AARP Hearing Center

"Are we doing this today?"

It's 8:30 a.m. under blue skies in Santa Barbara, California, and Kevin Costner is giving me a dog head tilt at his front door. Someone obviously missed a memo somewhere (OK, so I've arrived exactly 24 hours too soon for our interview), and the Academy Award winner is doing his Oscar best to play it cool.

You're not supposed to test a movie star's patience this way. But Costner isn't the temperamental sort. At moments like these, it's reassuring to recall that he got his start in show business lugging cable and pushing a broom at a Hollywood studio not far from where he grew up in working-class L.A. He's a problem solver, a make-do sort of guy.

"Well, hold on," he says, as his brow unfurls and that eternally boyish grin curves into place. Next thing I know, he's fitting me into his day.

With more than four dozen credits in film and television, Costner at 59 can act on his feet like that. It's not just accommodating the unexpected guest. Like his characters in Dances With Wolves, Bull Durham, The Bodyguard and, more recently, TV's Hatfields & McCoys, for which he won an Emmy, Costner shifts easily between charming reserve and "Let's do this thing!" And he's someone who's game to take the odd dare. He has toured as a roots musician, opened an interpretive center on the American bison and invested millions toward the development of centrifuge devices that clean up oil spills.

He's also Lego-deep in round two of being a dad. After seeing his first four children safely into the double digits, Costner took a breath and had three more with his wife of 10 years, Christine Baumgartner, 40, a model and handbag designer. He looks amused as we stroll through their Japanese-influenced home, passing an entertainment den with wired gizmos that clearly baffle him. "I have never played a video game, so I'm not on Xbox," Costner says. "But I teach the kids about hunting and fishing, and we fight." He knows that sounds wrong. "The kids want to be wrestled," he says of daughter Grace, 4, and sons Hayes, 5, and Cayden, 7. "They want to be physical. I'm really kind of basic."

That's a curious statement from a man whose movies have grossed more than $2 billion worldwide and who owns 17 acres of prime beachfront here and 160 acres more in Aspen, Colorado. But as he opens up during a long, candid conversation about parenting, love, work and aging, it's obvious Costner values simplicity and time with family over the fanfare of fame, and will risk whatever it takes to make good on the things he believes in.

His latest gamble is Black or White, a film due out in January, in which he plays a recently widowed prominent Los Angeles attorney. The lawyer's string of hard circumstances had begun when his daughter, entangled with a drug dealer, died seven years earlier. In the aftermath, he and his wife took on the task of raising their biracial granddaughter on their own.

The film is a deeply felt project about race relations that reteams Costner with his friend Mike Binder, the writer-director who helped spark a career revival for the actor with The Upside of Anger in 2005. "Nobody likes to talk about race, and everybody finds it difficult," Costner says. "This platform is a jumping-off point for having this discussion."

Even with Costner's clout, Black or White was a bear to get made. The script languished in development for years, and when the studios refused to finance it, Costner opted to put in half the production costs from his own pocket, essentially to fulfill a promise to Binder to bring a meaningful movie to screens. "Kevin doesn't follow the crowd," Binder says. "And he's a genuine guy. Whenever someone might think, 'Oh, he's just a big movie star, and this is just a business thing,' he does something that says, 'Hey, I'm your buddy.' "

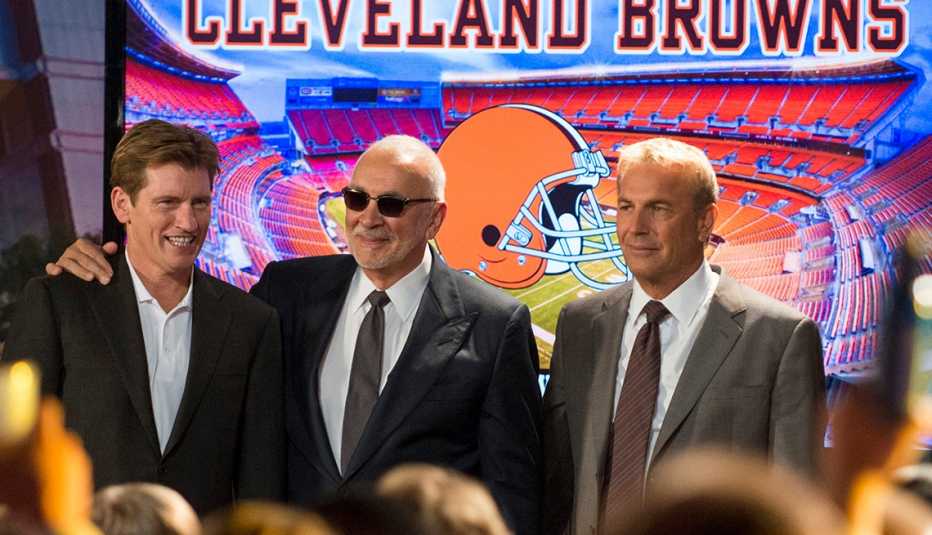

Ivan Reitman agrees. He directed Costner in last spring's Draft Day with good results and appreciated not just his solid character work as an emotionally distracted pro football general manager, but also his personal integrity as production hit typical snags and setbacks: "I think Kevin is a highly moral individual, and I never felt that he was pulling any kind of star stuff with me. He was very direct, very real and very gracious all the time. And he didn't go back on his word, ever."