AARP Hearing Center

Chapter 13

Saturday, May 28, 2016

IN THE MORNING, I FIND MYSELF a quiet table in the hotel’s dining room and spread out my notes and laptop and a piece of paper on which I’ve written “Erin.”

When I first joined Suffolk County Homicide, I worked under a guy named Len Giacomo. He was a legend in the Suffolk County P.D., and by the time I met him, he’d solved more cases and had more convictions under his belt than anyone who’d ever worked homicide on Long Island. Len was a true intellectual; he liked opera and modernist literature and wine and he and his wife traveled a ton, to Rome and Thailand and Guatemala, and any topic of conversation that came up, Len had something to say about it. But he wasn’t showy, and when I look back at how he worked, it was the fact that he was completely unbiased that was probably his greatest asset. He’d go into a case with an absolutely open mind; he told me once that he had a strategy for this, a meditation technique he’d learned on an ashram in India. He would write the victim’s name in the center of a piece of paper and as the case went on, he would slowly add pertinent information to the paper, with everyone he met surrounding the victim so he could see the relationships, the dynamics.

He taught me this technique when we were working a domestic homicide case together, and over the years I’ve refined it for my own purposes.

I start by writing in “Emer Nolan” and “Daisy Nugent” up at the top. I can’t find anything on Daisy, but a few minutes of Googling Emer’s name turns up the software company Roly mentioned. Under “About Us” there’s a picture of Emer and a biography and email. I send her a message, saying that I’m in town and I’d love to see her, just to catch up. Then I go back to my diagram. I write in “Conor Kearney,” “Hackman O’Hanrahan Jr.,” and “Niall Deasey.” Then I add in “other girls at the café,” “neighbors,” and “Jessica, Chris, Lisa, Brian,” and, because Len taught me well, I write in my own name and Uncle Danny’s and my dad’s, too. Everyone in her orbit. We were all in her orbit.

I’m about to put the paper away when I think of another Len lesson. Don’t get ahead of yourself. I make a little circle at the bottom of the paper and write “?” The unknown person, the man I’ve come to think of as the gray shadow. Who is he?

Back in my room, I turn on the television and catch the noon news. There’s a short update on the Niamh Horrigan case. It sounds like they’re still searching the hills and doing door-to-doors in the area. The Army Reserve is helping, along with various mountain rescue and hiking groups. Niamh’s parents have offered a ten thousand–euro reward for information leading to her safe return. That’s what they talk about on the television. What they don’t talk about is everything else that’s going on, the interviews that Galway police must be doing with anyone who ever knew Niamh, the frantic scouring of sex offender databases, the tearing apart of every social media account or electronic device Niamh’s ever used.

“Niamh has been missing for a week now and her family and friends are starting to ask the Gardaí why there has been so little progress on finding her. The Gardaí say every measure is being taken to locate Niamh, but given the fates of the other women who have disappeared under similar circumstances, the family feels time is growing short to find Niamh safe and well,” the announcer says.

“In a related development, the cousin of Erin Flaherty, the American student who disappeared in 1993 and is widely believed to be the first victim of the so-called Southeast Killer, has arrived in Dublin as the Gardaí examine the remains discovered in Wicklow this week to determine if they are Flaherty’s.”

My cell rings and I switch off the television. It’s Roly. I can hear that there’s something as soon as he says, “D’arcy? Where are you?”

“At the hotel. What? Have you identified her? Is it Erin?”

I know from the way he hesitates. I can feel the hotel room shrinking around me. My vision narrows. I take a deep breath.

“It’s more complicated than that,” he says. “It’s not Erin. But they found something with the remains. Something of hers.”

