Staying Fit

On Nov. 5, 1966, Captain Robert Foley, 25, led a company assault on enemy machine gun positions in Quan Dau Tieng, Vietnam.

Pinned down by enemy fire and with both his radio operators hit, he grabbed a machine gun and charged the enemy, shouting orders and rallying his men.

You can subscribe here to AARP Veteran Report, a free e-newsletter published twice a month. If you have feedback or a story idea then please contact us here.

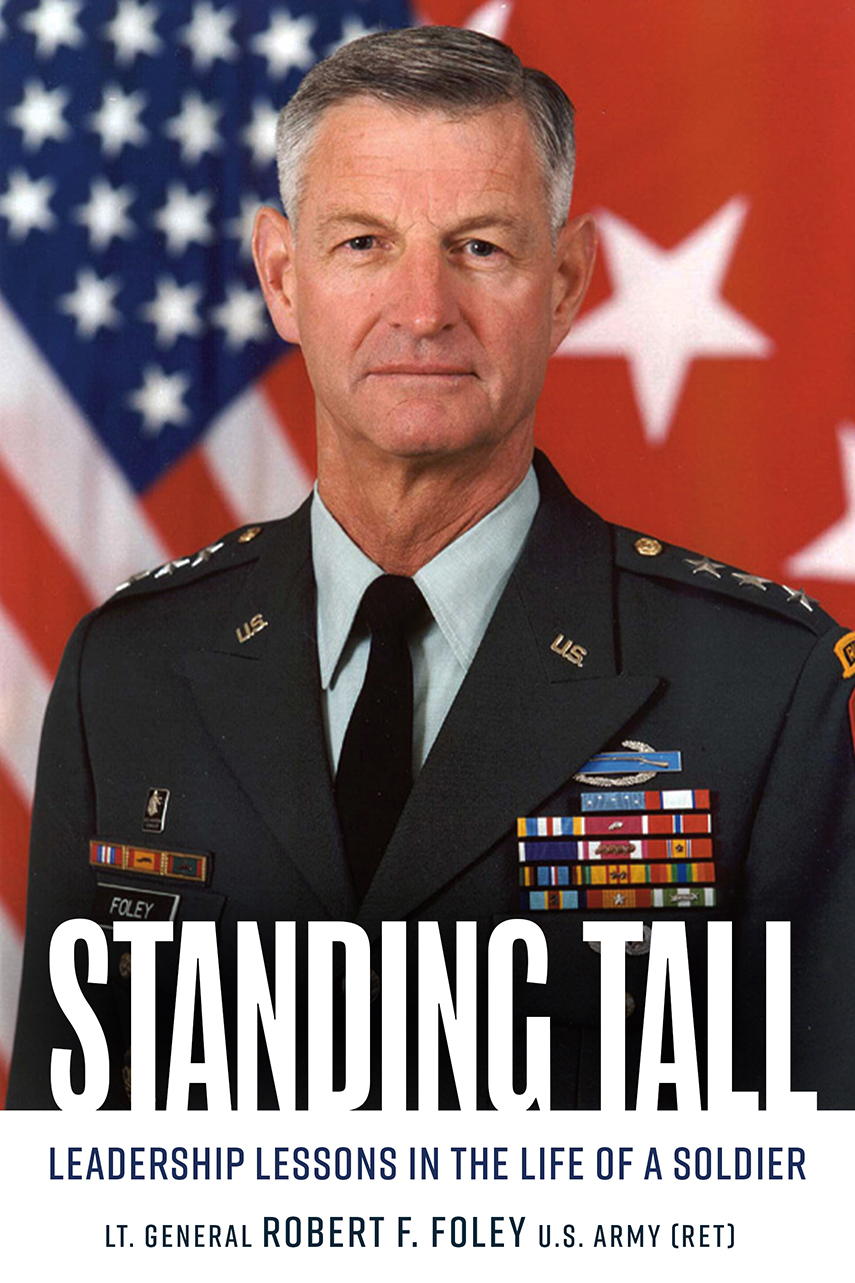

Foley was wounded by a grenade, but the assault succeeded. He was awarded the Medal of Honor and went to on reach the rank of lieutenant general in a 37-year career.

Now 81, Foley — who was 6 feet 7 inches and had chosen the Army over a college basketball scholarship — is the author of Standing Tall: Leadership Lessons in the Life of a Soldier.

AARP Veteran Report asked him for seven leadership lessons. You may not still be serving, but here are some lessons you can apply to everyday life:

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

1. Develop moral courage

The ability to do the right thing is paramount. Respect and courtesy is one aspect, but Aristotle was correct when he wrote that character is a habit, the daily choice of right over wrong.

Basing decision-making on values is vital yet more difficult when you deal with more complex issues. Begin by recognizing the existence of a dilemma and then determine a course of action, even if it is unpopular.

If you get an order to do something that is wrong or won’t work, you need the moral courage to say so. In the military, you are dealing with matters of life and death. Doing the right thing is not always easy in the short term, but it works in the long term.

2. Lead by example

Sergeant Major of the Army Julius W. Gates once told me: “Be visible and be accessible”. Soldiers want to see you. Join them for lunch in the dining facility, sit in a muddy foxhole with them, run by their side on a misty early morning.

More From AARP

The Best Sports and Recreation Discounts for Veterans

Whether you’re taking part or watching, there are great military deals to be foundMY HERO: When My Husband Was Killed, His Father Saved Me

A Marine father’s solemn duty was to support the widow of his beloved Green Beret sonGary Sinise Salutes Post-9/11 Veterans

America’s War on Terror began 22 years ago. A new generation of heroes has led the wayWorld War II Veteran is Writing Children's Books at 101

Marine who served in the South Pacific and space program has a message for kids everywhere about learning