AARP Hearing Center

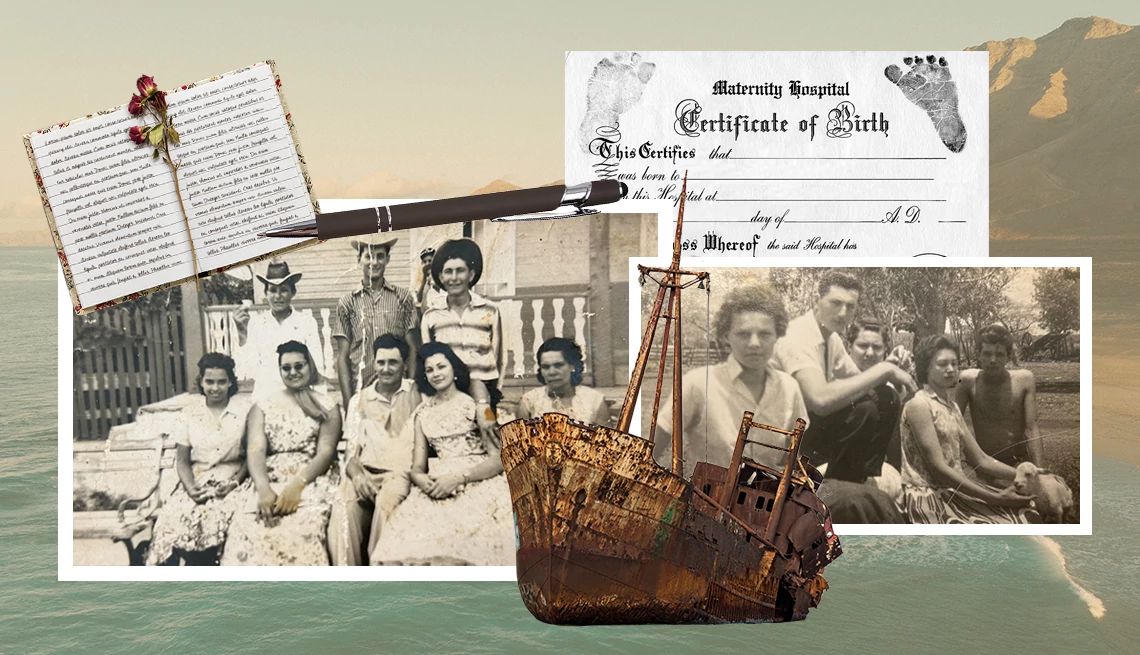

Recurring dreams of searching for a daughter she never had. A lifelong fear of the ocean. The startling discovery that her mother’s beloved grandmother is listed among the dead of a long-lost shipwreck. In Deeper Than the Ocean, writer Mirta Ojito’s first foray into fiction, one woman’s search for answers sets her on a journey of self-discovery and unexpected revelations that hook the reader from the first page to the last.

It’s a saga told in a dual narrative that spans more than a century, three continents and five generations of one family. Using alternating chapters that trace the stories of the two principal heroines — Catalina Quintana, born in the Canary Islands at the turn of the 20th century, and her great-granddaughter Mara Denis, a modern-day journalist working and living in New York and Spain — the book delivers all that historical fiction fans could want: There’s passion. Love. Loss. The Old World, the New World. The real shipwreck of the Valbanera, a Spanish steamer headed for Havana whose 488 passengers and crewmen perished in 1919 off the coast of Key West. And a modern quest for identity and home that uncovers long-guarded family secrets.

For Ojito, 61, a Pulitzer Prize- and Emmy Award-winning journalist with two nonfiction books to her name, the switch to fiction writing was unexpectedly cathartic.

“I discovered that when you’re in the creative process, which is a wonderful, amazing headspace that I did not feel during my nonfiction books, this was something different and magical and absolutely glorious,” Ojito says. “I cannot wait to go back to it.”

It is, Ojito says, the book she owed her late mother and thinks of it as her mother’s last gift to her.

Although she had initially set out to write about the Valbanera, Ojito, who arrived in the United States during the five months of mass migration from Cuba known as the Mariel boatlift in 1980 — a moment in history documented in her first book, Finding Mañana: A Memoir of a Cuban Exodus — soon found herself weaving in many of the stories her mother told her about her own ancestors.

The result is a seductive narrative that explores love, marriage, family and, above all, the relationship between mothers and daughters. It takes an unflinching yet compassionate look at lives caught in the inexorable forces of historical events, traditions, customs and expectations. At times, Deeper Than the Ocean is reminiscent of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate or María Dueñas’ The Vineyard. AARP interviewed Ojito at her home in Coral Gables, Florida, ahead of the book’s Nov. 4 release.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You have made a career as a journalist and an editor and authored two nonfiction books, Finding Mañana and Hunting Season: Immigration and Murder in an All-American Town. Now, at 61, you surprise us with your debut novel. Is this a book you always thought you would write, or did it surprise you as well?

To me, the big surprise is that I write books at all. I always thought of myself as a journalist and only as a journalist. But then the first book happened, Finding Mañana, and it was a big success on many levels. And then the second book happened. So I’m on this path now: I’m going to write books. But I have a very demanding full-time job. The idea of dedicating the amount of time that I do to report a nonfiction book was just daunting. So I thought, OK, I’m just going to have to write a novel. That was in 2014.

So it’s been percolating for the past 10 years?

For a lot longer. In 2006, I found this book El misterio del Valbanera in a shop in Key West. It was like $10 and about a shipwreck off the coast of Key West in 1919, and I thought, How come I didn’t know about this? The more I looked into it, the more an idea began forming in my head: I have to write about this. But I couldn’t dedicate the time to write a proper nonfiction book, and then I thought, Well, I’ll turn it into a novel. I began writing it little by little, and it’s been almost 20 years, believe it or not.

How different was the process of writing fiction versus nonfiction?

Well, I can tell you that in nonfiction, I never would have dared to write about a place where I had never been, and I had never been to the Canary Islands until January this year. When you write fiction, there’s so much freedom. It’s just me and my laptop. My sense of responsibility is only to writing a good story. While with nonfiction, you have the responsibility of writing a good story that’s also true.

But you’re no stranger to Spain.

When I was teaching, I used to spend my summers there. But always in the north, which is why I place Mara in Santander. That’s my home away from home.

In a way, I was also inspired by the fact that Spain has opened its doors to the children and grandchildren of Spanish citizens all over the Americas. I know so many people who are applying for [Spanish] citizenship and who are looking for their papers.

More From AARP

10 Classic Novels to Add to Your Reading List

Check out our list of iconic books from Austen, Woolf, Orwell and more

39 Words Added to English Dictionaries

Learn the meanings of ‘delulu,’ ‘touch grass’ and ‘broligarchy’

The 75 Essential Books for Gen Xers

Remembering the reads that entertained us, taught us and shaped us into who we’ve become