AARP Hearing Center

We asked Facebook AARP Family Caregivers Discussion Group members to submit pressing questions they’d like Barry Jacobs to tackle in his caregiving column. The family therapist and clinical psychologist took on this hot-button topic:

I’m feeling trapped. This time of my life should be my golden years. I am 66 years old — originally retired at 45 — but I went back to work part-time to get out of my house. My mother, who is 90, has lived with my husband and me for 8 years now. She has no income, only Social Security, which is why she is living with us. She tells me I owe her to take care of her — and maybe I do — she raised me. I'm tired, frustrated and I want a life.

(Letter edited for length and clarity.)

Barry Jacobs: Let’s first state what’s most obvious: You have been a very good daughter to your mom. She has been able to rely upon you for food, shelter, and company for eight years. If your mother isn’t giving you a great big pat on the back for that, then imagine all the readers of this column sending you their heartfelt encouragement and perhaps a gentle hug for all you are doing.

What is also obvious is that you are entitled to a life. Everyone is. Though many caregivers cite “giving back” as a prime motivator for taking care of a parent, daughterhood isn’t indentured servitude requiring total sacrifice. No matter what your mother may think you “owe” her, eight years is a long time to have her living in your home. It is a long time for you and your husband to give up your privacy. It is a long time to “feel trapped.”

Join Our Fight for Caregivers

Sign up to become part of AARP's online advocacy network and help family caregivers get the support they need.

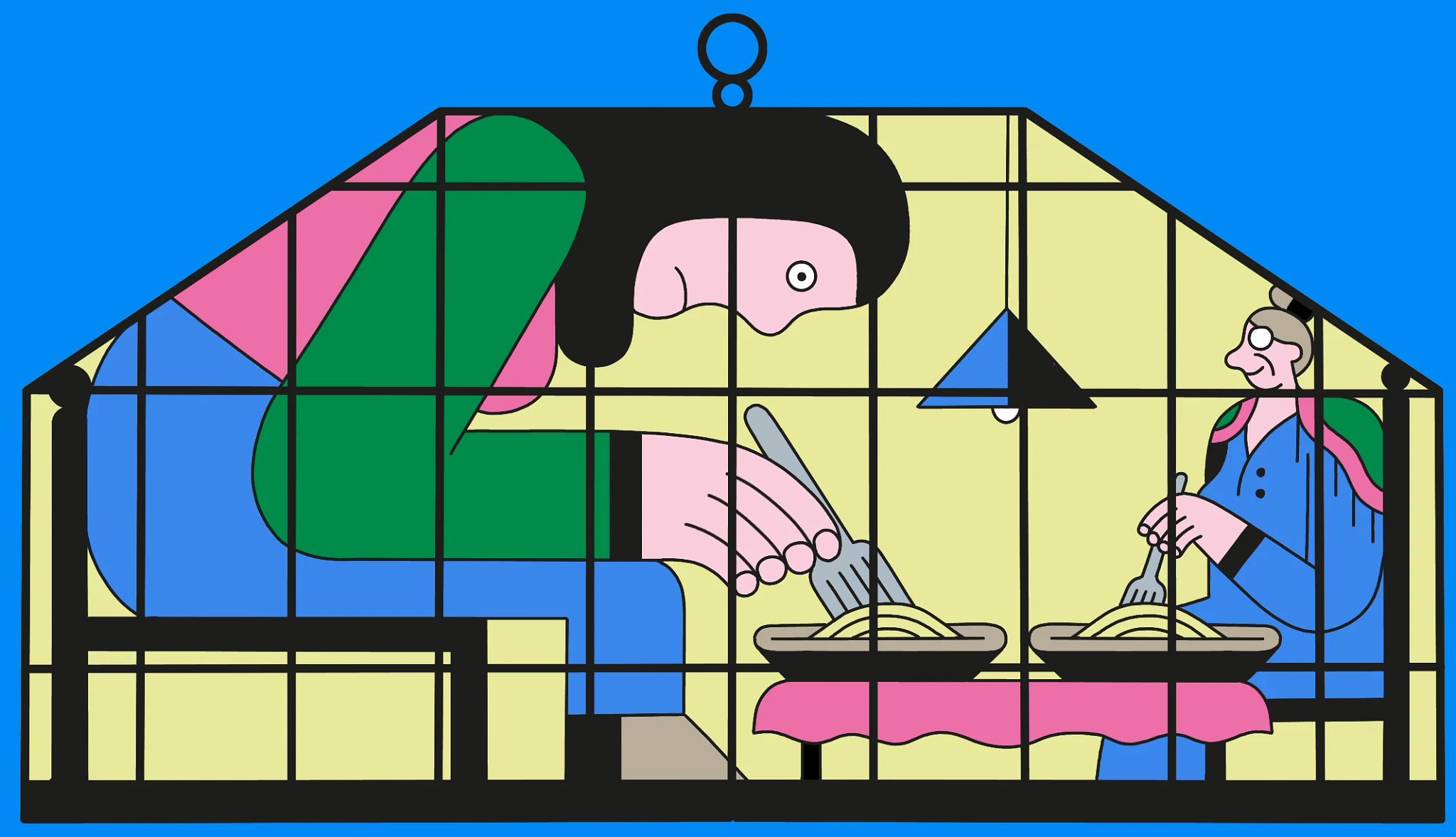

It is always disturbing to hear a caregiver say they “feel trapped.” It makes caregiving sound like a barred cage or a penal colony for criminal exiles. Both images miss the loving spirit at caregiving’s core. Yet it is not uncommon for caregivers to feel trapped. Why? In part, it happens whenever caregivers are burnt out, dreading each day’s drudgery and forced labor. It can also stem from when caregivers believe they have no choice about caregiving. That perceived lack of choice can be harmful to them.

More From AARP

The Staggering Financial Toll of Family Caregiving

Caring for an aging parent can be rewarding but also can drain your finances

Why We Should Normalize Therapy for Grieving Caregivers

Losing a partner can leave you feeling lonely, depressed and heartbroken. Don't go it alone10 Common Mistakes That Family Caregivers Make

Experts share how to avoid these caregiving pitfalls