AARP Hearing Center

CLOSE ×

Search

Popular Searches

Suggested Links

CLOSE ×

Search

Popular Searches

Suggested Links

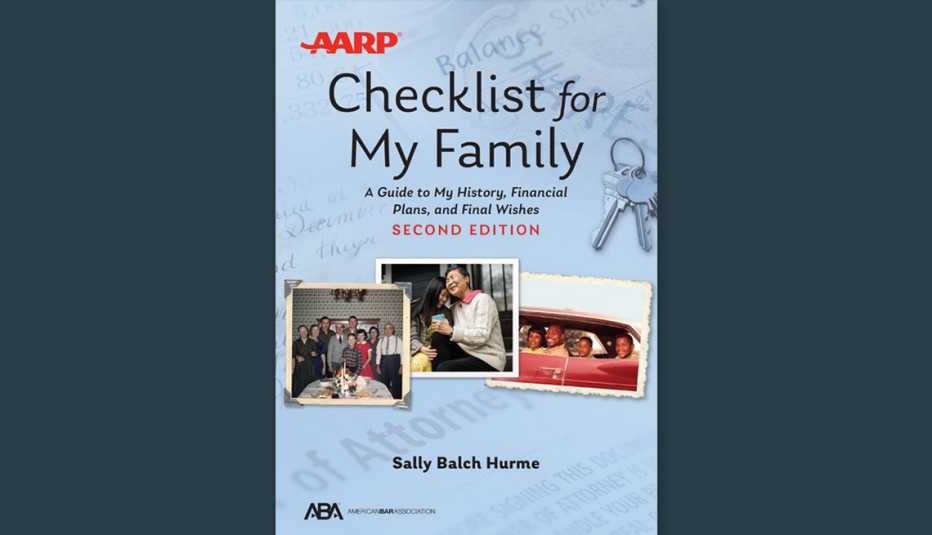

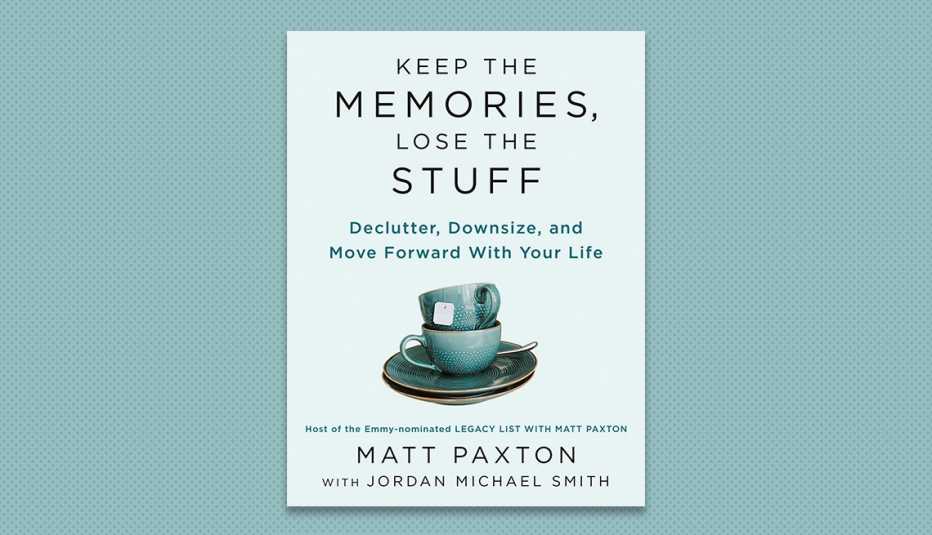

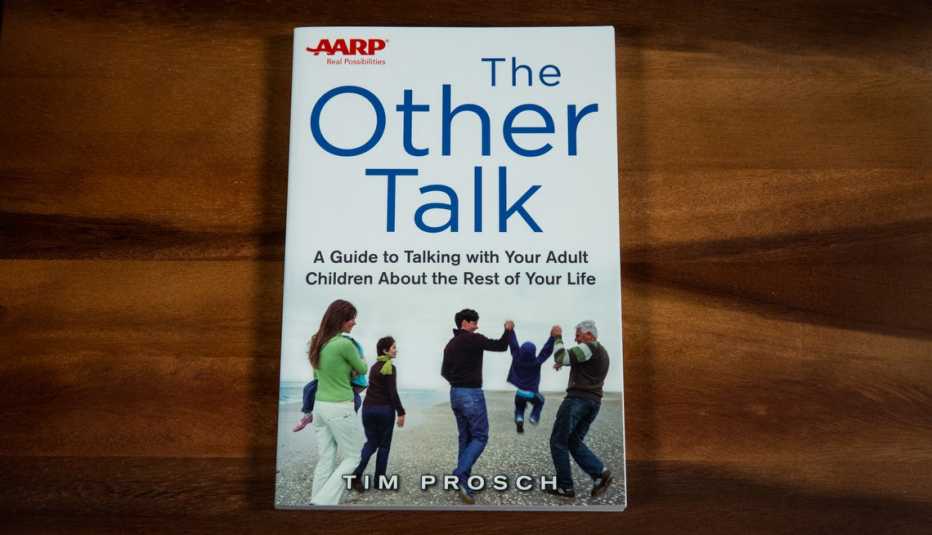

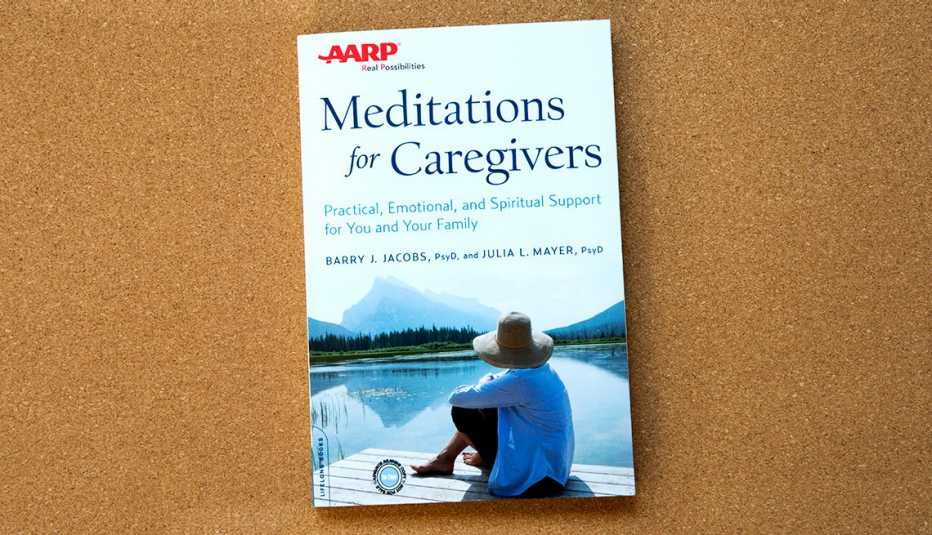

AARP Bookstore

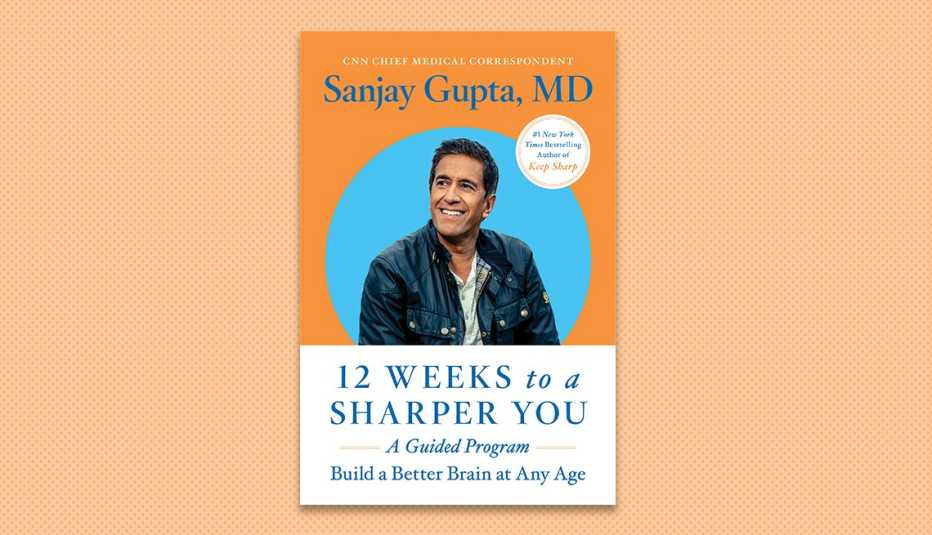

AARP has published books on a range of issues. Find e-books, print books and free downloads on health, food, technology, money and work, home, family and caregiving, and more.

New from AARP Books

Bestsellers and Award Winners

Living Now Book Award Gold Medalist

Answers to the 7 Big Questions of Midlife and Beyond

Explore hundreds of AARP benefits, including a wide range of discounts, programs and services.