AARP Hearing Center

EDITOR’S NOTE: Emma Heming Willis could not understand why her marriage to actor Bruce Willis seemed to be fraying, but they had more and more miscommunications: He often remembered conversations differently from her, for instance. “Sometimes I’d think, Is he for real? Is he pretending? Or am I going crazy?” she recalls in her new memoir and caregiving guide, The Unexpected Journey: Finding Strength, Hope, and Yourself on the Caregiving Path (September 9). Finally, in 2022, Bruce, now 70, was diagnosed with aphasia — a communication disorder that affects a person’s ability to process and express language — and later that year with frontotemporal dementia, or FTD.

Heming Willis, 47, also offers a road map for others new to caregiving, covering self-care (including focusing on one’s own brain health), parenting, bringing in help and the importance of reframing the journey to include as many positives as possible. What follows is adapted from The Unexpected Journey.

(You can also read AARP's interview with Heming Willis and what we learned from the book here.

When I suspected something was “off” with Bruce but couldn’t put my finger on what it was, I went through every possible explanation in my head. Was there a problem in our marriage? Was it Bruce’s sleeping difficulties?

Maybe it was his hearing loss. In the ’90s when he was filming Die Hard, there was a scene where he had to fire a gun underneath a table. When it was shot, oddly, Bruce wasn’t wearing any protective earplugs or covering, and he lost a large percentage of his hearing in one ear. When we first got together, this never posed a real problem.

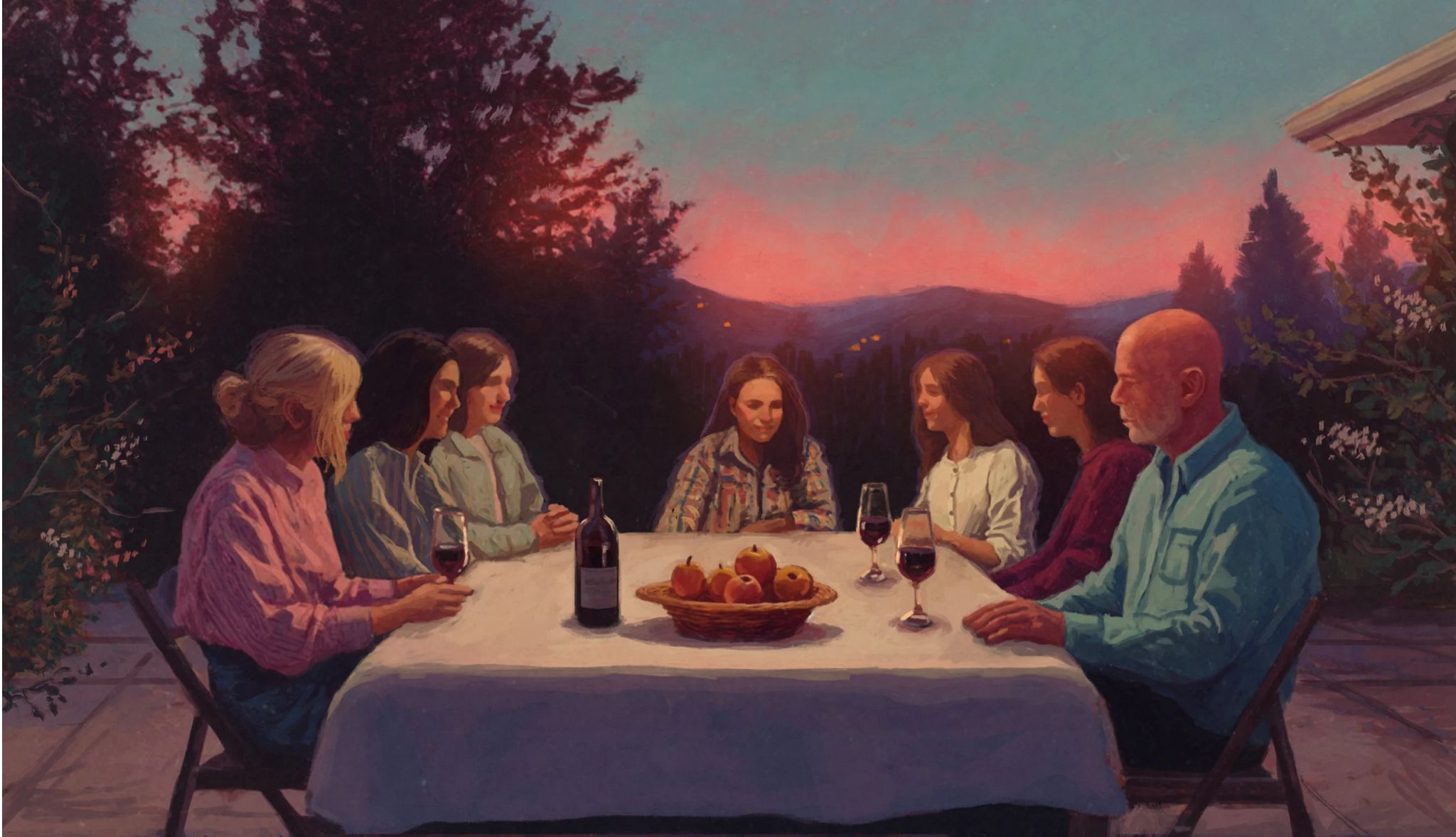

Years later, however, I began to notice him sort of check out if we were at a dinner party or meal with the entire family. He would sit back and let everyone else do the talking without contributing very much. Mind you, when we would get the family together, Bruce was usually the only man at a table full of women with me, our two girls, and his three older daughters speaking a mile a minute and over each other with excitement. Initially, I thought he was just letting us have our girl time to “yack it up,” as he would say, rather than try to get a word in. I assumed his hearing loss made it easier for him to melt into his seat with his hands clasped gently on his lap.

More From AARP

How to Be a Caregiver for Someone With Dementia

It’s a tough job, but there may be more help than you think

The Unique Challenges of Dementia Caregiving

Tips on how to manage such often-difficult care

Understanding Loved Ones With Dementia

Communicating with loved ones with dementia using strategic methods