AARP Hearing Center

Jann Wenner’s new memoir Like a Rolling Stone (Sept. 13) takes readers through his heady years as editor and publisher of Rolling Stone, the most influential music and pop culture publication of its era. He describes its founding in 1967, hiring the then-unknown photographer Annie Leibovitz, and his friendships (and, often, wild partying) with many of the legendary figures featured in the magazine — John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Mick Jagger, Bono and more.

Enjoy some highlights, excerpted from Like a Rolling Stone, below.

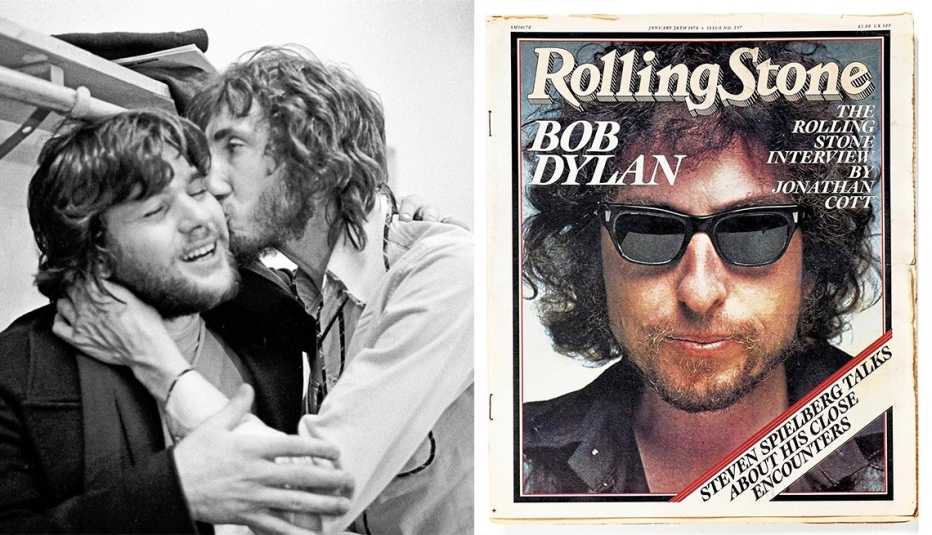

Pete Townshend

The Who were headlining for the hippies at the Fillmore and Pete suggested we meet at my house, after his last show. He arrived at 2 a.m., not ready to wind down. Pete loves to talk, he loves to think, and he loves to ramble about his many strong opinions, which often contradict one another. We talked about his guitar smashing: when he started it and why, how he felt while doing it and after it was over. We mostly talked about the history of the Who and their future. Pete said: “We have been talking about doing an opera called Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Boy, and the hero is played by the Who. We want to create the feeling that when you listen to the music you can actually become aware of the boy. He sees things as vibrations, which we translate as music. The boy elevates and finds something incredible.”

Pete told me later that this was the first time he had articulated the concept for Tommy. I took him to the airport the next day. He asked if I had spiked his orange juice with acid the night before. I hadn’t. It was pure Pete.

He became a pen pal. “The big drag about The Who is that they always lean so heavily on their history,” he wrote. “Anything slightly daring throws everyone into panics. I feel I can put a time limit on how much longer we’ll be together. I give it 18 months.”

