AARP Hearing Center

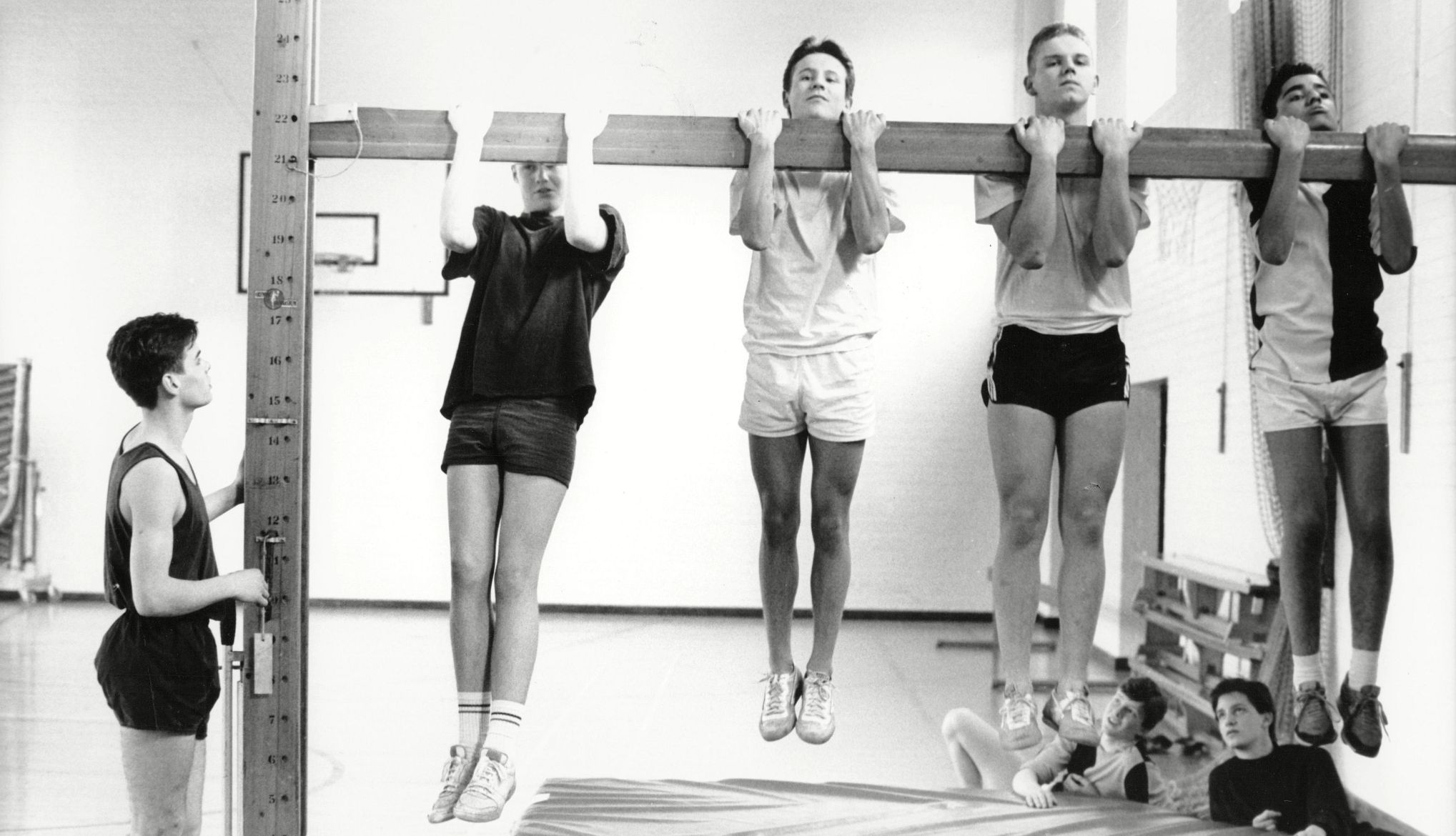

On Thursday, President Trump signed an executive order to bring back the Presidential Fitness Test, that rite of passage best remembered for humiliating an entire generation in mesh shorts. The move, according to the White House, is part of an effort to “restore urgency in improving the health of all Americans.” It’s unclear exactly which exercises will be included in this reboot — the original test went through many iterations — but the symbolism is clear: The country, once again, is being told to drop and give twenty.

If the news sounds like a time warp, it’s because the test has always seemed like a strange blend of patriotism, public health and performative sweat.

The program was introduced at the height of the Cold War, after years of hand-wringing over the physical fitness of American youth. That anxiety was sparked by a 1950s study by Hans Kraus and Sonja Weber which found that American children lagged far behind their European counterparts on basic strength and flexibility measures. Kraus and Weber’s dire conclusions landed them an invitation to the White House. By 1956, President Eisenhower had signed an executive order. Two years later, a national “test battery” was rolled out.

The exercises changed slightly over the years — straight-leg sit-ups gave way to bent-knee versions, and the infamous softball throw was mercifully axed in 1976 — but the basic idea endured. In 2012, the Obama administration replaced the test with the Presidential Youth Fitness Program, a gentler approach that emphasized personal progress over national percentile rankings. Critics of the old model had long argued that its rigid scoring penalized children who matured later or had different body types — and, perhaps worse, turned gym class into a stage for public failure.

Most people who grew up with the test have unpleasant recollections of it.

“Ugh, the rope test,” my wife said, refusing to believe me when I gently informed her that the official test did not include any rope climbing.

My own memories are less haunted. As a 10-year-old, I won the Presidential Physical Fitness Award — meaning I hit the 85th percentile of performance across its half-dozen exercises. I remember receiving the certificate — thick, creamy paper stock with a sort of odd, Lord of the Rings typeface and signed “Jimmy Carter, President of the United States” — and an embroidered patch featuring a fearsome gold eagle. Both went on a shelf, displayed proudly next to a beer can collection.

Thinking back on my youthful achievement, I wondered how I would stack up at age 55. Although Trump’s executive order did not specify the framework of the test, its fundamentals have remained largely unchanged throughout the years.

It’s a tough comparison to make, largely because it’s hard to find reliable data on, say, sit-up performance among the middle-aged; rather, we often start getting lumped into the early cohort in studies of senior-oriented fitness batteries like the “chair stand test” (i.e., how often can you rise out of a chair in 30 seconds).

I am a fairly fit person. I ride a bike three or four times a week and play a weekly “old man” soccer game. But I do these things for fun, not as part of any training regimen. Push-ups and pull-ups do not strike me as fun, hence I do not do them.

I have also been recovering from a torn hamstring, picked up by unwisely adding a second soccer game to my weekly schedule. My general philosophy is “Play hard, eat often.”

So I headed to the local high school track, accompanied by my 14-year-old daughter, who served as test proctor. To at least place on par, I’d have to hit these marks:

You Might Also Like

What Can I Do to Ease Leg Cramps?

Cramps are common in older adults. Here’s why they happen — and how to treat them

Raise Your Walking Pace Safely

Why adding just a few steps to your walking pace can offer health benefits.

#1 Exercise for Your Knees

Try this to strengthen the muscles that support your knees