AARP Hearing Center

Joining my newly retired friends for dinner over several months, I began to notice happy hour becoming both earlier and more indulgent. Predinner drinks flowed into wine with our meal, followed by after-dinner pours.

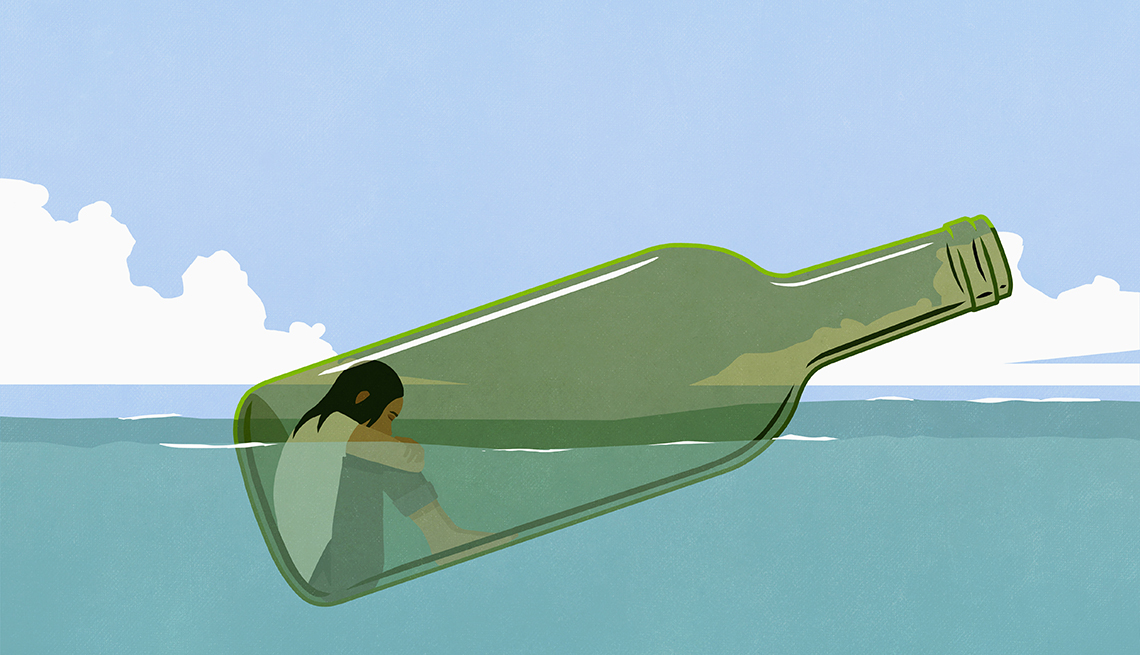

During those same months, I observed my friend was spiraling down from her infrequent “blue” moods to much more serious and pervasive “down” moods. “I need help,” she confessed one day over lunch. “I can’t shake this. I’m depressed.”

The depression and alcohol connection

It’s not unusual for low spirits to accompany heavy alcohol use. In fact, research shows that anxiety and mood disorders commonly co-occur with alcohol use disorder, and depression is the most common among them.

Among people with major depressive disorder, the co-occurrence of AUD ranges from 27 to 40 percent over a lifetime, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

What is alcohol use disorder?

AUD is a medical condition “characterized by an impaired ability to stop or control alcohol use despite adverse social, occupational or health consequences,” according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. It can be mild, moderate or severe. Binge drinking and heavy alcohol use can increase an individual's risk of alcohol use disorder.

Source: NIAAA

But which comes first?

There’s debate among experts who study the subject. For some, depression hits first and drinking becomes a way to self-medicate. For others, drinking triggers depression.

Whichever comes first, Patrick Fehling, M.D., an addiction psychiatrist at the UCHealth Center for Dependency, Addiction and Rehabilitation in Aurora, Colorado, believes “the real problem is drinking.” And the more a person drinks, research suggests, the more likely they are to develop depression.