AARP Hearing Center

When Phyllis Bermudez goes grocery shopping, she puts a few of the pricier items, like eggs and bacon, at the back of her cart. Then she waits for the cashier to start tallying things up before determining if she has to put anything back.

At 77, the Queens, New York, resident lives frugally but comfortably on her monthly Social Security benefit, a bit of retirement savings and a small pension. That nest egg did not come easily.

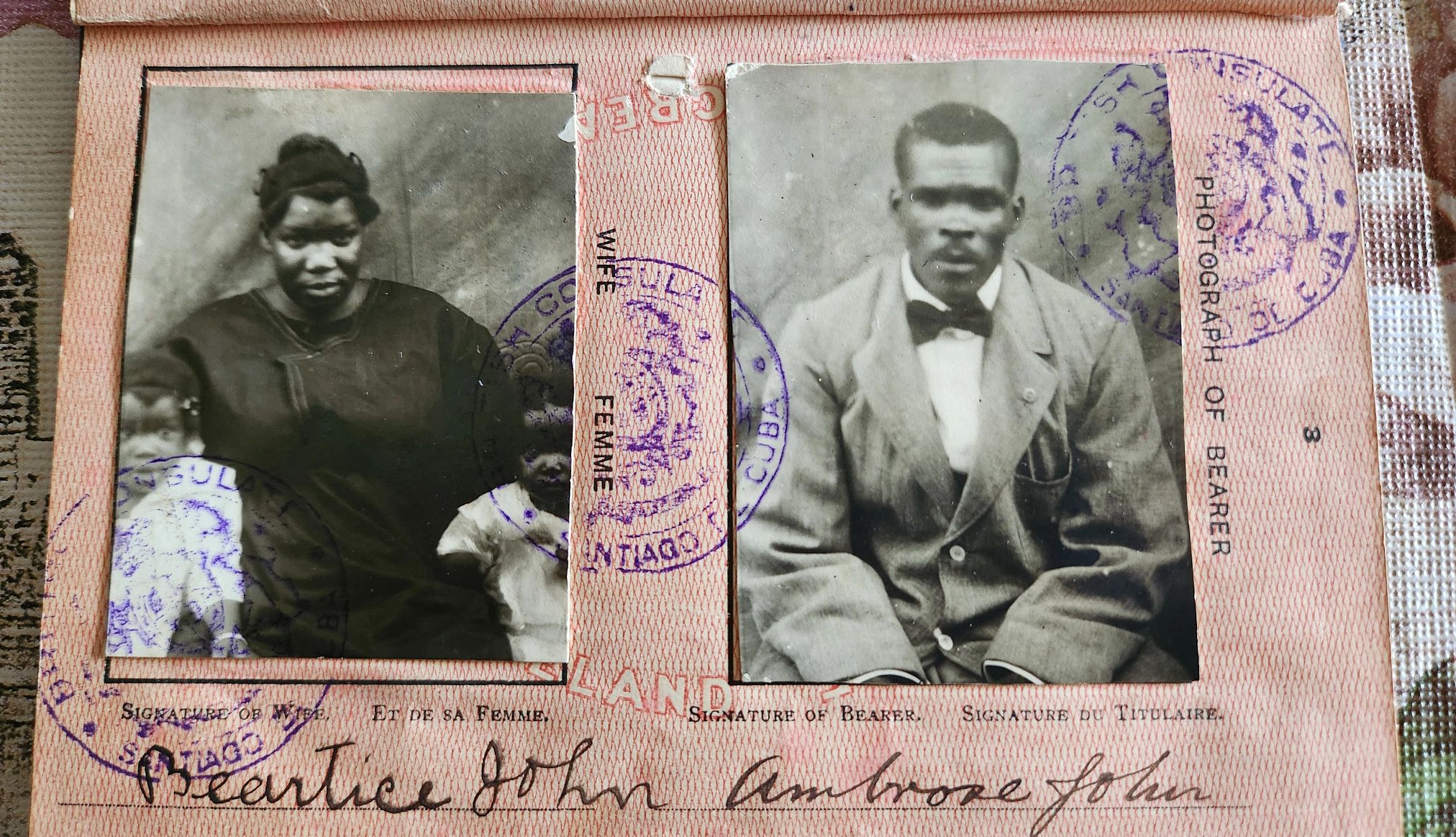

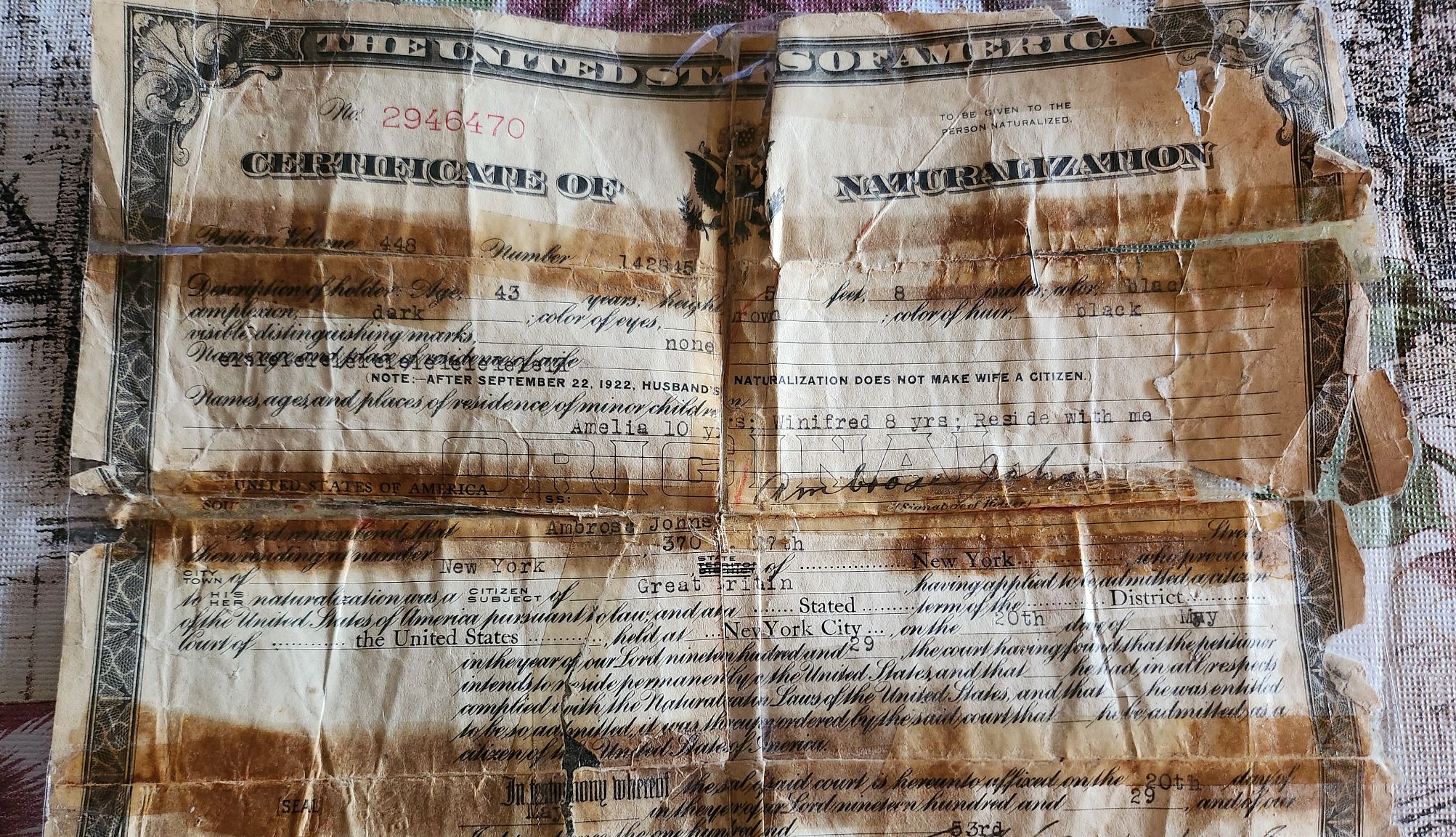

“I had to work very hard for it,” says Bermudez, whose grandfather, a native of Grenada, immigrated to the U.S. after working on the Panama Canal. She spent 45 years as an assistant to several doctors in New York hospitals, transcribing medical reports and doctors’ notes, among other tasks.

“Working in this country, especially as a Black woman, you had to fight your way to get certain positions,” she says. She took evening courses in writing and medical terminology to advance her career, balancing her job with her duties as a single mother.

Now, when her monthly payment arrives, it’s a reminder of how she was able to overcome those obstacles, just like her parents and grandparents before her, and build a good life for herself and her daughter.

This Aug. 14 will mark the 90th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of the Social Security Act, establishing a program that has helped generations of Americans like Phyllis Bermudez live with dignity in retirement.

“It’s a program with decades of success of lifting people out of poverty, particularly older adults,” says Kate Lang, director of federal income security at Justice in Aging, a nonprofit that fights poverty among older adults. “It’s got a great track record.”

Join Our Fight to Protect Social Security

You’ve worked hard and paid into Social Security with every paycheck. Here’s what you can do to help keep Social Security strong:

- Add your name and pledge to protect Social Security.

- Find out how AARP is fighting to keep Social Security strong.

- Get expert advice on Social Security benefits and answers to common questions.

- AARP is your fierce defender on the issues that matter to people 50-plus. Become a member or renew your membership today.

‘If we work hard, we should get something in return’

Indeed, Social Security keeps more Americans out of poverty than any other program in the United States, according to research by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a research group in Washington, D.C. Without it, 22 million more adults and children would be living below the poverty line, the center said in a January 2025 report.

Social Security is particularly vital for older women and people of color, who often work low-wage jobs that don’t offer access to 401(k)s or other retirement savings options. “All of the money ... coming into their households needed to be spent on their immediate needs for food and shelter and health care,” Lang says, making it nearly impossible to save.

More From AARP

Social Security Empowers This Retiree

Financial stability and independent living found at 87

Support for Social Security Growing, Poll Finds

3 in 4 adults surveyed by AARP rate it as one of the most important government programs

How Social Security and Medicare Changed Aging

Historic programs transformed the financial and health care landscape for older Americans