AARP Hearing Center

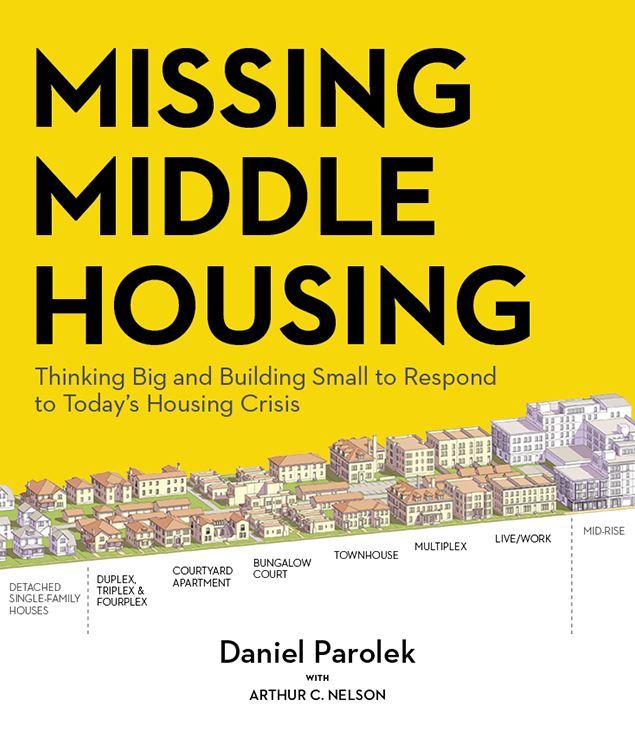

Adapted from Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis, by Daniel Parolek (Island Press, 2020)

Many of the neighborhoods that have Missing Middle types were built prior to the advent of zoning in the early 1900s. The common approach to zoning (often called Euclidean zoning) was created to separate uses and different housing types, such as single family and multifamily.

Housing Options

“Cities across the country are struggling with the lack of affordable housing, while development pressures are delivering McMansions or other inappropriately scaled housing, and NIMBYs (not in my backyard) are pushing back strongly against any housing that is not single-family detached.”

— Daniel Parolek

Zoning varies from city to city, but few zoning codes effectively enable Missing Middle Housing.

Efforts from city and state legislators are targeting much-needed changes to remove the types of planning and zoning barriers that prevent the creation of Missing Middle Housing.

For instance, in 2019, Minneapolis, Minnesota, approved a comprehensive-plan policy that will allow up to three units on any lot in the city, including those zoned single-family. That same year, Oregon passed legislation to allow three to four units on any lot in the state, depending on the size of the jurisdiction.

Following are some of the obstacles that keep communities from creating Missing Middle Housing.

1. In many instances, a city’s entire group of zoning districts jumps from single-family zoning, which may allow duplexes, to districts that allow buildings that are much taller and larger than the Missing Middle types

2. Very few multifamily or medium-density zones have the intent of delivering small-scale buildings with multiple units on small-to-medium-sized lots. Most of them assume multi-unit buildings are going to be big buildings on bigger lots.

3. Just about every community in the United States has mapped single-family zones on a majority of its land, thus prohibiting any other housing type in most of the city or county. According to a 2019 article in The New York Times, “It is illegal on 75 percent of the residential land in many American cities to build anything other than a detached single-family home.” And often the small percentage of land zoned for multifamily housing is in non-walkable locations that are far from ideal for the application of Missing Middle and other non-single-family housing types.

Missing Middle Reading

"The reality in most cities is that their planning and regulatory systems are barriers to delivering the housing choices that communities need. Density- and use-based planning and zoning were established to separate uses and create suburban environments, which makes it difficult, or impossible, to mix forms, uses, and types that result in walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods similar to the ones that formed organically before zoning was commonplace in the United States before the 1940s." — Daniel Parolek

4. Smaller residences (generally 600 to 1,000 square feet) enable a household to buy a smaller unit, build equity and then buy a larger home when needed. A system based on allowed density — either dwelling units per acre, or square footage required for each unit —encourages developers to build units as large and as expensive as the market will accept.

5. Off-street parking requirements have a tremendous impact on the financial and physical feasibility of Missing Middle Housing. In most instances requiring more than one parking space per unit, with no guest parking, is a barrier. Ideally, parking requirements will be removed completely, allowing the market to determine the amount of parking needed or not.

6. Impact fees are paid by the developers of new developments to a municipality to provide new or expanded public facilities (such as roads, sewers, schools, fire and emergency response). The fee charged for a unit is typically the same regardless of whether it is 5,000 square feet or 500 square feet. The high fee that can be absorbed by the sale or rent generated from a larger unit often cannot be absorbed by a smaller unit.

7. Neighborhood opposition prevents many developers from even considering building in communities with zoning that requires a public, negotiated process such as a use permit or a rezoning. The irony is that the unintended consequence of this type of pushback is that larger projects are incentivized because they are the only ones that have the funding and the tolerance to risk making it through the process

8. Currently there is not a single large-scale builder that is focused on delivering Missing Middle Housing types like there are for single-family homes and larger multifamily housing. The primary reason is likely that these types have been illegal under most city’s zoning codes for three to four decades, so there was no reason for an industry to exist.

9. Industries and professional organizations need to adapt and focus on Missing Middle Housing, much as they did in the early 2000s to deliver vertical mixed-use projects. Various groups within the housing industry are trying to position this conversation with builders, but the response has been slow.

10. Building larger buildings, say a 125 to 150 unit apartment or condo building, provides easier-to-identify and often larger cost efficiencies than building a four-, eight-, or even a 16-unit building or series of these buildings. Builders and developers who are looking for higher returns on their investments are not building Missing Middle types.

11. When a for-sale residential project requires shared maintenance, shared outdoor space, or other amenities that are provided to owners, a condominium association or a homeowners association is established to manage the maintenance and to collect monthly fees to help pay for this maintenance. For smaller projects, the cost and complexity of setting up such systems can impact financial feasibility and be too intimidating for smaller, less-experienced builders.

12. Any residential building with four units or more triggers Fair Housing Act requirements. These are defined as a barrier primarily because they add additional cost and complexity that can make it difficult for small builders. That said, fair housing requirements are important for providing housing choices for people with special needs and housing for the nation’s rapidly aging population. A good architect is accustomed to working within the act’s parameters and can deliver a great design while meeting the standards. (A related regulatory complexity is the International Building Code, which applies to any residence containing more than two units.)

Page published July 2020

Learn More

- Book Excerpt: The 'Missing' Affordable Housing Solution

- Slideshow: Missing Middle Housing Types

- Web Page: AARP Livable Communities: Missing Middle Housing

More from AARP.org/Livable

Use the dropdown to choose a livability topic.