AARP Hearing Center

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, 78, is a legend in the NBA, where he earned six championship rings and became the all-time leading scorer (since passed by LeBron James). But he’s had a rich life in the more than 35 years since his retirement from basketball. He’s devoted himself to — among many other things — writing, including his 2015 novel Mycroft Holmes, a mystery centered around Sherlock’s older brother (Abdul-Jabbar is a huge Sherlock Holmes fan).

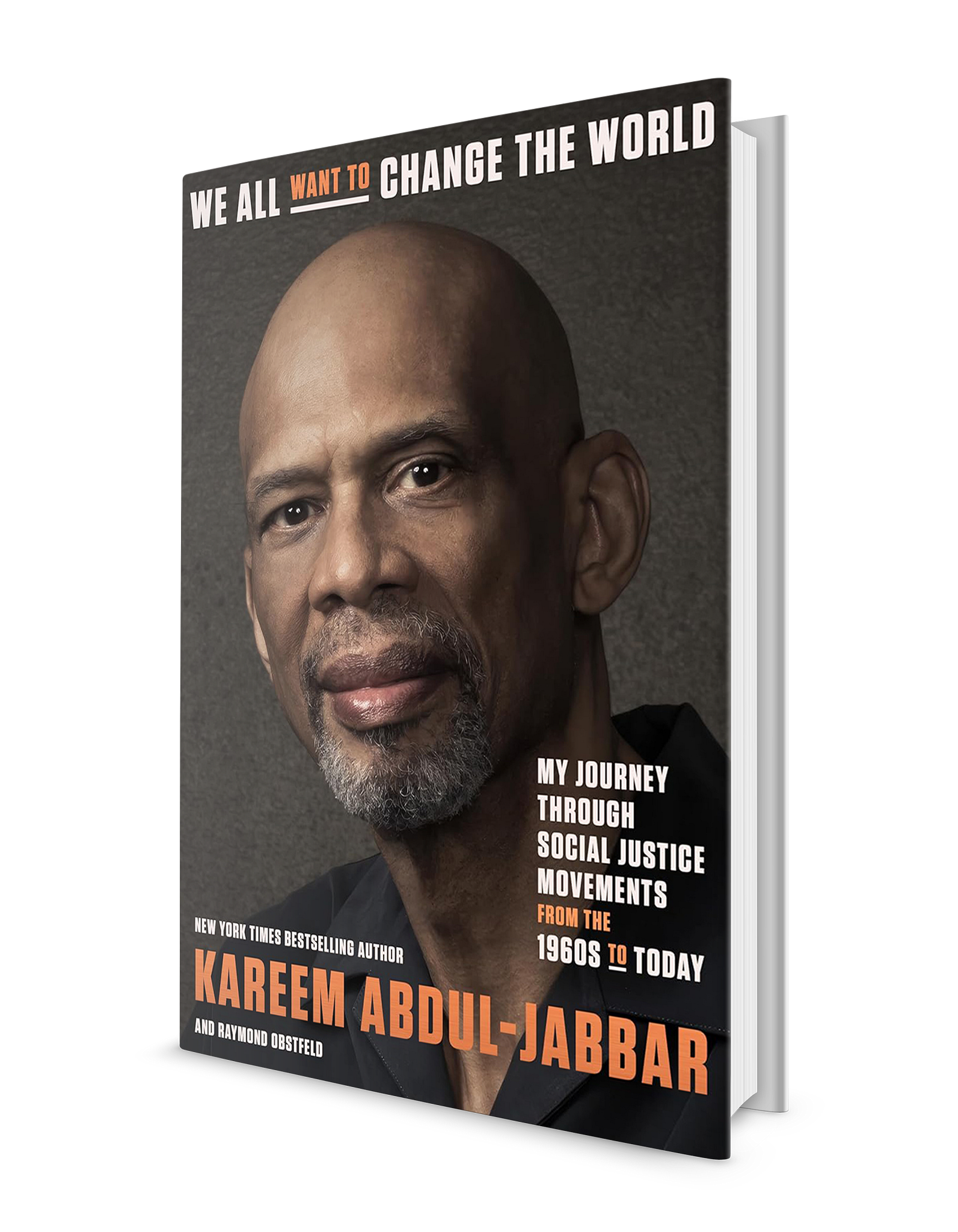

Abdul-Jabbar has also focused his efforts on social justice. His new book, We All Want to Change the World: My Journey Through Social Justice Movements From the 1960s to Today, is full of personal stories and lessons from the past that he believes can be applied to today’s injustices. Abdul-Jabbar recently spoke with AARP about this book, life after basketball and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In your new book, you describe two events in 1964, when you were 17. One was a Martin Luther King Jr. press conference you attended for a student publication. The other was a protest rally you attended in Harlem that turned violent. What did those experiences teach you about social justice?

At the time, the lessons were more emotional than intellectual. Meeting Dr. King made me feel like I was a part of the solution. He inspired hope and made me want to join him in his righteous crusade. In contrast, the protest scared the hope out of me, at least temporarily. There were real bullets flying, stores being looted, people running for their lives. This was the real world of civil rights protests, and it wasn’t soft-spoken like Dr. King. It screamed in my head. It made me aware of the fact that lives had been lost in the fight for social justice, and more lives were going to be lost before we got to our objective.

And that quest is still part of your life.

There is a quote that I related to: “Until all of us are free, none of us are free.” As I get older, I understand more and more what that means. A lot of people think [the fight for civil rights] was something that happened back in the ’50s and ’60s, and everything is OK now, but we’re still fighting the same fight. Some of the faces of the issues have changed, but at the heart of it, we’re still trying to live up to what Mr. [Thomas] Jefferson said about all people being created equal.

You’ve talked about how basketball helped shape your personal identity and social values. How so?

It gave me the determination and patience I needed to excel. When I was in the fifth grade, an older kid in the neighborhood showed me the George Mikan drill, which involved shooting a hook shot. That’s all I had. So I worked on it and worked on it, and by the time I got to the eighth grade, I was pretty good at it.

You Might Also Like

Preview: 44 of Spring’s Top Reads

Ocean Vuong, Isabel Allende, Deanna Raybourn, Ron Chernow, Dave Barry and more authors with 2025 releases

Mel Robbins on the Life-Changing Power of ‘Let Them’

The self-help guru talks to AARP about her bestselling book and why you’re never too old to reinvent yourself

10 Fantastic Short Story Collections for Your Book Club

A good story can give your group plenty to talk about