Staying Fit

Driving up Interstate 95, my eyes dart about in a triangle — out the windshield, to the navigation system and to an electronic display counting down toward trouble. As the miles tick away, closing in on the point at which this orange hatchback will conk out, I feel escalating anxiety: Will I get where I’m going? For me, unlike for the thousands of fellow drivers barreling along this congested stretch of Virginia highway, those “Gas — Next Exit” signs provide no comfort. No one sells electricity by the gallon.

It’s been 35 years since I earned my license in Mom’s AMC Hornet, but this is a first. I’d road tested a varied fleet — the ridiculous roadster of my 20s, the sensible sedan of post-marriage, the hulking minivan once the kids came on board, plus who knows how many vacation rentals, from subcompacts to SUVs. But each had this constant under the hood: an internal combustion engine burning gasoline.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Take the AARP Smart Driver course online or find a course near you

Manufacturers have teased us with electric vehicles (or EVs) before. Their history dates back more than 100 years. But emissions-free cars that quietly whoosh along our streets? That was the stuff of some fantastic future, not a practical present. Well, the future has arrived. And I am driving straight into it.

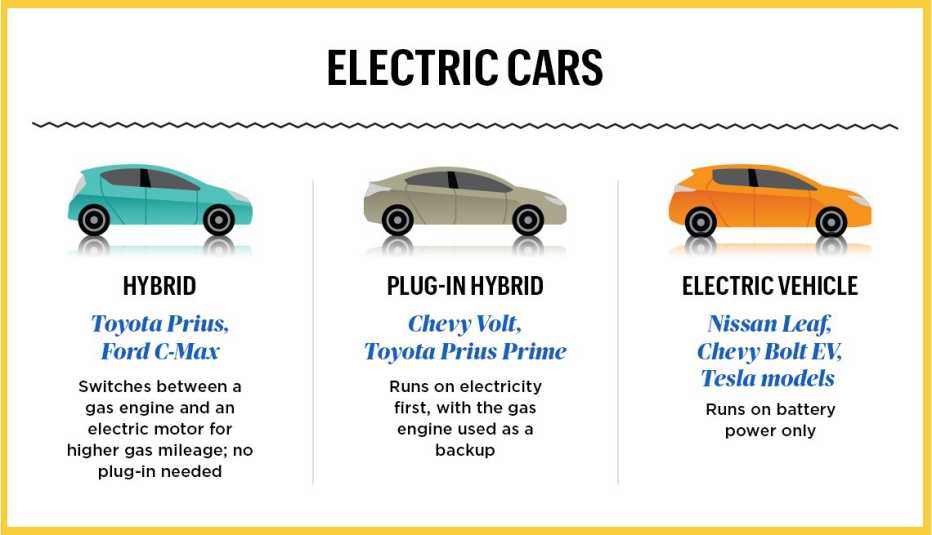

I tried out two electric cars over the course of a week. Both were full-on battery powered, unlike a Toyota Prius or other hybrids, which use electric motors to supplement a gas engine. These electric cars plug in for power and are propelled by the same kind of lithium-ion batteries that run our cellphones and laptops. First up was a sporty red Tesla Model 3 (the current base price is $46,000, although the company promises that a $35,000 version is to come). Tesla, the famous start-up that exclusively makes electric cars, has been the lead driver in the gasless movement over the past decade, making souped-up products that appeal to American car culture as much as to the eco-crowd.

“You can’t start by mass-manufacturing a car when there’s no demand for it. You have to develop the interest,” says Chris Paine, director of the popular documentaries Who Killed the Electric Car? and Revenge of the Electric Car. “Make it the object of desire. Make it as cool and amazing as the highest-end car.”

The strategy is working. Tesla recently surpassed both Mercedes-Benz and BMW in U.S. sales. As Tesla has grown, the big automakers have taken note. Nissan, Volkswagen and Hyundai are just a few of the companies now producing electric cars. A study by Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that electric cars will make up 55 percent of global new-car sales by 2040, as technology improves and prices decrease. Even General Motors, which infamously launched and then discontinued an EV in the 1990s (the subject of Paine’s first film), has gotten in on the trend — with the Chevrolet Bolt EV, a small plug-in family vehicle that sells for $37,500 and up. This is the second car I get to whirl around in.

The first thing that amazes me — and the passengers on my joyrides — is this: Electric cars haul you-know-what. The internal combustion engine is a complex machine, with little explosions and bobbing pistons and grinding gears. EVs are much simpler, mechanically. Their energy is stored rather than generated. So when I step on the accelerator: boom, instant power. It just goes. Fast. Ever ride one of those roller coasters with no first hill, the kind that just shoots you out of the station using some kind of magnetic propulsion? That’s what the sleek Tesla feels like. The Chevy Bolt EV, a small crossover vehicle that sits up higher, also has surprising zip.

Slowing down is also dramatically different. Instead of brake pads rubbing against wheels, a giant friction fight against momentum, an EV also uses its electric motor for more stable deceleration. As I take my foot off the pedal, the car does not coast but starts to slow — off-putting at first, after three-plus decades of driving cars a certain way. But I quickly get used to it, and in a short time my right foot and the accelerator become extensions of each other. I barely need to use the brake at all.

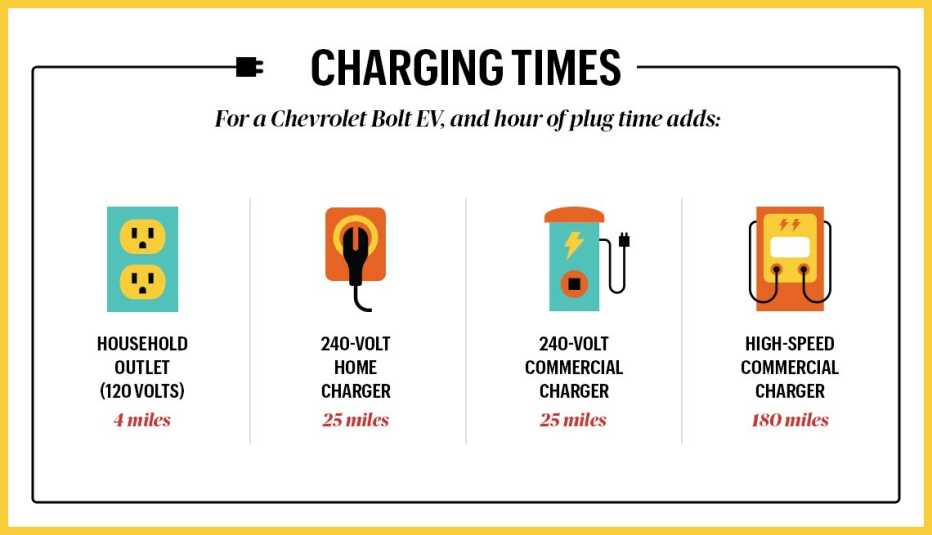

While both cars are fun to drive, having to constantly worry about range, charging and time is a major drawback. “Where will I charge it?” (I’ll do this at home overnight, but as it turns out, the parking garage by my office also has a charger I can use for free.) “How long does it take to charge?” (This depends on the type of charger, but the key is to change your attitude about “refueling,” from active — pull into a station when you need it — to passive: Fuel as much as possible whenever it’s parked.) “Doesn’t it run up your electric bill?” (It’s still cheaper than gas; the cars rate at more than 100 miles per gallon in equivalent energy used.) And the big question: “How far will it go?” (The Chevy or the Tesla may last over 240 miles on a charge.) Turns out the largest barrier to consumer acceptance of EVs is what I experienced: “range anxiety.”