AARP Hearing Center

In April 2010, Peggy Lillis, then 56, underwent a root canal procedure, and the dentist prescribed clindamycin, an antibiotic, for a suspected abscess. Soon after, she came down with what she thought was a stomach virus. The illness progressed to the point of her being rushed to the hospital. Turns out, she had C. diff, an antibiotic-induced bacterial infection of the large intestine that causes difficult-to-treat diarrhea and colitis, which is an inflammation of the colon. Lillis was admitted, diagnosed with sepsis, and died the following day.

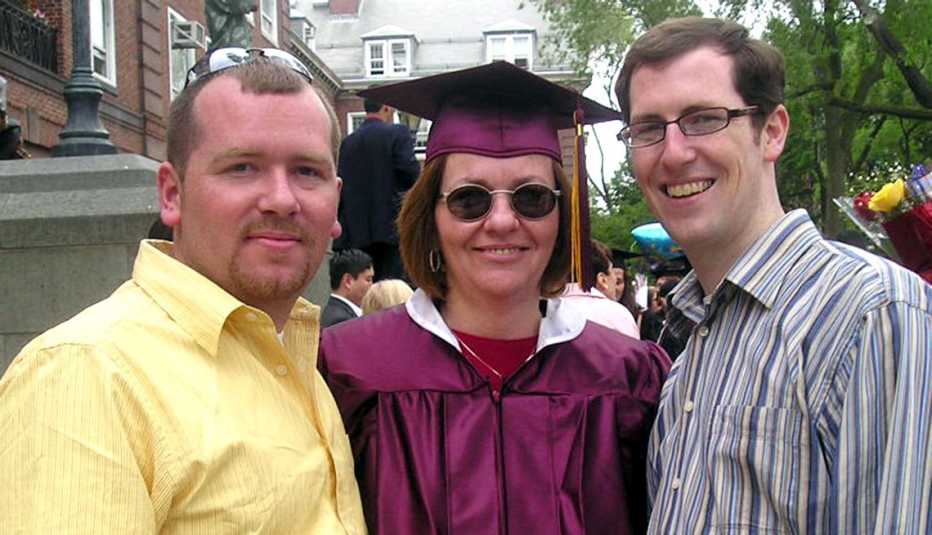

“My mother was so strong and full of life, but this superbug came along and took her in just six days,” says Christian John Lillis, cofounder with his brother, Liam, of the Peggy Lillis Foundation, a nonprofit created to educate the public and health professionals about C. diff and to advocate for better prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

The website for the foundation created in Peggy Lillis’ name is filled with the personal stories of both C. diff survivors and those who didn’t survive. The collection features women and men of different races, ages ranging from 5 months to 90-plus, and illness durations from a few weeks to more than a decade or “ongoing.” The narratives provide details about acquiring C. diff in a health care setting (commonly referred to as “hospital-acquired” or “long-term care facility–acquired”) or from antibiotic use (the shorthand for which is “community-acquired”). The antibiotics ciprofloxacin, clindamycin and various cephalosporins are among those that often appear in the personal dramas.

What heals you can make you sicker

Although antibiotics are healing and lifesaving, they can, at times, do damage by killing off the good gut bacteria that keep our GI systems working as they should. Once that happens, the C. difficile bacterium, which is generally present in our bodies as inactive spores, grows and takes over.

A special report published in June 2022 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that high levels of antibiotic prescription use put patients at risk for antibiotic-resistant infections, including C. diff, that are difficult to treat. Rochelle P. Walensky, M.D., the director of the CDC, writes that “more than 3 million Americans acquire an antimicrobial-resistant infection or Clostridioides difficile infections (often associated with taking antimicrobials) each year.”

The CDC categorizes C. diff as an “Urgent Threat.” According to “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States,” a 2019 CDC report, “nearly 223,900 people in the United States required hospital care for C. difficile and at least 12,800 died in 2017.” More than 80 percent of the deaths associated with C. diff occurred among Americans age 65 or older, with 1 of every 11 older patients dying within 30 days of diagnosis.

Since C. diff is contagious, it is easily spread in health care settings such as hospitals or nursing homes, often due to poor hygiene and the susceptibility of immune-compromised patients. But, as noted by medical journal The Lancet in May 2022, although hospital-acquired cases of C. diff decreased in the United States between 2011 and 2017, community-acquired cases have been increasing among children and adults younger than 65 years old.

In many cases, the simple instruction from a doctor to use a probiotic while taking antibiotics could make the difference. Better treatments are needed, and according to scientists who participated in the National C. diff Advocates Summit, hosted in May 2022 by the Peggy Lillis Foundation, several promising cures are in the works.