Staying Fit

Mirta Ojito, AARP

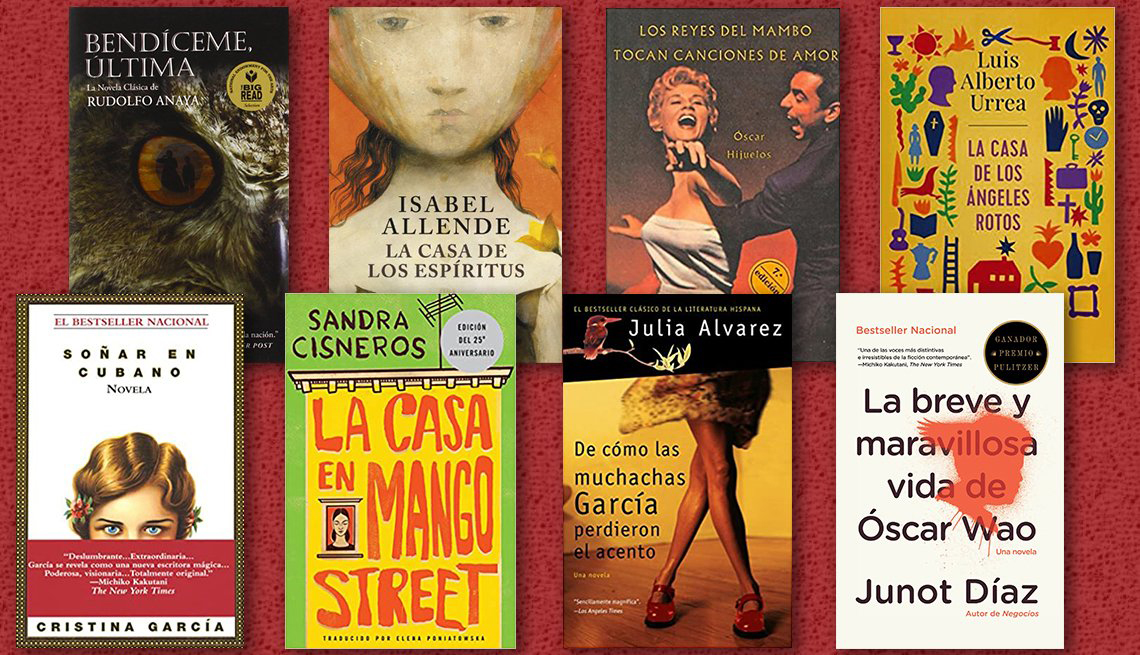

Books written by Latino authors in the United States offer us a wide range of voices, themes, and styles — from magical realism to the starkest urban reality. With varying degrees of familiarity in both languages, these writers no longer hide their bilingualism, blending Spanish and English seamlessly, shamelessly and often without quotation marks. And their talents have been amply recognized — Pulitzer Prizes, MacArthur fellowships, Guggenheim fellowships and presidential medals.

Among so much talent, we have focused on 12 writers who have broken barriers, opened doors, raised bars or continue to explore the vexing issues that Latinos face in the 21st century. This list serves as a starting point for the uninitiated, and as a reminder for those who have already lost themselves in the magical worlds these authors have created over the years. Writers are listed in chronological order according to birthdate.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

