Staying Fit

It’s been nearly two years since COVID-19 turned life as we knew it upside down, sending rates of depression and anxiety soaring. Then in November, just when many people began to feel that the pandemic was easing, the wildly infectious omicron strain brought new fears of illness, as well as despair: Will this thing ever end?

“Our brains are not designed to live under chronic stress,” says Karen Hahn, 54, a social worker in Washington, D.C., who says she has upped her dosage of antidepressants in recent weeks to try to lift herself out of a self-defeating depression-inertia loop worsened by omicron. “I’m laying on the couch napping all day Saturday going, ‘Yeah, if I could just put my tennis shoes on and go outside and walk for an hour I’d feel better.’ But I can’t even do that. I just want to nap.”

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

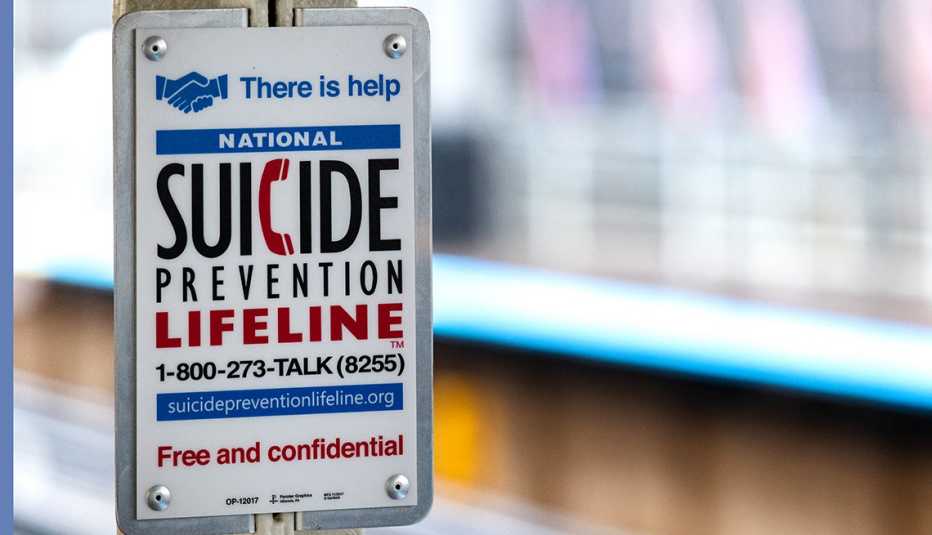

Americans’ mental health needs during the pandemic already began raising alarms months ago. Last year, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) HelpLine (see box below), which offers support for mental health and substance abuse issues, received 1,027,381 calls. That’s up 23 percent from 2020 — when call volume was up 27 percent over 2019.

But the emotional strain has grown more acute in recent months, health experts say. Texas’ statewide mental health COVID support line, for example, has seen a 20 percent increase in calls since early December, says Greg Hansch, a social worker and executive director of the Texas chapter of NAMI.

While part of that uptick in calls for help was driven by the stress of the holiday season, he notes, it’s also related to “the uncertainty of the omicron variant.” Anxiety is often stoked by uncertainty, says Hansch, who believes that the pandemic’s general unpredictability “has been a big driver of a lot of the mental health concerns of the last few years.”

He also cites older people’s genuine anxiety about getting sick, since they’re more likely to suffer negative effects from a COVID-19 infection, as well as grief, with so many lives lost and experiences missed (weddings, grandchildren’s births). There’s also “guilt and shame, for people who do contract COVID-19 feeling like they’ve failed in some way,” he adds.

As we near the start of the pandemic’s third year (it officially began on March 11, 2020, based on the World Health Organization’s declaration), nerves are more frayed than ever, says Katherine Gold, M.D., an associate professor in family medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School and a primary care physician. “We’re absolutely seeing just exhaustion from the pandemic,” she reports. “People are tired of isolating and tired of all the restrictions and just tired of the fear of getting COVID — not only patients with existing mental health conditions, but people who don't really have a diagnosis of a mental health condition are feeling increasingly isolated, or anxious.”

She and other experts say the persistent pandemic is responsible for exacerbating two particularly big risk factors for mental health issues:

Isolation

Reza Hosseini Ghomi, M.D., a geriatric neuropsychiatrist in Billings, Montana, says he’s seeing more depression and anxiety among his older patients, sometimes as a result of the loneliness that can come with isolation. It “manifests typically as either anxiety or depression. [There’s] a lot of sadness, hopelessness, ‘Oh, this is never going to end.’ And a lot of sleep issues.”

Loneliness can worsen our health on many levels; it rivals smoking for its negative impact, and raises the risk of dementia by 50 percent, according to a 2020 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.