AARP Hearing Center

Chapter 3

1993

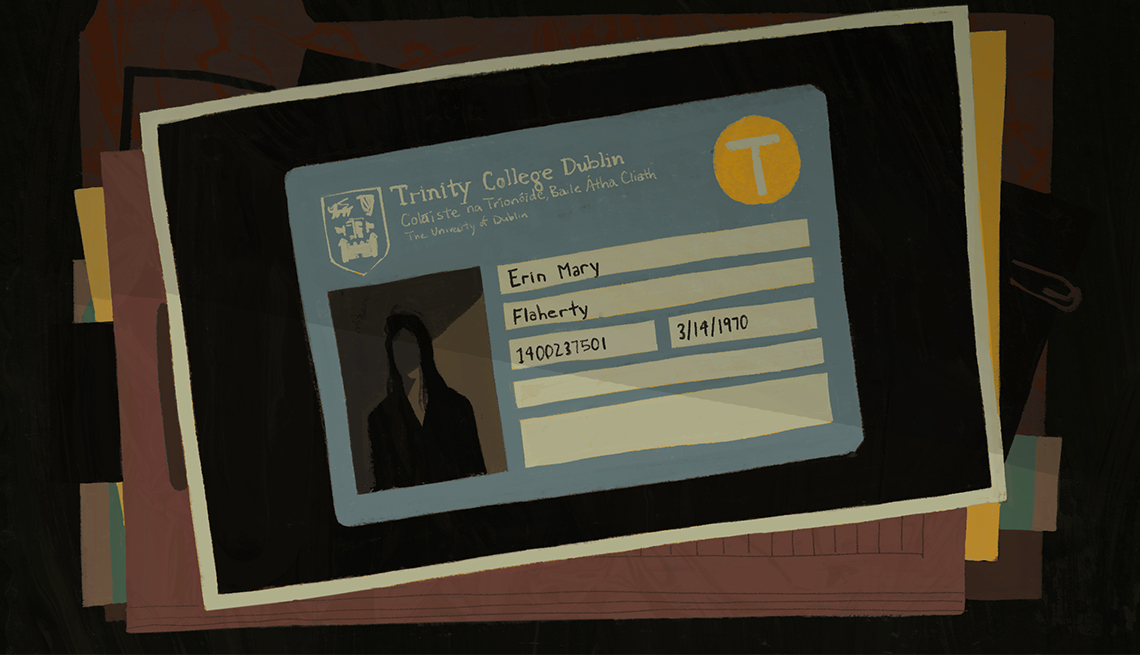

I WAS TWENTY-TWO THAT FALL, a too-thin girl with shoulder-length brown hair that I always wore scraped back in a ponytail, working at the bar to help out Uncle Danny, training for a marathon, and trying to stop my dad from drinking too much. I’d graduated from Notre Dame the spring before, after taking a semester off as my mom was dying and then finishing up the last of my coursework at the bar when things were quiet. I think I can say with complete honesty that I had no inkling, at that point, of my future career path, but I was curious about people and I knew, from bartending and from studying literature for four years, that people lie all the time, and that the interesting thing is not that they lie, but why they do. Now I know that this is a lot of it, of being a detective, and that perhaps I was setting off on some inevitable path that night we got the call from Dublin.

I was working a long shift with Uncle Danny, serving beers and vodka and rum and Cokes to the cops and the plumbers and the bankers off the train, when the phone rang at the bar.

“Is Mr. Flaherty there?” I recognized the accent as Irish, real Irish, and for just a moment I thought it was Erin, that somehow she’d picked up an accent since moving to Dublin almost a year before. I handed it to Uncle Danny and listened as he said, “Oh, no, I haven’t heard from her. She didn’t leave a note? No. Okay. Thanks. We’ll ... yes, we’ll get back to ya.”

“That was Erin’s roommates over there in Dublin,” he said, hesitating for a moment and then starting to wipe the bar down. “Eeemur or somesuch, one of those real Irishy names. She hasn’t been back to her place for a while. They got worried and thought they oughta call. Whaddya think, Mags? Ya think she’s okay?” His voice caught and I rubbed little circles on his shoulder. I could already feel the anger rising through my throat.

Do you know how worried Uncle Danny is about you?

Why do you always do this, Erin?

“I’m sure she’s fine,” I told him. “I bet she’ll be back.” But Erin wasn’t back the next day.

My dad came by the bar after work to talk about what to do.

