Staying Fit

Chapter Thirteen

ON SUNDAY MORNING MATTHEW VENN WOKE early, as he always did. There remained the sense of unease that had nothing to do with the investigation. He’d always found work easier, certainly less complicated, than the personal baggage which weighed him down. This was his mother’s birthday and she would soon be sitting at their long kitchen table eating Sunday lunch. He still couldn’t quite believe her change of heart and wasn’t sure if he’d be hurt or relieved if she called the meeting off at the last minute, making some excuse about a sick sister or brother. Not talking about a relative, but a member of the Brethren, the community into which he’d been born.

By the time he’d showered and dressed, Jonathan was up too. There was music playing and Jonathan was singing along, loud and tunefully, and starting to pull out the ingredients he needed for the grand birthday cake. A rib of beef had already been taken from the fridge and would cook slowly, Matthew was told, until it melted in the mouth. Jonathan loved entertaining, everything about it, the preparation and the cooking, and the sitting down with friends. Matthew still couldn’t quite enjoy it, but he was starting to get there. Not with his mother, though; not with the crabby, anxious woman whose life was fixed with certainty, and who despised everything that her son had become.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

They had coffee and toast together, with the music still playing. Outside, the sun was shining, but they took that for granted. They’d all come to expect it now, the clear skies and the heatwave.

‘We could have lunch in the garden,’ Jonathan said. ‘I can set the table out there.’

‘Oh God, no! She’d hate it.’ As she’d hate anything adventurous and different.

‘Okay, in here then, but I’ll bring in flowers. Loads of flowers.’ Jonathan set down his coffee cup. ‘And give me a ring just as you’re about to pick her up. I’ll have everything ready.’ A pause. ‘You will be on time, won’t you? This is more important than work, for today at least.’

Matthew nodded. Now all this was started, he had to see it through to the end.

***

It was a relief to be on the road and heading to Barnstaple. The traffic wasn’t too heavy yet, and without needing the satnav he found the house where Helen Yeo had died and where Nigel Yeo had mourned her. It was a pleasantly proportioned house, substantial not grand. It backed onto the road out of the town, but was close to the shops and pubs of Newport, not far from Jen’s little terrace, a part of the community, not separate from it. There was a high wall to keep the traffic noise from the garden and Matthew struggled at first to find a way in. The entrance was from a side street and led into a shadowy garden, an oasis away from the town, with the muffled rumble of cars and lorries in the distance. Eve had given him a key. The crime scene team had been through the house, but hadn’t yet done a detailed search. They’d found no indication of violence there. It was clear that Yeo had been murdered where he was found.

Inside, it was cool. Matthew moved through the house to get a sense of the place before looking at it in any detail. This was a family home, but no longer lived in by a family. It was tidier than it would have been when Eve was a child; they already knew that Nigel had employed a cleaner, a woman who’d worked there for years, coming in on Thursday mornings for three hours, to clean the bathrooms and the kitchen, but there was none of the clutter that had probably been there when Nigel’s wife was alive and when Eve was still at home. One mug, rinsed and ready to go in the dishwasher, on the draining board in the kitchen. A pair of slippers carefully placed together close to the entrance to the hall. A copy of Friday’s Guardian, neatly folded on a coffee table in the living room, which looked out over the garden. There was a small television, the controls tidily arranged on the shelf beside it.

It seemed that when the illness had taken over Helen’s mind and her body, Yeo had moved her downstairs, to a pleasant little living room with a view of trees. The bed was still there, with its mattress cover and three pillows piled at one end. The nightstand had a cassette recorder on a shelf and a pile of audio books and music. Perhaps he couldn’t quite bring himself to clear the place.

Matthew wondered how he’d cope if Jonathan were suddenly ill, if he’d have Nigel Yeo’s dedication and patience to look after his husband this well. He hoped that he would. Then he thought ill health would probably hit his mother first. When he asked himself the same question about caring for her, he had no reply.