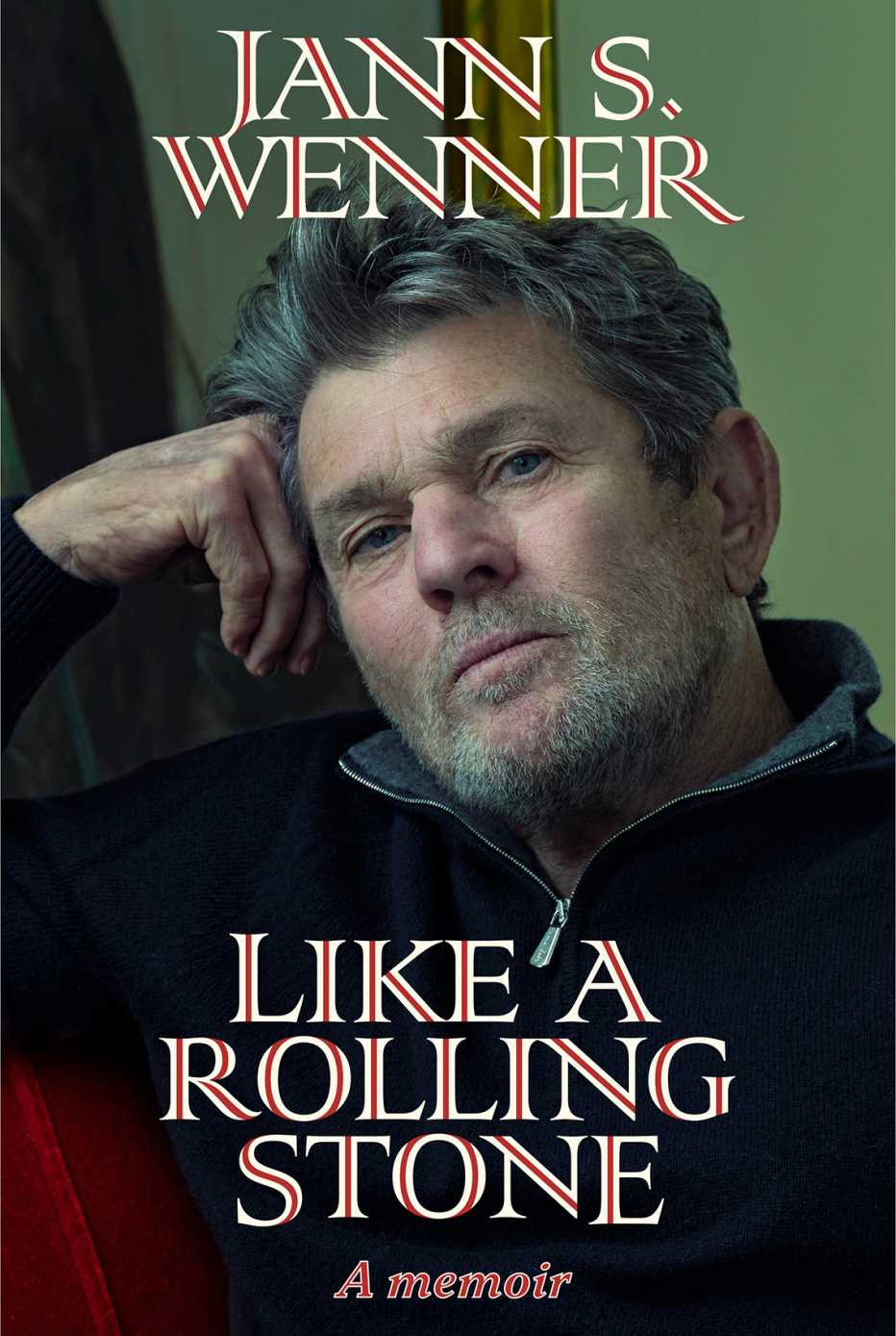

Bob Dylan

I met with Bob at the Stanhope Hotel on East 81st Street and Fifth Avenue. He was clean-cut, neatly dressed and carried a book bag. He came alone; this was in those less fraught early days without PR people. His answers were simple and direct. If Bob didn’t want to answer, he wasn’t evasive, but he would just stay silent until I felt completely awkward and moved on.

“Well, Jann,” he said. “I’ll tell ya, I was on the road for almost five years. It wore me down. I was on drugs, a lot of things. A lot of things just to keep going. And I don’t want to live that way anymore. I’m just waiting for a better time.”

“Do you think you’ve played any role in the change of popular music in the last four years?”

“I hope not.”

“Well, a lot of people say you have.”

“Well, you know, I’m not one to argue. I don’t want to make anyone worry about it, but boy, if I could ease someone’s mind, I’d be the first one to do it. I want to lighten every load. Straighten out every burden. I don’t want anybody to be hung up … especially over me or anything I do.”

