Staying Fit

It’s a classic example of a simple thing gone crazy. In recent years countless financial experts have advised Americans to consider index funds — baskets of stocks or bonds that track the companies or investments that comprise market indexes — as a straightforward, low-cost, lower-risk way to invest without having to depend on a fund manager’s luck or skill in picking winners.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

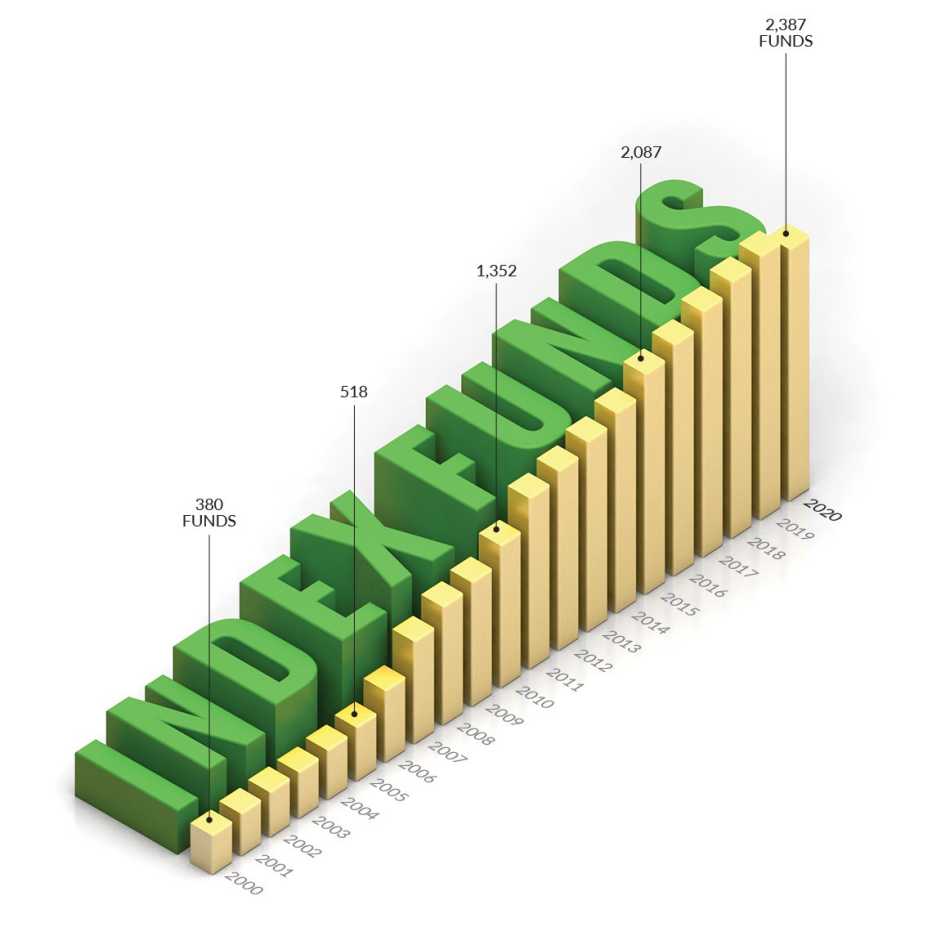

So what happened? A massive proliferation of index funds.

Consider that there are 2,400 companies trading on the New York Stock Exchange and 2,500 U.S. index funds at latest count, according to the investment research firm Morningstar (some 60 funds tracking the popular S&P 500 stock index alone!). And although funds once focused on major indexes, such as those meant to represent all U.S. stocks or all non-U.S. stocks, hundreds of funds are now tracking narrow and sometimes obscure sections of the market, like natural gas distributors or water industry companies.

“Indexing has gone from evolution to pollution,” says Rick Ferri, an investment adviser at Texas-based Ferri Investment Solutions. “Now everything has become an index.”

Compounding the confusion: Traditional index funds are “passive,” meaning that they don’t require the active daily management by a professional stock picker. (“Passive” may sound weak, but it isn’t; index funds have typically beaten the investment performance of most professional money managers while generally charging lower prices.) But now pros blur the lines by devising indexes, then launching funds that track the indexes they have helped create. They are dressing active strategies in index-fund clothing.

Given so many options and so little clarity, how do you pick the right fund or funds?

Look for breadth

Lower your investment risk by buying funds that represent broad slices of the market, not narrow ones. An S&P 500 index fund, for example, contains stock shares of 500 of the largest publicly traded companies in the U.S. Other stock indexes cast even wider nets: You can buy a total U.S. stock market index fund, which gives you exposure to companies both big and small in a variety of industries, or even a total world stock market fund.