***

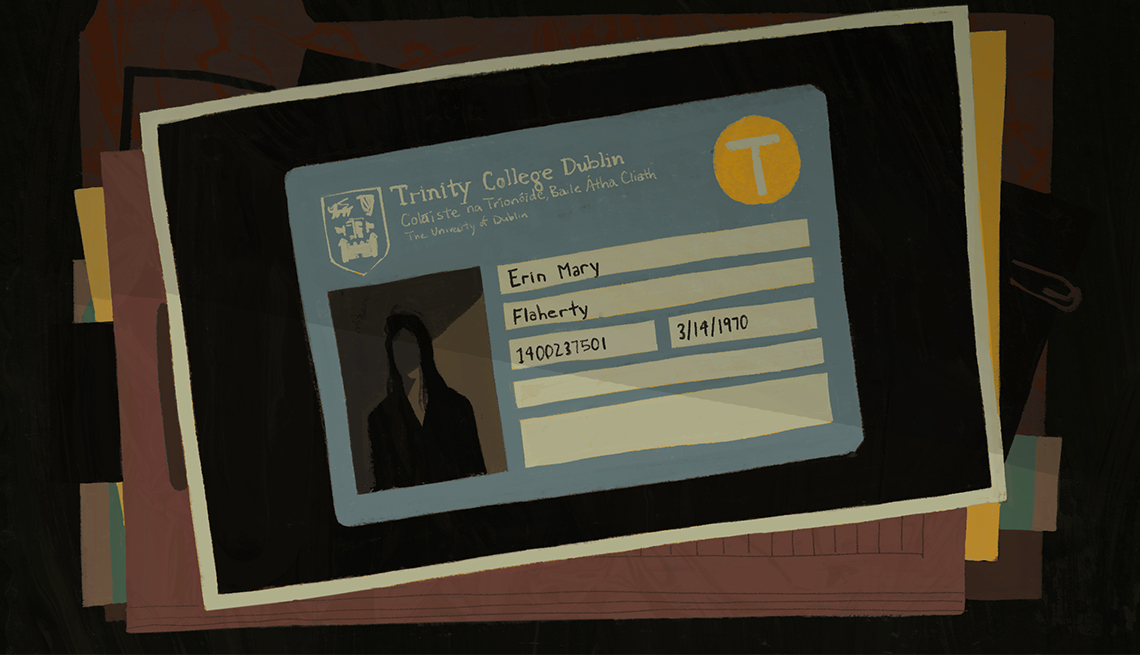

What they found is a student ID card from the year Erin had spent as a student at C.W. Post. It’s laminated, which is why it’s held up all this time. Roly meets me in the hotel lobby and takes me into the bar to show me a photograph of the card.

Erin Mary Flaherty, it reads. DOB 3/14/1970. The photograph is a little cloudy, but I remember the frosted pink lipstick she liked to wear. She has on the leather jacket; I can just see the collar and top button in the photo. I nod. It’s hers. As if there’s any doubt.

“But who is it? Whose remains are they?” I’m practically shouting at him. “If it’s not her, Roly, who is it? And how did the ID and the scarf get in there with her?”

He glances over at me. His eyes are lined. He looks about a hundred years old. “I’m heading over to talk to the state pathologist. We hope she’ll be able to give us something more.”

I walk him outside. He’s parked in an illegal space around the corner from the hotel. I know I shouldn’t, but I can’t help myself, and I say, “Let me come with you. I may be able to help. You’re going to have to review missing persons reports. You’re going to have to figure out who that was who was buried up there, look for links to the other victims, to Erin. I can help with that. I know how to do it.”

My voice is whining. I’m ashamed and yet I want in on this so much, I don’t care what he thinks of me.

Roly rubs his eyes, watches a group of teenage boys cross the street in front of us. Finally he says, “D’arcy, I’m doing everything I can, but you are a civilian.” He puts a hand up when I start to protest. “Yes, when you’re here, you’re a civilian. And I know that if it was you at the top of the investigation, you would be saying the same thing as well. You have a role to play here. You knew her better than any of us did and you were here twenty-three years ago and I know you’re an amazing detective. I read the stories.” He fixes his gaze on me. His eyes are a pale ice blue in the direct sunlight. “I know what you did. But this is my show, and even more importantly, it’s Wilcox’s show, and if I let a civilian sit in on a briefing with the deputy state pathologist, Wilcox will have my head and we won’t be any closer to figuring out what happened to Erin or to saving Niamh Horrigan from whatever psychopathic piece of shite plucked her out of the mountains.”

Sirens scream outside, somewhere up near O’Connell Street.

“Okay,” I say. “I know. You’re right.”

Roly’s hair looks thinner somehow. I have that displaced feeling of déjà vu, except of course it actually is happening again. His words, his exhausted face and voice.

He reaches across me to open my door. “I’ll ring you as soon as I’ve got anything to report.” He pulls out so fast he almost clips me before I can jump onto the curb, and I’m still startled, stumbling back toward the Westin’s main lobby door, when a large man, his belly stretching his shirt beneath a voluminous tweed jacket, his eyes friendly behind round glasses, puts himself between me and the hotel. He has a straggly dirty-blond-and-gray ponytail. He was one of the reporters standing outside the pub in Glenmalure.

“Are you Detective Lieutenant Maggie D’arcy?” he asks. “Yes.” His face lights up in a smile and he sticks out a hand. I shake it, feeling vaguely manipulated.

“I’m Stephen Hines,” he says. “I’m a reporter for the Independent and I’m wondering if I could ask you a few questions.” He doesn’t wait for an answer, just plows ahead before my training kicks in and I can shut him down. “Is that your cousin they found in Glenmalure? Is that Erin Flaherty? Do you think she was a victim of the Southeast Killer? Are you going to help them find Niamh Horrigan?”

“I’m not going to comment on that,” I say, pushing past him.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members