Two old men. That’s what I thought when I came up from the basement and saw them. Uncle Danny was wearing one of his shiny golf shirts and the fabric was lighter where it stretched over his belly. My dad was just off the train from the city, still in a gray suit that had gotten too big for him, his blue eyes the only alive thing in his face. My mom had been gone for a year and a bit and he wasn’t over it. He was pale, shaky. He didn’t sleep much. I watched him stir the gin in front of him on the bar.

They tossed it around for a bit, Uncle Danny going over, maybe my dad.

“I wish Father Anthony was here,” Danny said. “He’d know what to do. God rest him. I guess I’d better go over.”

I stepped in after Uncle Danny started coughing and couldn’t stop.

“I’ll go,” I told them. “I can go look into it. Uncle Danny, your heart.”

They barely tried to stop me. Two old men. I felt guilty for thinking it, but it was true. Uncle Danny. I kept finding cigarettes hidden in his desk in the office at the bar. He reeked of them. His doctor said he was a heart attack waiting to happen if he didn’t cut out the smokes and lose some weight.

“I’ll go,” I told them again. “And then once I figure out what’s going on, you can come over. Hopefully she’s just ...” We let it sit there, all the possibilities contained in that hopefully.

“Okay, baby. Thanks. That’s a good idea. I can come when you figure out what’s going on.”

***

I arrived in Dublin on a wet, gray morning, the first of October. The airport was a ’70s movie, psychedelic carpet, cigarette smoke thick in the arrivals hall. Ireland. Cold wet air swept through me when I walked outside to find a cab. The accents were familiar from the bar, where we always had a guy or two just off the plane, but they took on a different quality when they filled all the spaces around me, looser, more confident. Changing money, I was conscious of my own accent, the nasal of it, the loud upward pitch of my words. The cabdriver was a skinny, leggy old man who said, “God bless you now, love. Take care o’ yourself,” when I got out at Erin’s house.

Gordon Street was a little side street near a canal, a twisting narrow lane of squat little stucco one- and two-story houses, almost in miniature, with brick or red-painted facades and a few doors painted bright blue, a few shabbier ones painted black or dull red. Looming over the rooftops was a huge round structure shaped like a crown, and there was a Virgin Mary statue tucked into an alcove on the sidewalk. Children played and shouted in the street, their cheeks pink from the cold. With a little thrill of recognition, I thought, The cold air stung us and we played till our bodies glowed.

Ireland. It wasn’t the way I thought I’d get here. I’d been about to spend my junior year studying at Trinity when my mom got sick. Lately I’d been thinking about graduate school. The brochures from Trinity and UCD were still in the top drawer of my desk.

Ireland. I could smell the ocean and something like woodsmoke and I inhaled deeply, clearing the stale odor of the cab from my nose. As I stood there, the sun broke through the clouds for a moment and illuminated the wet sidewalks, throwing the little row houses and brightly painted doors into impossibly beautiful color. It stopped me for a minute, the sheer magic gorgeousness of it, all the saturated reds and browns and blues, the light, the proportions of the houses, the shine of a silver car parked against the curb.

Erin’s roommates were named Emer Nolan and Daisy Nugent. Emer, blond, round-faced, cheerful, was the one who had called the bar, and she took the lead once they let me in, showing me Erin’s tiny room, barely a closet, with a small twin bed and a folding table set up as a desk.

They showed me the work schedule pinned on the wall over the desk and wrote down the address of the café where Erin worked.

I got out my agenda book and had them show me the day she left. September 16. I circled it in green pen. “She didn’t tell you that she was going on a trip or anything, did she?” They shook their heads.

“We got home from class and she’d gone already. Her rucksack wasn’t in the press, so we thought she’d just gone traveling. She’d done it before.”

“Did she ever talk about friends from work?” I asked them.

They glanced at each other. “There were some girls she went out dancing with a few times, and your man came by to see if she was sick when she missed work. But other than that, I don’t think so.”

“My who?” I was tired, jet-lagged from the red eye, off center in this unfamiliar place, their accents taking all my concentration.

“Sorry, the fella at her job. Conor. He came by Monday and we said we hadn’t seen her. That’s when we thought we should ring up your uncle.”