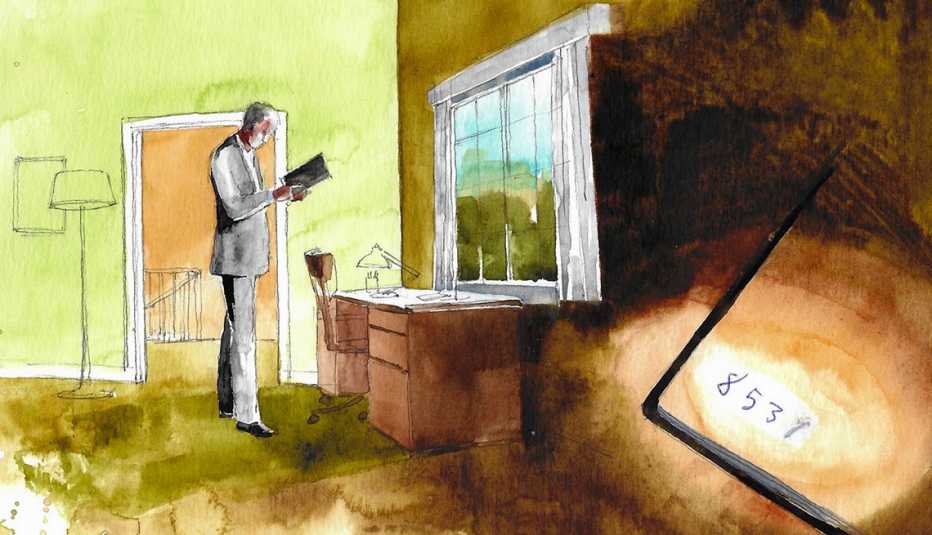

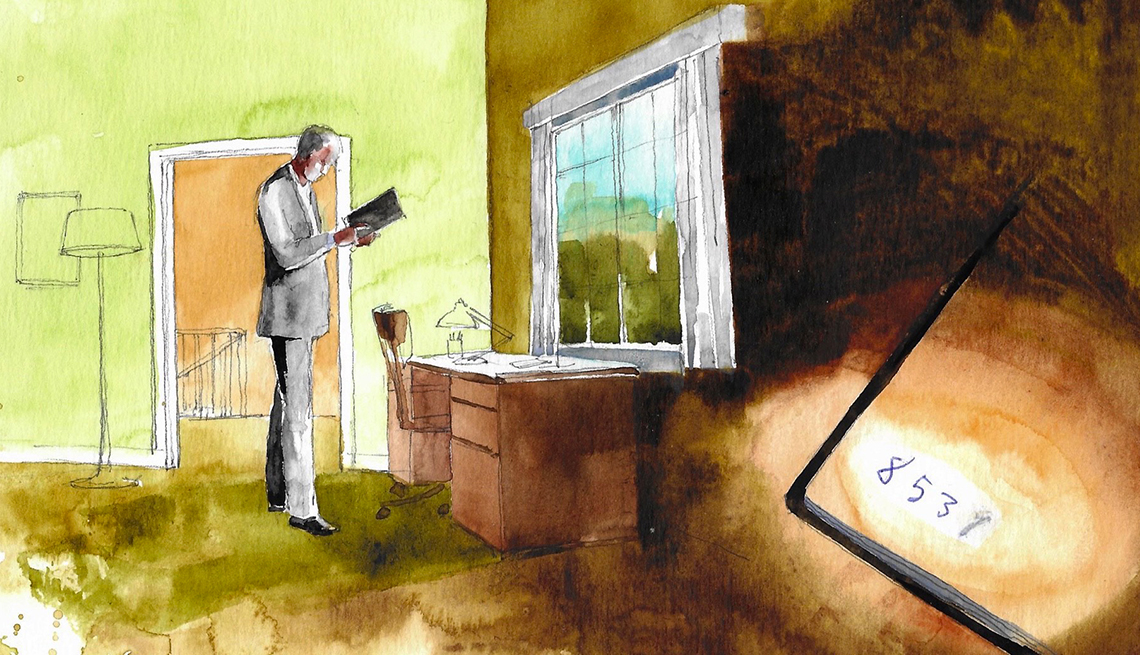

He moved upstairs and into Yeo’s study, which had been converted from the smallest bedroom. It faced the road and a row of smaller houses opposite. Matthew saw a gaggle of people going into the Baptist church on the other side of the road. He started opening drawers in the desk, not quite sure what he was looking for, and came across a large diary, with a page for every day. The diary contained both work and personal appointments. The writing was tidy, a little cramped. It seemed to Matthew that this was a man in control of his life.

He checked the entries for the week before Yeo’s death. There were a number of appointments marked. One said Team meeting. Beside it, he’d drawn a face with a down-turned mouth. It seemed he hadn’t been looking forward to that one. Others all seemed to be work-related: sessions with community groups and one with a social worker, a visit to a care home in a rural village.

On the Friday of Cynthia’s party, it seemed he’d had two meetings in the hospital. The first seemed more significant. Three names were listed, but one jumped out. Roger Prior. Matthew knew Cynthia Prior through court and this must be the husband who worked for the health trust. Another connection.

Further down the page there was another entry: Party (Jen Raff). This was another indication that he’d engineered an invitation to Cynthia’s gathering just to meet the detective. What a shame, Matthew thought, that Jen hadn’t spent more time with the man and listened to his concerns. But he knew Jen would already be thinking the same, would be haunted by guilt, and he didn’t intend to make her feel worse.

On the same page, hardly legible and scribbled at the last minute, it seemed, in different ink, Yeo had written a number: 8531. Or 8537. Matthew wasn’t quite sure. Some sort of reference or PIN? He put the diary in his briefcase and moved into the bedroom overlooking the garden, which Yeo must have once shared with his wife.