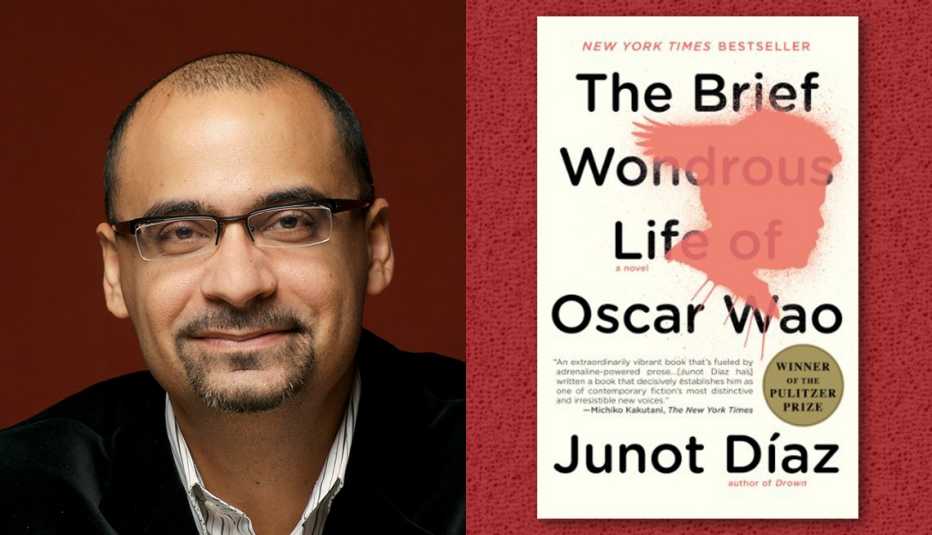

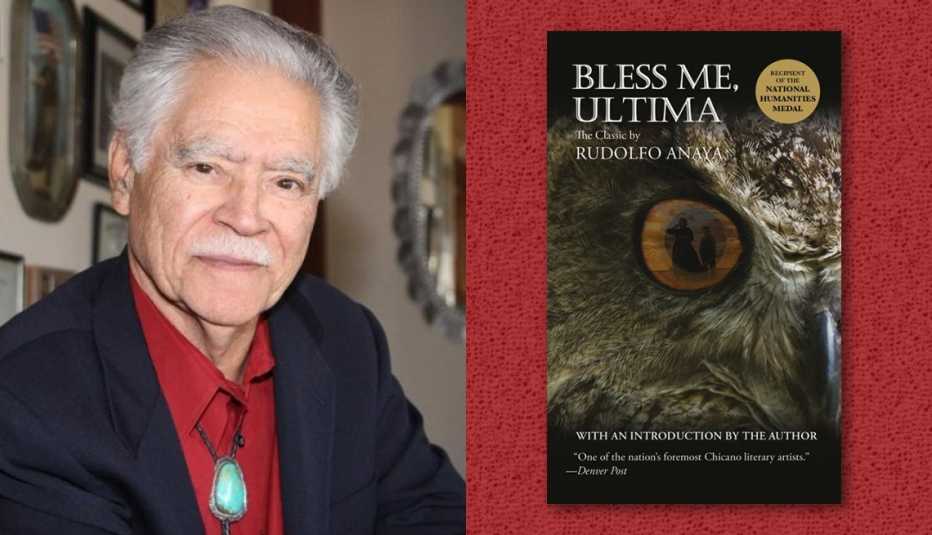

Rudolfo Anaya (1937-2020)

Long considered the father of Chicano literature in English, Anaya wrote novels, children’s books — such as La Llorona: The Crying Woman and The Farolitos of Christmas — and even plays, but he is most well-known for Bless Me, Ultima. When that novel was published, in 1972, it was lauded by critics as “avant-garde” and “extraordinary” for the way it dealt with issues of identity and Chicano culture; until then, these had not been part of the U.S. literary canon. Anaya, who was born in New Mexico in 1937 and died just last year, did not have a formal education in creative writing. That is why — as he recounts in the introduction of his first book — it took him seven drafts and late-night pounding on an old Smith Corona typewriter to get it published. The novel is about the impact the healer Ultima had on a man's life and how she helped him to discover himself and the secrets buried in his Latin soul.