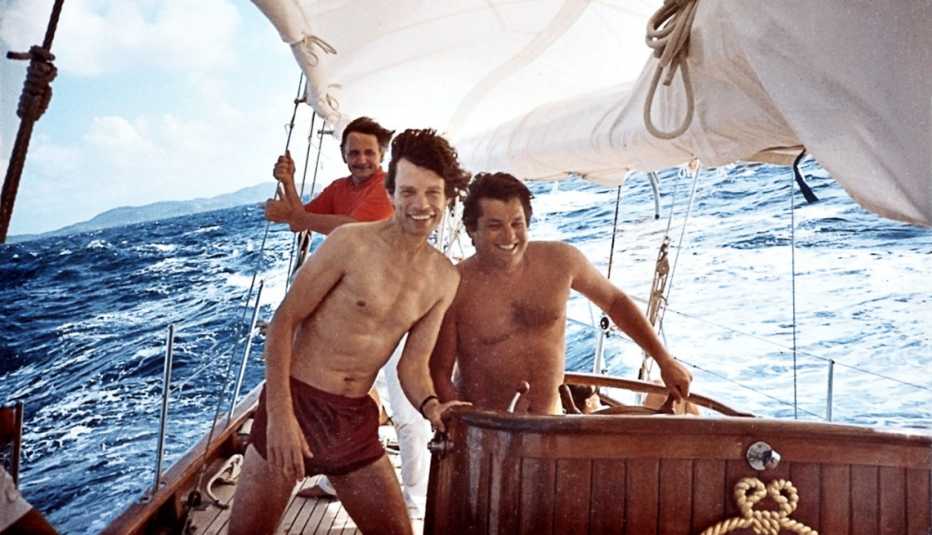

Mick Jagger

I first met Mick Jagger when I was 22 and he was 25. It was in July 1968. Jane and I were on our honeymoon, poolside with the Steve Miller Band, at a hotel in Hollywood. Mick was in town remixing Beggars Banquet with Glyn Johns, who was also producing Steve’s record. Mick had a soft handshake and a soft voice; he was wearing a dress shirt with pressed trousers, definitely not a rock star outfit. But a rock star he surely was. He made me feel comfortable right away.

I sat at the mixing board between Glyn and Mick, and suddenly out of this supersonic sound system came “Street Fighting Man.” They played it again and again as they mixed it, stunning on first listen, absolutely incredible as the song became more familiar. They also worked on “No Expectations.” Then Mick stopped the mixing and told me he had finished one more, and would I like to hear it? It was “Sympathy for the Devil.” The final take had been done the day after Bobby Kennedy had been gunned down, and Mick added the lines, “I shouted out, ‘Who killed the Kennedys?’ After all, it was you and me.”

Mick took me in his red Cadillac convertible to the house he had rented in Beverly Hills, where he had the test pressing of a new record to play for me that had knocked him out. It was the first time I heard Music From Big Pink (the debut album by the Band). We spent a long time talking about music and so many other things. It was a great start to a friendship.

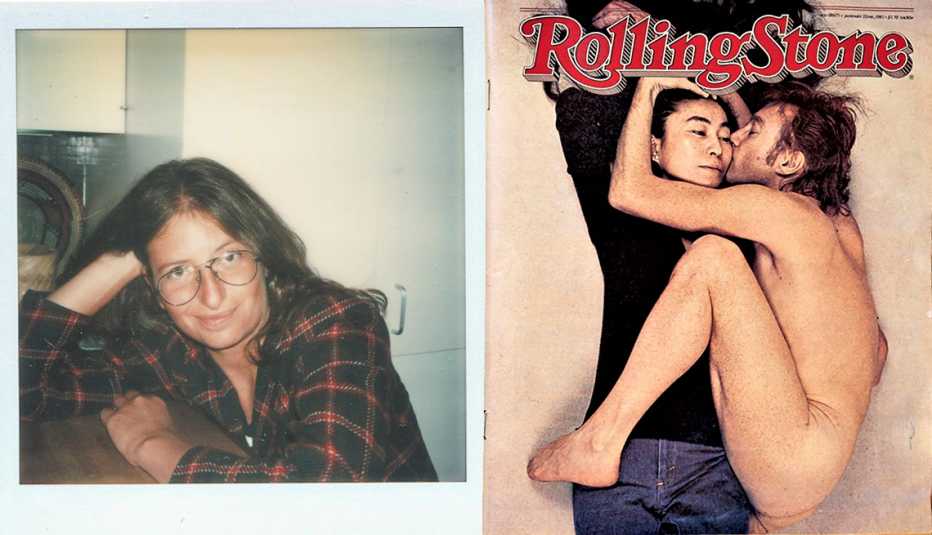

Annie Leibovitz

Annie Leibovitz would barrel into the office, 6 feet tall, wild hair, still in her early 20s, with the energy and enthusiasm to do anything we asked. She had been a painting major and bought her first camera two years earlier. A military brat, she was the third of six children, her father a career Air Force officer, her mom a dance instructor. No one could have imagined the light within.

Her first cover shoot, in 1970, was Grace Slick. The inside portrait of Grace and Paul Kantner in bed, playing with their new baby, China, foreshadowed Annie’s trademark reportorial style: finding a casual, personal moment that had the power of unexpected intimacy. Another thing Annie brought us was the emergence of a feminine energy and point of view in what was an all-male shop.