AARP Hearing Center

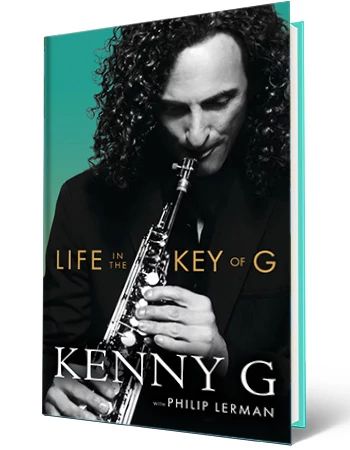

Musician Kenny G, 68, didn’t grow up dreaming of becoming the best-selling instrumentalist of all time. He tells AARP that 10-year-old Ken Gorelick “was just going to school and trying to get good grades. If I’m playing the saxophone, it was just to be good in the school band. It wasn’t because I heard somebody on YouTube and said, ‘Whoa, I want to be a superstar.’ ” He writes of his origin story and rise to fame in his memoir, Life in the Key of G, out Sept. 24, and in our interview, he reveals why he loves performing in his 60s, piloting his own plane and golfing with comedian buddies George Lopez, Ray Romano and Martin Short.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did you read any memoirs for inspiration before you began writing yours?

No. I did read a little bit of Matthew McConaughey’s book [Greenlights] because it came out as I was writing [mine]. And when I read it, I thought, OK, that’s really good. The way he talks and writes — how does he do that? So I didn’t want to read too much more of it, because then I was going to throw my book away. The way he writes it is almost like a preacher giving a sermon — he’s talented that way, charismatic. My book is not going to be like that. And if I tried to make it like that, it would just ruin everything. So that’s a good reason why I didn’t want to read other people’s memoirs. Just like with music, I actually don’t want to listen to a lot of music that people are doing today, because I don’t want to think, Oh, I should do a song like that. I just want to do a song like whatever I imagine is what I want to do, because that’s how you stay original.

You write about your surprise that musicians like Kanye West (now Ye) and The Weeknd have reached out to you. Who would you love to collaborate with?

If I could get [saxophonist] Grover Washington Jr. to be alive again, or Stan Getz. I made a duet with Stan Getz on one of my records from just using technology and just finding notes that he played. And I made him play a melody with me. It was pretty amazing. I’d be flattered if Wynton Marsalis called me, but I am so opposite. I don’t think that his world really likes my music, so that’s never gonna happen. Yo-Yo Ma coming to me — that would be really cool, or Lang Lang the keyboard player. I’m surprised [we haven’t] done a duet together, because we know each other very well and really like each other. He’s such a nice guy, and what a virtuoso! So doing something with him would be pretty special.

You’re also a licensed pilot. Where have you been flying lately?

Well, at the moment I haven’t flown for a year because my airplane got into an accident. And I wasn’t flying — it was sitting. It’s a float plane. So it was sitting on the water, and there was a storm, and a tree broke and flew in the wind and landed on my airplane. It broke the wing, and it broke the elevator. It broke a little bit of the tail. I was just going to pound out the dents. I said, “Well, I’ve got to get it off the water and get it to an airport.” So I took pictures and [sent them] to my friends that know a lot about it, and they wrote back in caps: “DO NOT FLY THIS PLANE.” I asked, “Well, what’s going to happen?” and they said, “The wing could fall off when you’re flying, and you’ll die. That could happen.” So I haven’t flown for a year, but normally, I probably [fly] once a week just to keep my chops.

You Might Also Like

Connie Chung Writes Revealing New Memoir, ‘Connie’

Journalist dishes on how she dealt with ‘the boys’ in the newsroom, the strain of marijuana named after her and more

Kathryn Hahn Is Loving Life as a Marvel Universe Witch

Actress shares the real-life superpower she’d love to possess and how she feels about aging in Hollywood

Drew Carey Loves ‘Everything’ About Hosting ‘The Price Is Right’

Game show host shares advice from Bob Barker and why he advocates for mental health awareness

Recommended for You