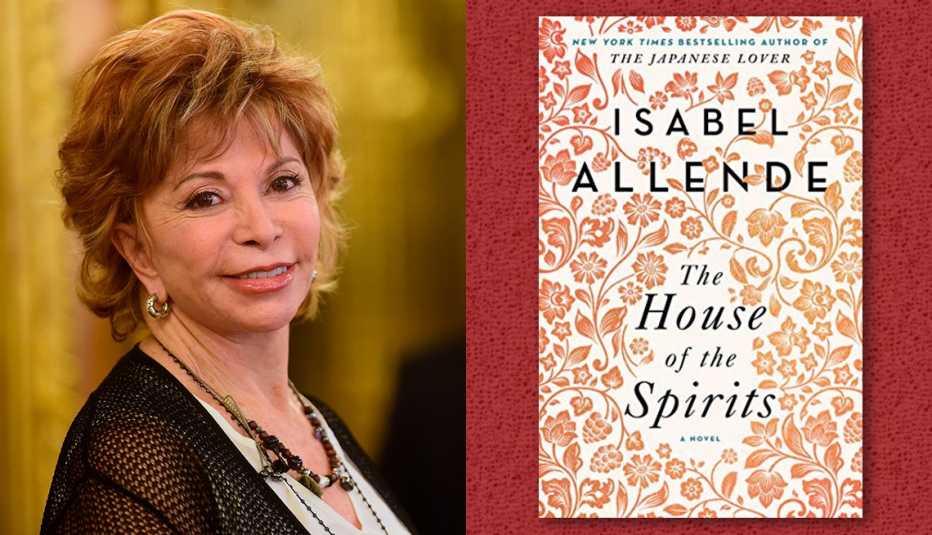

Isabel Allende (born 1942)

Allende was already a famous Chilean author before transforming into a U.S. Latina writer upon moving to California more than 30 years ago. Without losing an ounce of the magic that had long characterized her work, Allende was able to understand the complexities of latinidad and incorporate into her novels elements of the harsh reality many Latinos face in the United States. Having written classics like The House of the Spirits, Paula, and Inés of My Soul, Allende began to write about the lives of undocumented immigrants, the drug epidemic plaguing the youth and intergenerational conflicts. Her most recent book, The Soul of a Woman, is a compelling memoir of her life as a lifelong feminist. In A Long Petal of the Sea, published right before the pandemic, Allende explores familiar themes from past works: immigration, love and war. Perhaps Allende's most important legacy has been to demonstrate that, even living in the United States, she can sell novels written in Spanish all over the world, translated into many different languages, including English.

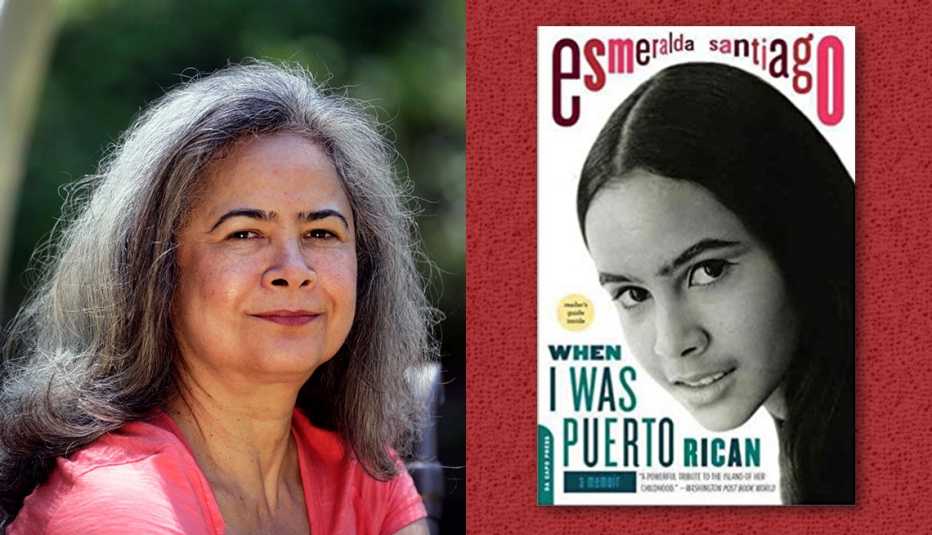

Esmeralda Santiago (born 1948)

With her first memoir, When I Was Puerto Rican, Santiago introduced the Puerto Rican countryside into the collective imagination of Hispanic literature. She tells the story of her life with such specificity that it achieved universality. But she did not stop there. Santiago's readers watched her grow — as a woman and as an author — in her next two memoirs: Almost a Woman, in which she explores the trauma of immigration, and The Turkish Lover, in which she narrates the confusion and heartbreak of young love. Although Santiago has written other books, notably Conquistadora, it was her trilogy of memoirs that ensured her a place among must-read Latino authors, for giving Puerto Rico and its people the place they deserve in Hispanic literature.

