’ Jen said, ‘but I do need to ask some questions.’

‘It’s not convenient.’

‘Eve’s dad is dead. Someone stuck a piece of glass in his neck. He bled all over her studio floor. That was more than inconvenient.’ Jen stopped speaking, and thought she’d ruined any chance she’d had to build a relationship with the woman. Even Ross would have done better and Matthew would be furious. But something about this woman, and missing lunch, and the remnants of a hangover, had got under her skin. She was about to apologize when Sarah Grieve stood aside.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

‘I suppose you’re just doing your job.’

‘The first few hours are important,’ Jen said. ‘We need to talk to you all.’

There was a dark hall, coats piled onto hooks, boots and shoes spilling out of a rack.

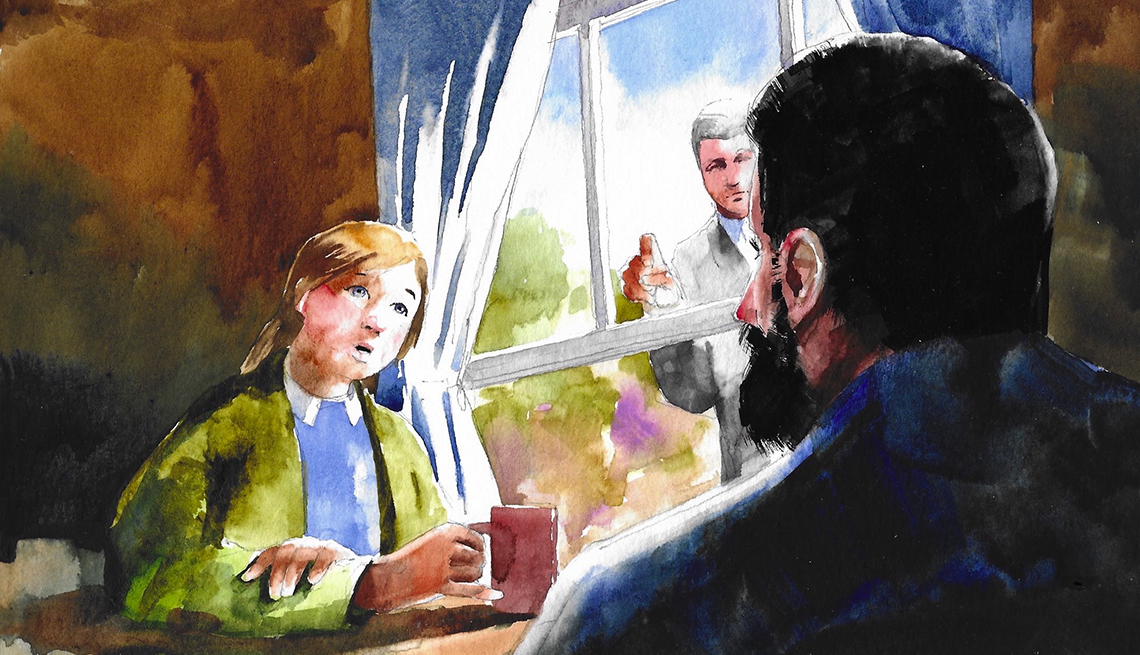

‘You’ll have to excuse the mess.’ The words were automatic; there was no sense that Sarah really cared what Jen thought about the state of her house. There was an open door leading into a kitchen. A tall, good-looking man with an impressive beard, and two small girls in shorts and T-shirts, sat at a scrubbed pine table. They’d been eating lunch and the remains of the meal were crammed at one end. At the other stood a pile of files, a basket of knitting wool, a doll with one arm and stray pieces of Lego.

The man stood up, stared. Jen picked up hostility. Was this how he always reacted to strangers in his home? ‘This is one of the detectives,’ Sarah said. ‘She wants to ask us some questions.’

‘I need to get back to work.’ But John Grieve hovered where he was. He didn’t move towards the door.

‘It won’t take long.’ The window in the room was small and there was no direct sunlight. After the brightness of the courtyard, it seemed very dark. Even in this heat, there was a faint smell of damp. The cottage might be idyllic from the outside, but it was cramped for a family of four. Jen was still struggling to make out all the detail in the kitchen. There seemed to be nowhere for her to sit.

‘Why don’t you go and play?’ Sarah said to the children. ‘You can use the laptop in our bedroom. Just half an hour.’

This seemed an unexpected treat and the girls ran off.

‘We don’t usually allow them screens.’ Sarah sat on one of the chairs and nodded for Jen to join them at the table. Jen thought briefly that if she’d been any kind of mother, she’d have limited her kids’ access to the internet, but it was too late for that now. Ben could barely make it through dinner without recourse to his phone. John Grieve returned to his chair. No move was made to clear the bread board, the rinds of cheese, the wilting salad. The woman leaned back in her chair. ‘So, what do you need to know?’

‘Did you hear or see anything unusual last night? Or the early hours of this morning?’

The couple looked at each other. Jen couldn’t work out what was going on. Some secret message passing between them? But they must have known the question would be asked and they would have had time to work out a story.

‘I was in bed by ten,’ John Grieve said. ‘I have to be up early for milking.’

‘I was later,’ Sarah said. ‘Frank wanted something in writing on the changes we’re planning to make to the dairy. I thought I’d make a start while it was clear in my head.’

‘What time did you finish?’

