AARP Purpose Prize Honorees

En español | You live. You learn. You give back. No one knows this better than people ages 50 and older, who have spent decades accumulating a wealth of knowledge that only life experience can bring. Armed with this wisdom, they are a powerhouse of innovation tackling some of the greatest societal challenges of our time and inspiring others to do the same.

The AARP® Purpose Prize® award supports AARP's mission by honoring extraordinary people ages 50 and older who tap into the power of life experience to build a better future for us all.

“Our Purpose Prize honorees are shining examples of a simple, yet profound truth: When we find our sense of purpose — that certain something that gives us a reason to get up and get going every day — we not only give meaning to our own lives, we make the world a better place for everyone,” said AARP CEO Jo Ann Jenkins.

AARP Purpose Prize winners receive $50,000 for their founded nonprofits and a year of technical support to help broaden the scope of their organization’s work. Examples of current supports include one-on-one leadership coaching for founders, data and evaluation consulting, succession planning, prospectus development, social media and branding support, and more.

The call for applications for the next AARP Purpose Prize award is open until February 29, 2024. Learn more here.

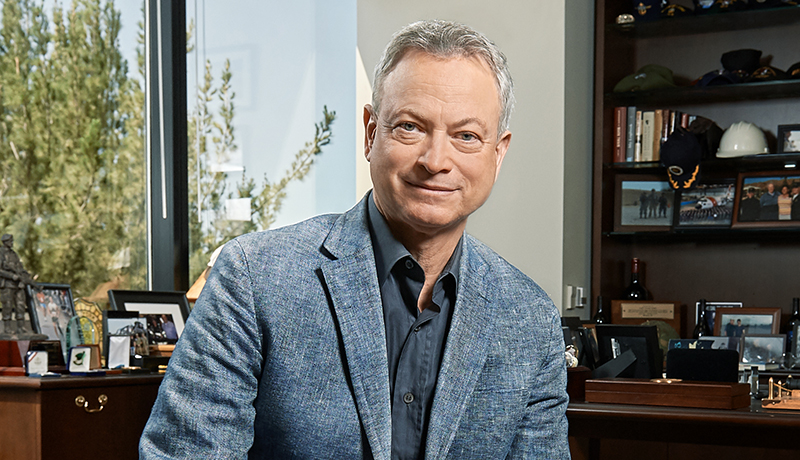

Honorary Award

AARP is presenting award-winning actor and humanitarian Gary Sinise with an honorary Purpose Prize Award for his founding and leadership of the Gary Sinise Foundation. Founded in 2011, the Gary Sinise Foundation honors military members, veterans, first responders, their families, and those in need. It creates and supports unique programs designed to entertain, educate, inspire, strengthen, and build communities. The Foundation’s initiatives include building mortgage free, specially adapted homes for severely wounded veterans and first responders, uplifting military members and families through entertainment, mental wellness programs, and financial support in times of urgent need.