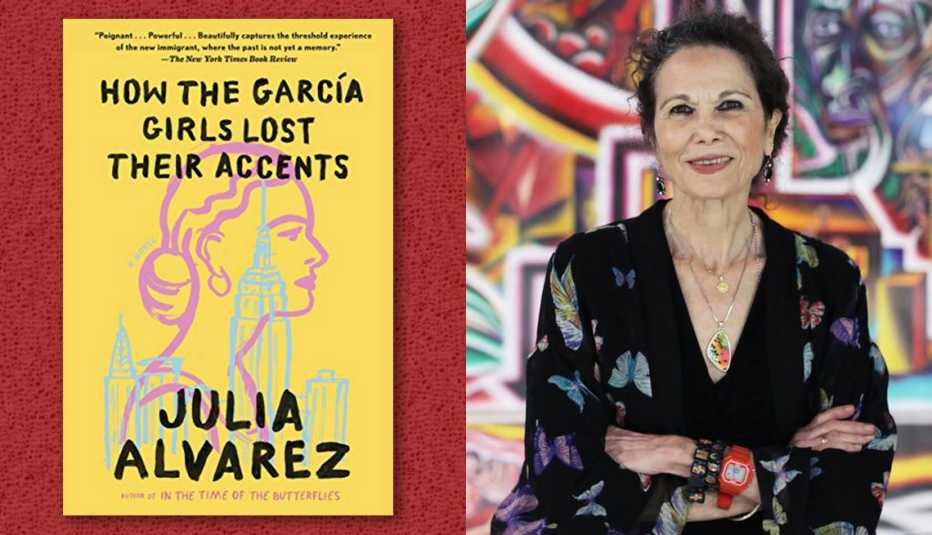

Julia Alvarez (born 1950)

With her first book of interconnected stories, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, this Dominican author dove headfirst into the most complex and riveting problem those who have crossed the border face daily: How do we become part of the U.S. without losing our identities? How do we lose our accents without losing everything else? The book, published in 1991, became a point of reference among Latinos, inspiring a new generation to write about assimilation. Alvarez, who celebrated her 71st birthday in March, published a novel in 2020, Afterlife, in which she deals with the transition toward retirement and widowhood in the current political climate, addressing the fear of undocumented immigrants and the difficulties they encounter when working and living in the United States. Through her latest work, Alvarez remains current, taking notes on her own life and — with a critical eye — paying attention to the vicissitudes of U.S. society.

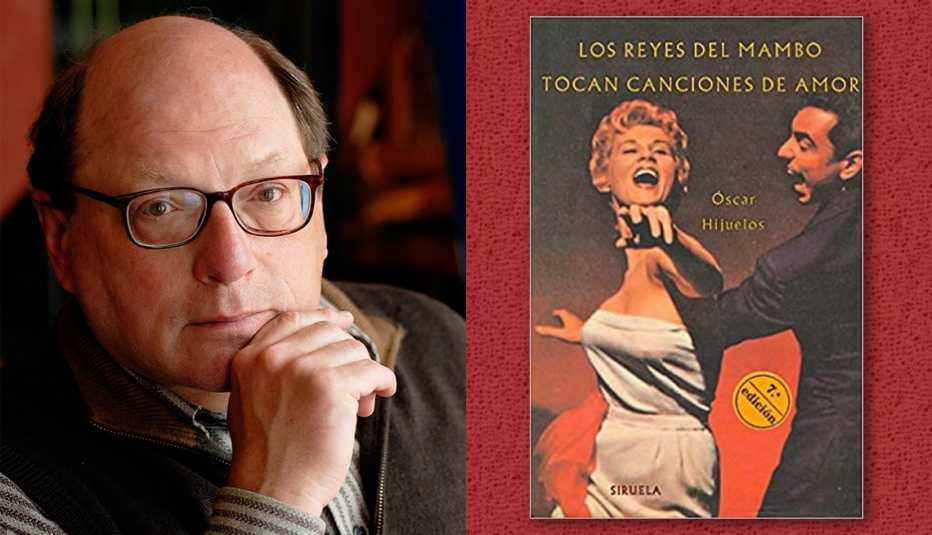

Oscar Hijuelos (1951-2013)

