AARP Hearing Center

Nothing about choirs is harmonious with COVID-19.

Group singing, which generates respiratory droplets at high rates in close quarters, dramatically increases chances of COVID spread. Linked to multiple outbreaks, choirs have been silenced in most places.

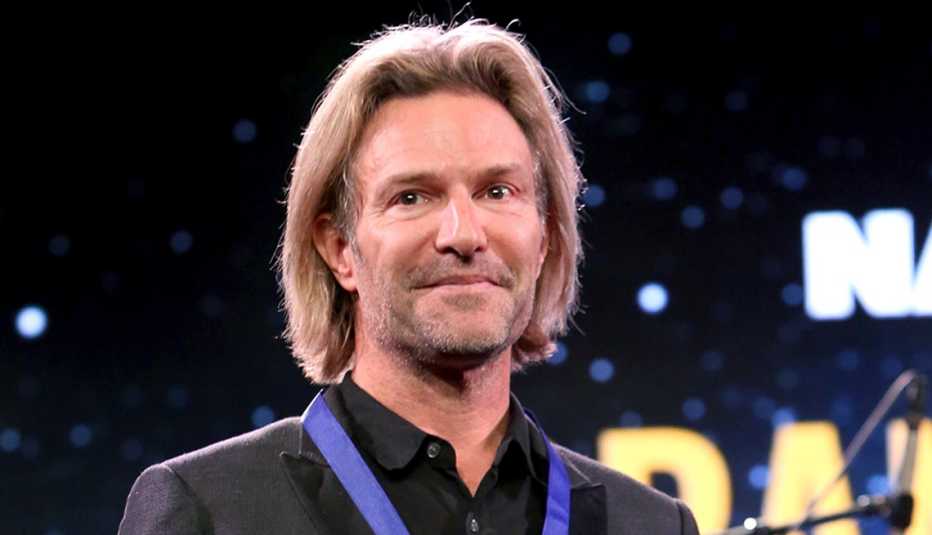

But that didn’t stop conductor and composer Eric Whitacre from assembling the largest choir in history to perform his new piece “Sing Gently.” The 17,572 singers were socially distanced online. Each had submitted videotaped vocals to Whitacre, who painstakingly stitched them into a massive online chorus, viewed so far by 1.4 million on YouTube.

Whitacre, a Nevada native and Juilliard School of Music graduate, has filled prestigious venues conducting orchestras around the world and won a Grammy for his 2011 Light and Gold album of choral works. He didn’t expect to become an internet choir wizard.

“I played synthesizer in high school,” says Whitacre, 50. “I played in a pop band. One day, the choir director invited me to sing. On the first day, I sang Requiem by Mozart, and that was it. My life was completely changed. I became the world’s biggest choir geek.”

Virtual choirs before a pandemic

After unlocking the technical challenges to constructing virtual choirs in 2009, Whitacre began experimenting and producing giant cyberspace sing-alongs, building a reputation as a pioneer in the field. His first, 2010’s “Virtual Choir 1: Lux Aurumque,” included 185 singers from 12 countries. In 2013, Whitacre partnered with Disney to produce a virtual choir of 1,473 singers from all 50 states singing his Christmas song “Glow” for the World of Color: Winter Dreams show, which premiered at Disney’s California Adventure Park. He teamed with UNICEF for his Virtual Youth Choir featuring 2,292 young singers from 80 countries. It made its debut at the opening ceremony of the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games.

“The first one, which I didn’t think anyone would see, went viral and got picked up by international news media,” Whitacre says. “People started writing me, ‘When will be the next one? I have to be a part of it.” Each one gets bigger and grander. We don’t try to make them bigger. If anything, we reduce the length of time we accept videos.”

A stellar collaboration — with NASA

The Hubble Space Telescope inspired his 2018 “Deep Field” composition for symphony orchestra and chorus and led to a collaboration with NASA to create Deep Field: The Impossible Magnitude of our Universe, a film of stunning imagery captured by the telescope. The accompanying virtual choir features the Eric Whitacre Singers, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and 8,000 singers ages 4 to 87 representing 120 countries.

More on Entertainment

With Choirs Restricted, Singers Raise Their Voices Online

How choruses have gone digital in the COVID-19 eraPandemic Songs: The New Music Genre

Songwriters draw inspiration from the timesHis Music Lifts Up Nursing Home Residents, Even During COVID-19

Michael Krieger streams his shows into the places he once played