AARP Hearing Center

COVID-19 Update: The Museum of African American History continues to operate with limited hours, and timed-entry tickets must be purchased in advance.

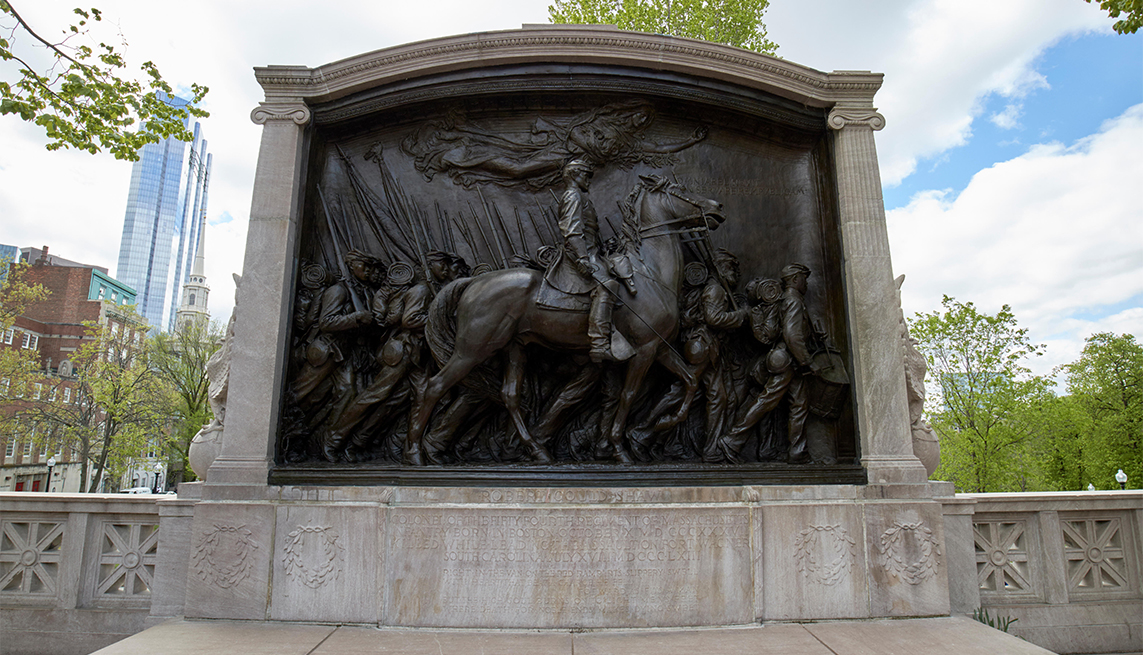

In a city as rich with history as Boston, the constant deluge of busts, equestrian statues, fountains, national landmarks, obelisks, plaques and victory columns can have an almost numbing effect. With this much history, it's easy for even the most noteworthy pieces to get lost in the shuffle. Case in point: The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, a stately bronze relief on the northern edge of Boston Common.

Although widely considered one of the country's most stirring war monuments, this 1897 memorial is easily missed by the thousands who stream past it every day. But stop and take a closer look. This emotionally resonant masterpiece by Beaux-Arts sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens is a testament to a game-changing historical figure. More than that, it was the nation's first public monument to honor African American soldiers.

Battle casualties

If you don't know Col. Shaw by name, you may know him by reputation: Matthew Broderick played “the blue-eyed child of fortune” in the 1989 Oscar-winning film Glory. Born to a prominent Boston family of abolitionists in 1837, Shaw, at the young age of 25, took command of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first all-Black regiments to fight for the Union in the Civil War. Unfortunately, he and more than half his regiment were shot and killed during the July 1863 Second Battle of Fort Wagner, near Charleston. In a sign of disrespect for Shaw having led Black soldiers, the commanding Confederate general refused to return his body and instead had it buried in a mass grave alongside his men. But the general's move had the opposite effect: His family saw the burial as a great honor, and his father wrote, “We can imagine no holier place than that in which he lies, among his brave and devoted followers, nor wish for him better company — what a body-guard he has!"

After his death, veterans from the 54th Regiment proposed a monument to Shaw's memory near his burial site, but local citizens stopped it from being built. Instead, the funds raised for its construction went toward building Charleston's first free school for Black children in Shaw's name. Later, thanks to the efforts of African American businessman Joshua B. Smith (who had once worked for the Shaw family), a committee convened in Boston to plan for a proper memorial — a committee that included Charles Sumner, the senator famously beaten nearly to death by a pro-slavery representative after a fiery abolitionist speech.

To create the memorial, the committee commissioned Saint-Gaudens, who crafted some of the most gorgeous sculptures of the day, including “Abraham Lincoln: The Man” (1887) in Chicago's Lincoln Park. The sculptor drew inspiration from a French painting of Napoleon on horseback in front of rows of marching infantry men to depict a similar scene: Shaw and the 54th Regiment marching down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863, before shipping out to Charleston.

Plan Your Trip

Location: Look for the Shaw memorial at the northeast corner of Boston Common, directly across from the Massachusetts State House, near the intersection of Beacon and Park streets

Getting there: The memorial is a two-minute walk from the MBTA's Park Street transit station, which serves the Red and Green Lines, and a five-minute walk from the Bowdoin station, which serves the Blue Line. If you're arriving by car, the Boston Common underground parking garage is a bit pricey ($12 for up to an hour on weekdays), with a slight discount for evenings and weekends.

Hours: The restored memorial is viewable 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but most of the other stops on the Black Heritage Trail (BHT) are now private residences you can only see from the outside. The exception is the Museum of African American History (MAAH), open Monday-Friday (closed Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year's Day), 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Admission: There's no fee to view the memorial; the only portion of the BHT that requires paid tickets is the MAAH ($10, free for those 62 and older).

Best season to visit: From Memorial Day through Labor Day, National Park Service rangers lead free BHT walking tours, departing from the memorial at 1 p.m. daily, with an additional tour at 10 a.m. from July Fourth through Labor Day.

Best time to visit: During summer, join the morning tour so you have ample time to explore the MAAH at trail's end.

Accessibility: The BHT is wheelchair accessible, but the 1.6-mile path involves occasional uneven sidewalks and steep hills. The MAAH is fully accessible for wheelchair users but has no wheelchairs available on-site.

Ever a perfectionist, Saint-Gaudens took his time getting every detail right. “It took Saint-Gaudens nearly 14 years to complete the monument, much to the chagrin of the committee,” says Shawn P. Quigley, a park guide with the National Parks of Boston. “In fact, one committee member complained in 1894 that ‘that bronze is wanted pretty damned quick! People are grumbling for it, the city howling for it, and most of the committee have become toothless waiting for it!'"

Massive masterpiece

At 11 feet by 14 feet, the massive bronze relief depicts a row of lifelike soldiers marching with their bedrolls, canteens, drums and rifles, led by a stoic Shaw on horseback. An ethereal female allegorical figure floating above the gritty realism below carries an olive branch for peace and an armful of poppies, symbolizing death. Note that it wasn't until 1982 that the Friends of the Public Garden raised funds to restore the monument and finally inscribed the names of the fallen Black soldiers who died alongside Shaw.

"One thing I always like to call attention to are the individual faces of the soldiers,” says Quigley. “It's a masterpiece when you look at the entire monument, but the painstaking detail is where I think the genius of Saint-Gaudens really shines."