AARP Hearing Center

When women get mammogram results they would also get information about the density of their breast tissue under a new proposal from the Food and Drug Administration, the first change to federal mammography standards in 20 years.

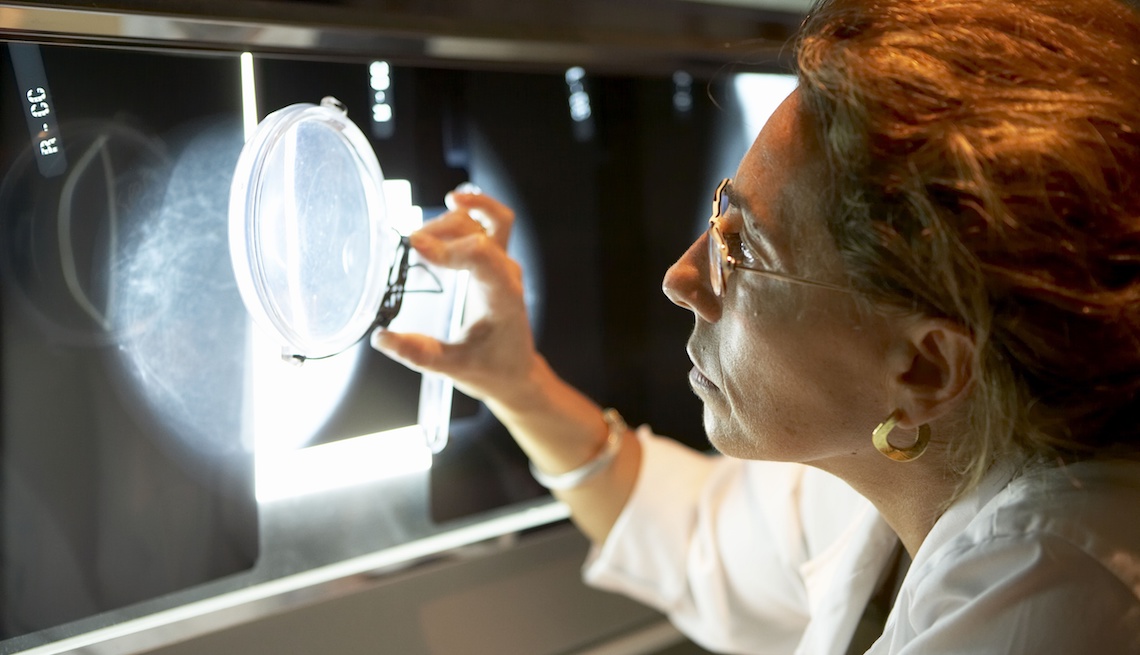

Because dense breast tissue can mask the presence of cancer (both appear white on a mammogram), getting information about breast density would be “basically notifying patients that it is not a perfect test,” says radiologist Sarah M. Friedewald, chief of breast imaging at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. The FDA wants the letters to also note that it’s harder to spot cancer in dense breasts.

About half of all women have dense breast tissue. Although dense breasts are more common in younger women, says Deborah Rhodes, an internist and breast cancer researcher at the Mayo Clinic, “some women retain it well into their 70s and 80s.”

Density is measured in four levels, from category A (“fatty,” or not dense) to D (extremely dense), with levels C and D both considered dense. Mammography’s ability to distinguish cancer ranges from about 57 percent sensitive in women who have extremely dense breast tissue to about 93 percent sensitive in women who have fatty breast tissue, says Friedewald.

The average risk of developing breast cancer for a woman in the U.S. is 12 percent; 268,600 cases will be diagnosed this year, according to the American Cancer Society. Its latest guidelines recommend that women at average risk begin annual mammograms at age 45, then switch to every other year at age 55. It's still considered the best test for breast cancer screening.

Thirty-seven states already have density reporting requirements on their books, but this proposal — a modification of the FDA’s Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992 — would standardize it across the country. The proposal is up for public comment through June 26.

For expert tips to help feel your best, get AARP’s monthly Health newsletter.