AARP Hearing Center

Donna Lulay, a retired educator, had open-heart surgery in 2007 to replace her aortic valve due to a genetic heart valve defect, and in 2023 needed surgery to replace the valve again. The procedures were a success despite one not so uncommon complication: After the second surgery, her heartbeat was slower than it should be, putting her at risk for serious health complications.

Lulay, now 66, was told she needed a pacemaker to help regulate it.

“I was so upset,” says Lulay, an avid hiker, skier, walker and all-around active individual who also happens to be my first cousin. “Getting a pacemaker when it was unexpected was a shock.” But now, almost a year later, Lulay is back to exercising and traveling, and says she feels “more confident” not having to worry about her heart functioning properly.

Here are five things to know about pacemakers and how they work.

1. Roughly 3 million Americans are living with a pacemaker.

Lulay is one of nearly 3 million people in the U.S. who has a pacemaker, a small battery-powered device that prevents the heart from beating too slowly. Terminator actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, 76, is another

Most people with pacemakers — more than 70 percent — are 65 or older, according to Yale Medicine.

2. People with abnormal rhythms may need a pacemaker.

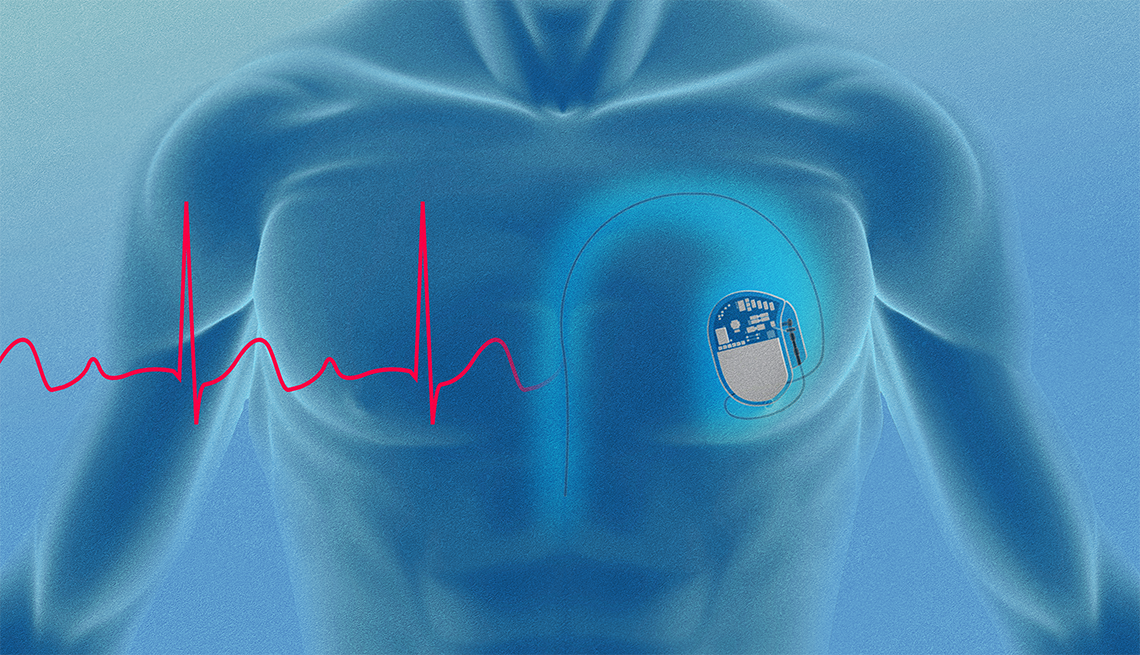

There are several types of cardiac devices that can be implanted, or placed under the skin just below the collarbone with wires leading to the heart. A pacemaker is one of them.

It’s needed when the heart doesn’t beat normally — it may be too slow or the electrical signals that control the heartbeat are disrupted.

The device consists of a generator with a battery that provides the electrical impulse for the heart to beat, sensors (electrodes) and wires (leads) that deliver the electrical impulse to the heart muscle. The pacemaker monitors the heart’s rhythm and if it detects certain abnormalities, it will generate an electric impulse so the heart can beat with a normal rhythm.

For many patients, a pacemaker works only when needed — if the heartbeat gets too slow, it will jump in and correct it. However, some people are considered “pacemaker dependent” and rely on the device to constantly regulate the heartbeat.

You may need a pacemaker if you have an abnormal heart rhythm that is considered serious and is not expected to go away on its own or with other treatment. You may also need one if a less serious rhythm issue causes symptoms such as lightheadedness or fainting, or prevents you from doing your day-to-day activities.

Common reasons that pacemakers are placed include:

- Sinus node dysfunction: The sinus node is specialized heart tissue in the right atrium that initiates the electrical impulse for your heart to beat.

- High-grade block: when a section of the heart’s conduction system does not transmit the electrical signal, for example at the atrioventricular (AV) node that sits between the upper and lower heart chambers.

- Fainting due to abnormal heart rhythms.

- Damage to the heart’s conduction system after procedures such as open-heart surgery or having an aortic valve replaced using a catheter.

There are several tests that your doctor can perform to determine if a pacemaker is right for you.

More on Health

Medical Advancements in Cardiovascular Disease

New research is changing the future for older Americans' heart health

Want to Live Longer? Take the Stairs

New study finds benefits to heart, blood sugar19 Heart-Smart Choices to Make Throughout Your Day

Treat your heart right morning, noon and night with these easy, research-proven, expert-endorsed ideas

Recommended for You