In 1990, Hijuelos became the first Hispanic writer to win the Pulitzer Prize for his second novel, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love. The prestigious award paved the road not only for him but also for other Latino authors, who until then had been mostly ignored by reviewers and publishers. Hijuelos, the son of Cuban immigrants who came to New York in the 1940s, depicts in his novels the rich world of immigrants and their struggles, a topic that resonates and holds true to this day. His protagonists are dishwashers, cooks, maids and musicians — all united by an impossible dream: to redeem themselves of the decision to leave behind their countries and the ones they love in search of a better life. His first published work, Our House in the Last World, is a meditation on the insurmountable trauma of immigration and the open wound that remains in some families because of it. Hijuelos died in 2013; contrary to many of the characters in his novels, he died in the place where he was born, the city that cradled and defined his work—New York.

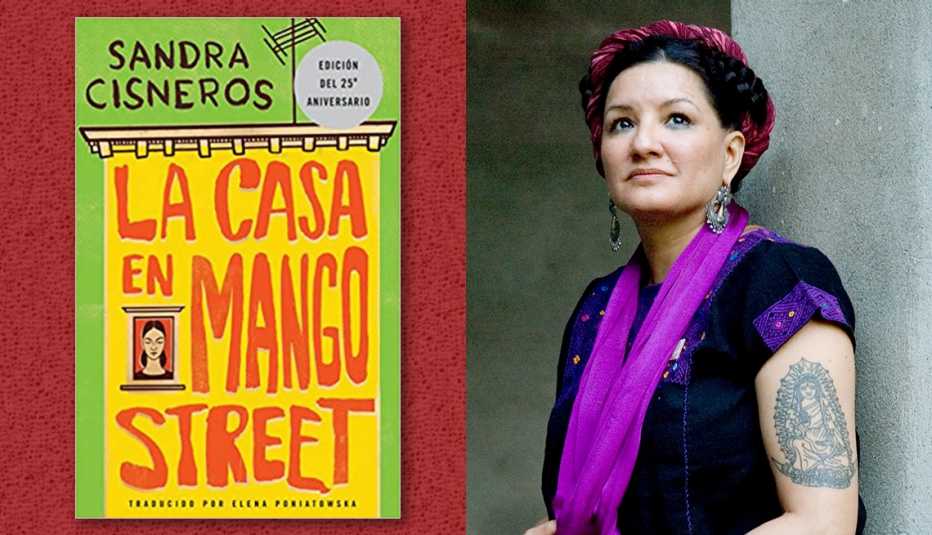

Sandra Cisneros (born 1954)

This Chicago-born Chicana writer has done it all: collections of poetry, essays, short stories, novels and children’s books. But anyone new to Cisneros should consider starting at the very beginning with her seminal first novel, The House on Mango Street. Published in 1984 — and based on the difficult working-class Latino lives Cisneros witnessed as a high school counselor — this novel is told in a series of lyrical vignettes from the point of view of Esperanza Cordero, a young Latina girl coming of age in Chicago. Since its publication, The House on Mango Street has sold over 6 million copies, been translated into more than 20 languages and become a staple in school curriculums across the country. Those wanting to get to know the author further can delve into Vintage Cisneros, a skillfully edited volume that contains excerpts from Woman Hollering Creek, Caramelo, and other notable works by the MacArthur fellow winner. Cisneros’ most recent work is Martita, I Remember You, published this year, a bilingual novella that features the signature blend of lyricism and realism that has come to define Cisneros' career.