AARP Hearing Center

About Vaccines

- What is a vaccine?

- How do vaccines work?

- What happens when you get a vaccine?

- How does your body fight back?

- Why can you feel side effects?

- Why do some vaccines last longer than others?

- What is herd immunity?

There’s a lot of noise out there about vaccines. News headlines, social media posts and even conversations with friends can make it difficult to know what’s true and what isn’t.

Maybe you’ve heard that vaccines can “overwhelm” the immune system. Or that vaccines “don’t work” because some people still get sick after a shot. With so much misinformation, it’s no wonder people feel uncertain.

The science, though, is clear. Vaccines are safe, effective and the most powerful tool we have to protect ourselves from getting sick, says Dr. Robert Hopkins, medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and a professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

They are especially crucial for older adults, who are at higher risk from illnesses like influenza, COVID-19, RSV and pneumonia.

Vaccines have saved millions of lives — and continue to do so every year.

“When there’s a huge volume of information out there that’s not correct, it’s hard oftentimes for people to filter through that and find the truth,” Hopkins says. “We are in a particularly challenging situation because there are news pundits … that are putting out information that is blatantly false, that is scaring people. It’s causing people not to get vaccinated and will cost lives.”

Here, public health experts share the basics about what happens in your body when you get a vaccine to help clear up confusion and hopefully offer some peace of mind.

What is a vaccine?

A vaccine is a medical treatment that helps your body defend itself against disease, says Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

All vaccines work basically the same way: They introduce a harmless component into your body that “trains” your immune system to recognize and respond to potential invaders such as viruses, bacteria or other pathogens.

“Because it’s trained, it’s much more effective at fighting off that infection after you get exposed,” Schaffner says.

Some vaccines prevent infections entirely. Others reduce your risk of having severe disease that can lead to complications, hospitalization or death. Some also reduce your risk of transmitting the disease to others.

How do vaccines work?

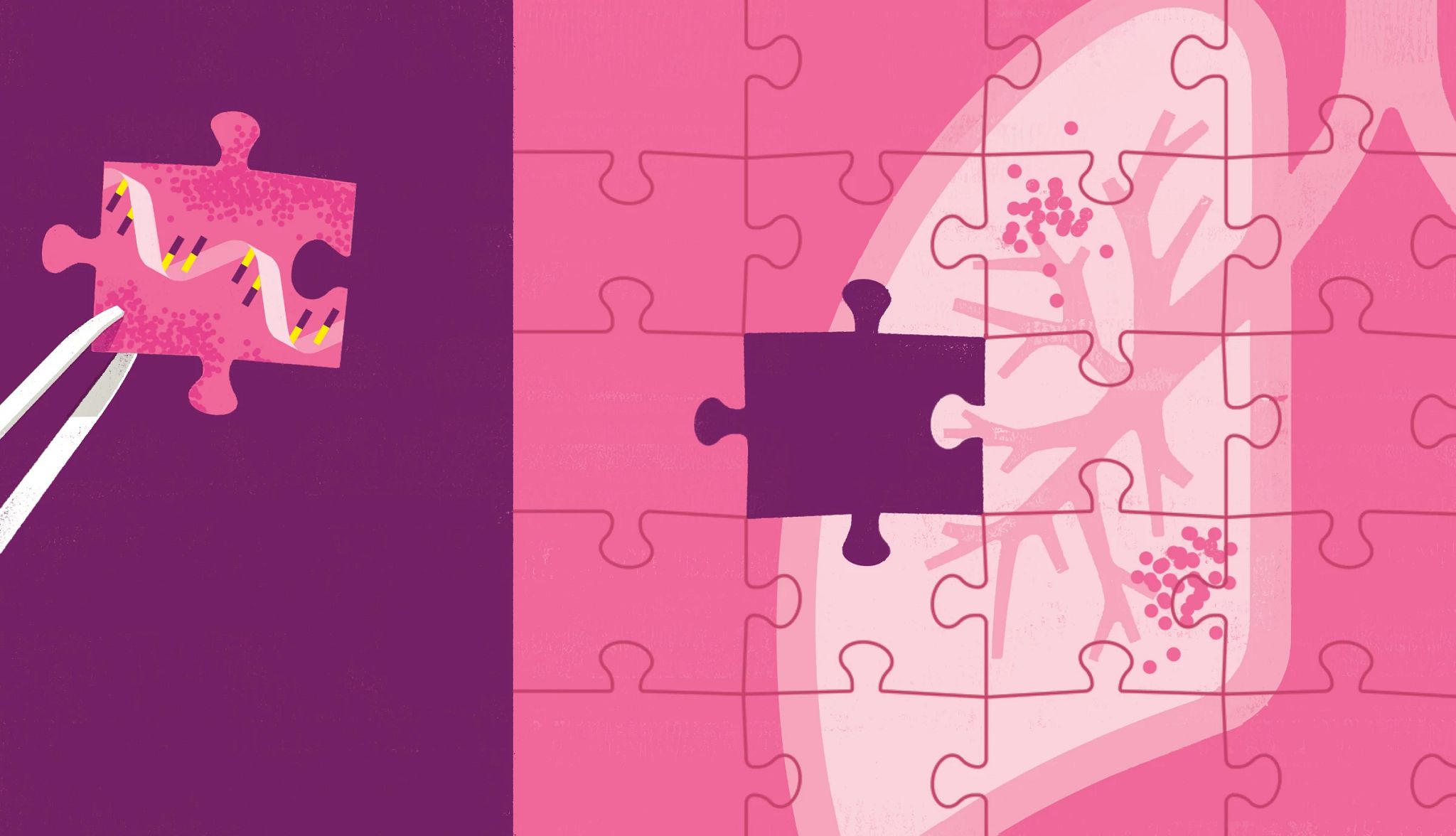

Every infection has a telltale feature, called an antigen, that the body can spot as foreign, says Dr. Paul Thottingal, an infectious disease specialist and senior medical director for communicable diseases at Kaiser Permanente in Seattle.

An antigen is the identifier or “fingerprint” of a germ, he explains.

Vaccines introduce an ingredient that mimics that fingerprint, giving your immune system a chance to learn how to fight the germ. Different types of vaccines use different methods to do this.

))

))

)

)

More From AARP

10 Ways to Avoid Getting the Flu

Common-sense things to do to avoid infection.

11 Health Problems That Can Cause Brain Fog

When thinking is unclear, unfocused or slow, you need answers

Smart Guide to Vaccines for Adults Over 50

A comprehensive guide to vaccines and their benefits