Staying Fit

Even after two decades of researching and writing about our Vietnam prisoners of war, the sentiments expressed by one of them was still a surprise.

“What folks do not realize is that during the Vietnam War, the wives and families had it far worse than we did,” said Dick Stratton, a retired Navy captain who is now 91.

“Our families from one day to the next did not know if we were okay or not; they had no confidence that our government gave a damn about us or would ever bring us home.”

You can subscribe here to AARP Veteran Report, a free e-newsletter published twice a month. If you have feedback or a story idea then please contact us here.

He was right. That was 2015, and a book about his wife and the other family members who advocated for the American captives, still the longest-held group of POWs in our nation’s history, was long overdue.

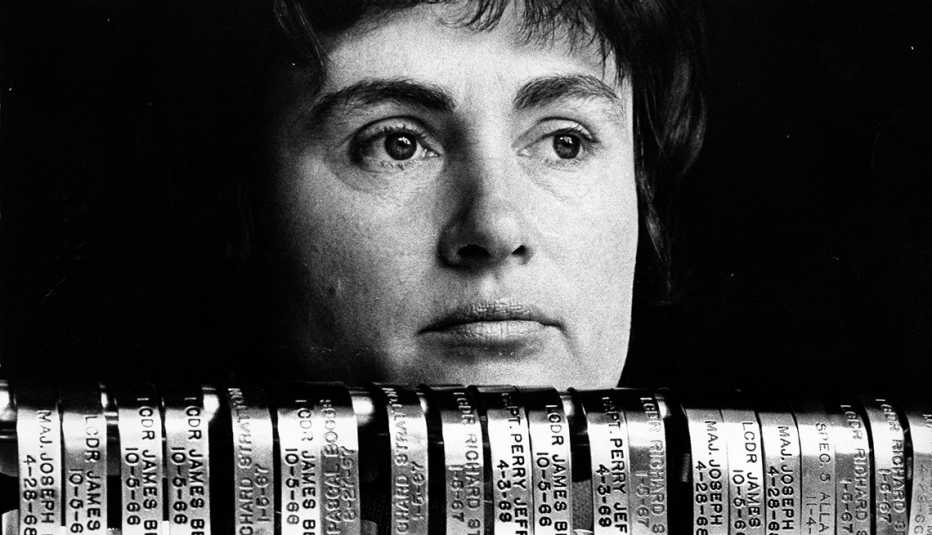

Lt. Cdr. Dick Stratton was captured in January 1967 when his A-4 Skyhawk was shot down. At first, his wife was afraid to speak out, having been admonished to keep quiet when he went missing. But she suspected he was enduring torture, malnutrition and isolation at the Hanoi Hilton.

A clinical social worker, she had three sons under 6 years old when her husband was incarcerated.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Wobbly kneed, Alice gave her first speech in October 1969 to an empathetic audience at her church in Palo Alto, California. Next, she spoke in front of a like-minded group: military wives. Each time it got easier. She read her speech to anyone in the Bay Area who would listen: Kiwanis and Rotary Clubs, schools, colleges and service organizations.

To keep her emotions in check and appear calm, her delivery was a bit flat. Yet her underlying passion captivated audiences. A Toastmaster advisor smiled, shaking his head. “I don’t understand it, but that monotone is still effective.”

Encouraged by other wives, she initiated letter-writing campaigns to the foreign minister of North Vietnam, American newspaper editors and legislators. She went public for her husband, her children and the other POWs, revealing the inhumane treatment Dick and his comrades were being subjected to by the North Vietnamese.

Once shy, Alice morphed into a crusader and lobbyist, participating in press conferences, collaborating with other wives on marketing campaigns. Though none of these skills came easily, her persistence paid off.

More From AARP Veteran Report

Understanding Health Care Benefits for Veterans

Everything you need to know about VA and insurance coverage as a civilianMY HERO: Sister Sets Out to Find Brother's Comrades

Vic Best died bravely in 1967. Now, his sister is giving back to veterans.5 Secrets for Veteran Starting Their Own Business

Pro tips that will set you up for success as an entrepreneur8 New Military Museums That Will Honor Veterans

Exciting plans for new opportunities to learn about military skill and sacrifice in U.S. history