It didn’t take long to check her room. I didn’t know what she’d brought with her to Ireland when she’d moved over in January but there weren’t a lot of clothes in the closet: a couple of short black dresses that I knew she wore to go out, two floral blouses, a couple of pairs of faded Levi’s. There was a heavy Aran sweater folded on the shelf over the hanging clothes, and a couple of cotton sweaters. Wherever she was, she must be wearing her brown leather jacket. She got it for herself for her birthday the year after she graduated from high school, and when you hugged her, the jacket smelled of new leather, cigarette smoke, and faintly of her perfume; the leather always felt cold to the touch. The velvet scarf I gave her for Christmas, green and blue, with thicker velvet butterflies gathering at one corner, wasn’t in the room, either, so she must be wearing that. Her claddagh necklace, a high school graduation present from Father Anthony, wasn’t in the little white box printed with a claddagh on the front that I found tucked into her underwear drawer. I could close my eyes and picture her wearing it, the delicate silver chain, the silver hands and purple amethyst heart in the center. I hadn’t seen her without the necklace in five years. She must be wearing it too. Wherever she was.

A blue paper packet of photographs sat on top of a stack of bank statements and papers on the makeshift desk. They’d been printed at a photo shop in Dublin, and when I took them out and leafed through them, I found a few of what I thought were Dublin landmarks—I recognized Trinity College—and the rest seemed to have been taken in the country, trees and mountains and what looked like an abandoned school: gray buildings, empty windows, grass growing up around the foundation.

I sat on Erin’s bed for a moment, then brushed my teeth and washed my face in the tiny bathroom at the end of the hall. I told Emer and Daisy that I was going to the café and didn’t know when I’d be back. “Conor, right? That’s the guy she worked with?”

“Yeah,” Emer said. They were staring at me, their faces in shadow in the dark little hallway.

“What?” I asked.

“It’s, it’s only,” Daisy stammered, “you have the look of her. It’s a bit weird.”

I pushed down a flash of annoyance. “I know. Everyone says that. What are these pictures of?” I held out the stack and Daisy took it from me, looking through them slowly.

“Four Courts, Grafton Street, Trinity. Here in Dublin,” she said. “The others I don’t know about. Wicklow maybe. She has a little camera.” I tucked the packet of prints into my backpack.

Outside, the clouds were racing across the sky, a time-lapse movie. When they made space for the sun, the slightly shabby street was saturated with color and life again, the white lace curtains in the windows pristine before the clouds covered the sun and they went back to a dingy gray.

***

It took me twenty minutes to walk to Trinity College and the center of the city. I walked into a stiff wind the whole way, past a square of sober gray houses and a small park, and men in overcoats walking fast, their heads down, and old ladies in rain bonnets pushing shopping trolleys. I breathed the sour smell of beer pouring out of empty pubs and the steam rising from the backs of buildings. It was late morning now, but I had the sense of a city waking, a few students returning from nights out, long coats clutched around them. I didn’t linger outside the gray walls of the college or wander the lanes around Grafton Street, brimming with bookshops and little businesses behind glass windows.

The café—“The Garden of Eating,” Emer had told me, rolling her eyes—was in a section of the city labeled “Temple Bar” on my map, a close little collection of narrow streets between a broad avenue called Dame Street and the river Liffey. It was grittier and more bohemian than the streets around the college; the colorful shopfronts and tiny lanes made it seem like a separate section of the city. Wild drumming came from a second-story window; a band practiced behind half-open garage doors. Workmen sat on buckets and smoked in front of a construction site.

A bit of graffiti on one wall read, “Long Live U2!” Someone else had written, “Wankers!”

At eleven a.m., the pubs lining the little streets were mostly quiet. The Garden of Eating, down a narrow, cobblestoned street called Essex Street, was open, though, and a guy behind the counter was dumping coleslaw and bean salads from huge aluminum mixing bowls into rectangular containers. The place felt more like a cafeteria than a café. There was a hammer and sickle painted on one wall and a sign over the counter that read, “No Man (Or Woman) Shall Go Hungry! Ask And Ye Shall Eat!” A tattered poster of a neon-haired troll with the word Norge was thumbtacked on one wall.

“Can I ...?” the guy started, but as soon as he saw me, he stopped and stared openly at my face. He looked confused, terrified, happy—all of those things in one moment and it made me pay attention immediately. It felt like a jolt of caffeine, sharpening all my perceptions, speeding my heart. He thought I was Erin, and he was happy to see her and somewhat surprised. Remember that, I told myself.

He was tall, dark-haired, and dark-eyed, a face full of interesting angles and dimples, Irish-looking in a way I’d never be able to put into words. He was wearing an apron and black jeans and a wool sweater in heathery shades of blue and brown.

“I know what you’re thinking,” I said quickly. “I’m Erin Flaherty’s cousin. I know I look like her.”

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members