The room wasn’t at all what Matthew had been expecting. It had none of the bachelor austerity of the downstairs rooms, and was quite different in tone. There was a faint smell of fresh paint, and one wall was vivid red. A huge black and white photograph of a lighthouse with cliffs beyond hung there. The style seemed more Eve’s than Nigel’s and Matthew wondered if this had been the daughter’s attempt to cheer him up, to move him on from the period of grieving.

He then went into the attached bathroom. There were candles on a shelf near the bath. And on hooks on the door, two dressing gowns. Two electric toothbrushes over the sink. Perhaps Nigel Yeo hadn’t been the grieving widower everyone had thought him to be.

Matthew looked at his watch. It was still only ten thirty. He checked the number Ross May had provided for Lauren Miller and punched it into his phone. A woman answered and when he introduced himself, she said:

‘Of course. You want to talk about Nigel. I saw the news yesterday evening.’ The voice was ageless, pleasant, educated. ‘I live in Appledore.’ She gave him the address and the postcode. ‘I’ll be waiting for you.’

When Venn was a boy, Appledore had been known as a rough place, a centre for drug-dealing and teenage violence. It had the shipyard, as close to an industrial enterprise as anything in this part of the county. His mother had discouraged any social contact with the boys who lived in the town. Now the shipyard had closed and Appledore, at the mouth of the Torridge, North Devon’s second river, had transformed itself into an arty place of immaculately painted cottages along the narrow streets, artisan coffee shops and expensive restaurants. Former council houses on the edge of the town were now mostly in private ownership. There was an annual book festival and galleries exhibited local artists. Few locals could afford to buy properties here, and in the winter many of the houses—second homes and holiday lets—were empty. Matthew supposed it was an improvement, but on a sunny Sunday morning he knew it would be a nightmare to find somewhere to leave his car, and he felt some nostalgia for the past.

In the end, parking was no problem because Lauren lived a little out of the town, in a settlement of smart new houses. If she could afford to live here, with the landscaped gardens and the view over the Torridge to the estuary beyond, she hadn’t started working at NDPT for the money.

The house was minimalist, almost bare. Matthew couldn’t imagine children here. There was one enormous seascape on a white wall. Matthew found his gaze pulled into it; the wild sky and the space made him feel dizzy, vertiginous.

‘Brilliant, isn’t it?’ Lauren was standing behind him. She was almost as tall as he was, elegant, silver-haired. Not elderly, but not feeling the need to dye her hair to prove that she was still stylish. Perhaps because of the name, he’d been expecting somebody younger, and there’d been a moment of awkwardness when she’d opened the door to him. He hadn’t been quite sure that he’d found the right place. ‘I got it from a student’s degree show, when I was living in London, but the artist is Cornish. I think you can tell.’

‘When did you move here?’

‘Just over a year ago. I grew up in Bideford and was here until I went to university.’ She turned, gestured for him to take a seat on one of the sofas. ‘I came back because of my mother. She’s almost blind now. We live together. It’s not that she can’t manage on her own, but after my father died she became more isolated. She’d always been such a lively, companionable soul, and I couldn’t bear the thought of her being lonely. We sold her cottage in the town and moved in together.’ There was a pause. ‘But of course, I had selfish reasons for running home too. A messy divorce. We’d never had children and my share of the flat in Highgate easily bought me this place and gave me enough to live on until retirement.’

‘And yet you decided to go back to work?’

‘Ah, that was to keep me sane.’ Lauren smiled. ‘And because Nigel asked me to.’

‘You were friends?’ She didn’t respond at first. ‘Rather more than friends, I hope. In the last few months at least.’

‘You were lovers?’ Although he’d already suspected that there was more to the relationship, Matthew felt himself blushing. The puritan upbringing could come back to shock him when he was least expecting it.

‘Only recently. We’d been close friends for a while. Why are you so surprised, Inspector? Is it our age that makes it so unlikely?’

‘Eve didn’t mention a relationship,’ Matthew said. ‘I thought she would have done.’

‘Eve didn’t know. I’ve met her, but only a couple of times and then with other people. Nigel and I were very discreet and had decided to wait to go public. It would have been very tricky because of working together and Eve was so close to her mother. Besides ...’—she gave another sad smile—‘... there was something exciting about the secrecy. It made us feel young and foolish. Romantic. We wanted the chance to be selfish for a while. I hadn’t even told my mother.’ She looked directly at Matthew and he could tell how wretched she was.

‘How did you meet Nigel?’

‘It was at a dinner party at Frank Ley’s place, Westacombe. I’d worked with Frank briefly in London and I liked him. Perhaps we had things in common, coming from the same part of the country, not quite fitting in with the brash young money men. I sent him an email when I moved back down and he invited me along. We all sat round the table in his grand dining room: Frank, Eve, Nigel and another guy who worked there.’

‘Wesley Curnow?’

‘Yes. That’s right. I was sitting next to Nigel.’ She paused. ‘I remember everything about that night. It was a first step in moving on from my previous life. Nigel said that the woman at his work who looked after the accounts had taken early retirement. I volunteered to take over until they could employ someone.’

‘And you’re still there?’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members