‘Midnight. Maybe a bit after.’

‘Did you hear a car in the yard? We know Nigel drove to Westacombe last night. At least, his vehicle is here.’

Sarah shook her head. ‘I was listening to music and had headphones on so I wouldn’t wake the kids.’

‘You didn’t see headlights?’

‘No, sorry. I was pretty focused on the screen.’

Grieve looked up. ‘I noticed Nigel’s car when I went out to the cows this morning. I thought he’d had an early start.’

‘You didn’t see him?’

‘No, I thought he’d be in the flat with Eve.’

‘Nothing unusual at all?’

‘Sorry.’ John Grieve got to his feet. ‘Look, I’ve got to go. It’s a busy time.’ He gave a brief nod to his wife and left the room. Through the kitchen door, Jen saw him pull on his boots in the hall and there was a sudden flash of sunlight as he went into the yard.

In the cluttered room, there was silence. Jen waited. She thought the woman might have more to say. Everything was still. She felt for a moment like a character in a gloomy Dutch painting. All brown interiors and rotting fruit. Her friend Cynthia fancied herself an expert in art, and dragged Jen round visiting exhibitions occasionally.

The silence stretched, until at last Sarah spoke. ‘Everyone thinks it’s paradise living here. We’re almost rent-free because I look after the big house for Frank when he’s not around, and he gives Wes and Eve a great deal too. But it’s not without its difficulties, living practically on top of each other. This place might look pretty, but it’s a bit low on mod cons. And Frank isn’t always easy.’

‘In what way not easy?’ This wasn’t Jen’s idea of paradise. She could imagine it in the winter when the westerly gales came hurtling off the Atlantic, the place all draughts and mud. And wouldn’t that attract vermin? Mice? Rats even?

Another silence, only broken by laughter from the girls upstairs.

‘He’s full of principles, which is great if you’re minted, but not so easy for the rest of us.’

‘You’re thinking of the tea shop idea?’

‘Well yeah, but there are other things too, which get under John’s skin. It makes for a tense situation, and John’s not the best at coping with stress. Frank’s passionate about animal welfare and the whole organic thing. We are too, but there needs to be some flexibility. It’s as if he actually wants to lose money on the venture. We can’t have that sort of attitude. We’ve got the girls to think about and this new little one.’ She patted her belly.

‘Is Mr Ley a relative of yours?’

‘His mum was my gran’s sister. I called her Aunty Nancy. I visited the farm when I was a kid. Frank was already working in London then and the place was falling apart. His dad died not long after the crash and Frank came along with all that money to bring it back to life.’ She paused. ‘Nancy only died a few years ago. She was in her nineties, still sparky, still active. She had a heart attack after a day of gardening and died in her own bed. Frank was devastated, but I know that would have been how she’d want to go. That was when I took on the role of housekeeper, as well as working in the dairy.’

‘You must be knackered, with the kids to look after too.’

Sarah gave a little grin. ‘Yep, that’s my world. Permanently knackered.’ She didn’t seem thrown by it, though.

‘What does your husband make of it all?’

Another silence. ‘John finds it tricky,’ Sarah said at last. ‘He’d rather we were more independent, able to do our own thing. He doesn’t have an arty bone in his body, so the whole set-up here—Wes treating the place like a commune and bringing his mates to stay, impromptu gigs in the yard when we’re trying to sleep—that’s not really his bag. Like I said, he’s not good with stress.’

‘And you? Is it your bag?’

‘Honestly? It is really. I love the buzz and the company. I’m not sure how I’d cope doing the traditional wife thing, miles from anywhere in a hill farm on the edge of Exmoor. And that’s John’s dream.’

Jen thought about that. She could see how that might cause problems for the couple. She’d be with Sarah every time.

Before she could speak, the woman continued. ‘I’d give it a go, though. Only fair. We’ve done my thing since we moved here and now we’re saving like fury to find our own place. That’s why the tea shop is so important.’

Jen nodded to show she understood. ‘How well did you both know Nigel?’

‘I lived in the same street as Eve when I was growing up. I was a few years older but she was brighter and we were best mates, in and out of each other’s houses. Both only children. So I’ve known Nigel since I was a kid. He still lives in the same house in Barnstaple. John met him a few times when we first married—he came to our wedding—but only really got to know him when we moved in here.’ For the first time, Sarah seemed to notice the food left on the table. She pulled herself to her feet and began, haphazardly, to move plates towards the sink. ‘In a way they were very similar. Both quiet men. Both competent. No need to show off. None of that macho crap. They liked each other. John might not show it, but he’s upset.’ She turned to face Jen. ‘I loved Nigel. He was like a second father. When I was growing up, I could tell him stuff that I could never tell my parents. Just find out what happened. For Eve and for us.’

No pressure, then. Jen nodded and got to her feet.

Chapter Eight

IT WAS LATE AFTERNOON AND Matthew ordered Jen and Ross back to Barnstaple. ‘Get something to eat, then make notes of initial witness responses to share with the team. Ross, please could you do an internet search of all the residents at the farm. Any criminal convictions? And let’s see if we can have a first report on our victim’s phone records. Eve has given us the details of his mobile provider. Jen, any social media activity or news reports around Dr Yeo? His work could sometimes have been controversial, occasionally high profile if he’d started taking on his former employers in the health trust. We’ll clear out of the way at Westacombe now, and leave the place free for the CSIs and the search team.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members