AARP Hearing Center

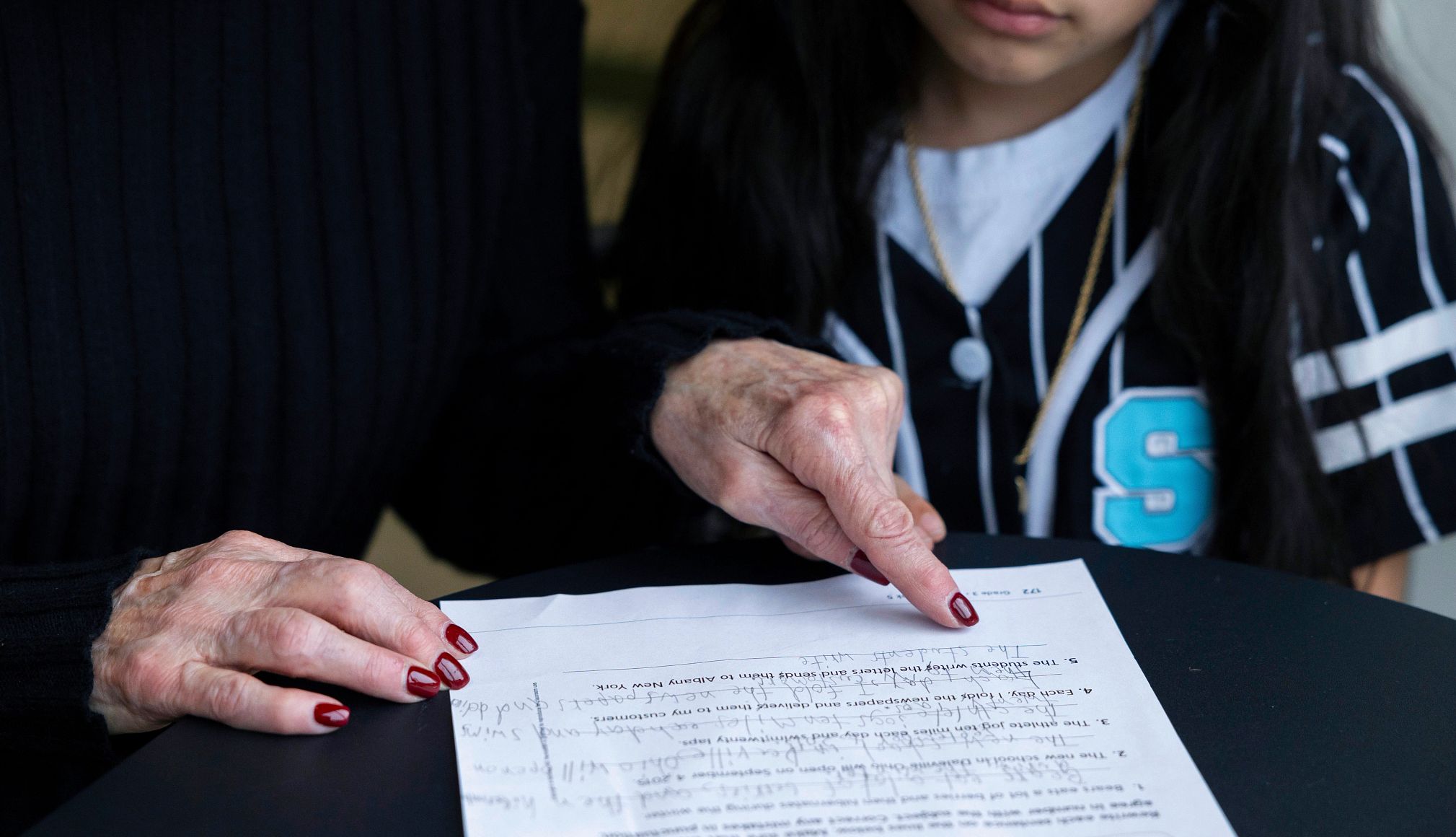

Two days a week, Janice Magri volunteers as a teacher’s aide for the third graders at Goodnoe Elementary in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. She files tests and homework sheets for the teacher, does crafts with the kids and makes sure to spend time with the children who need extra help with schoolwork.

Magri, 81, says it’s difficult to remember what it was like to be 8 years old, but mentoring children that age through S.A.G.E. helps her understand their experiences growing up during “a totally different time” and empathize with the needs of the greater community. S.A.G.E. (Senior Adults for Greater Education) connects adults 55 and older with volunteer mentoring opportunities in some Pennsylvania school districts. It’s one of thousands of mentorship programs nationwide that help people in their later years find ways to help younger generations.

Mentoring is a win-win, Magri says — benefiting both mentor and mentee.

“I think seniors shouldn’t be afraid to step out of their comfort zone … or think that you don’t have anything to offer. Seniors have a lot to offer. We’ve experienced a lot of life,” says Magri, who has been mentoring with S.A.G.E. for eight years. “I’m contributing, and it makes me feel very, very good about myself.”

Here’s why you should consider mentoring and how to get started.

Why be a mentor?

It helps you find purpose. It’s common for retirees to go through a loss of identity after exiting the workforce, says Nancy Schlossberg, 94, a retired professor of counseling and author who specializes in life transitions, living in Sarasota, Florida. People need a reason to get up in the morning and to get through the days, months and years after retirement.

That’s what mentoring does for Magri, who lives by herself.

“When I retired, I didn’t know what I was going to do,” she says. “As far as I’m concerned, it was up to me to find things to do to keep myself occupied and not complain to my children that I don’t have anything to do.”

She says she looks forward to the days she gets to mentor in the classroom. “I can’t wait. It gets me out.”

It’s also a way to get over the loss of a partner — something many retirees go through, says Nancy Larger, the partnerships manager for Big Brothers Big Sisters of Tampa Bay.

“A lot of our seniors move here with a spouse, and then the one spouse will pass,” Larger says. Many survivors feel lonely and without purpose, but mentoring “breathes new life into them” when they realize “how much they have to offer a child,” Larger says.

It keeps them physically and mentally active.

Magri says she’s constantly learning new skills by working with children in the classroom and helping the teacher. (And she’s surprised by the high-level math they learn at such an early age.)

More From AARP

How to Stop Languishing and Start Flourishing

A new book offers ways to ‘feel alive again’ when you’re feeling empty and world-weary

9 Essentials for a Happier Life, According to Oprah Winfrey

Her new book ‘Build the Life You Want’ with Arthur C. Brooks offers an action plan for ‘happierness’

How to Find a Mentor for Your Small Business

Connecting and networking with experienced advisers can help your business grow

Recommended for You