AARP Hearing Center

Dr. Ethel Percy Andrus regarded the days of planning and preparation for the first White House Conference on Aging as the time when “aging came of age.” She could have said the same about AARP.

In 1958, the same year Dr. Andrus founded AARP, U.S. Representative John E. Fogarty of Rhode Island introduced legislation calling for a White House Conference on Aging. He said, “The concept of a White House Conference on Aging recognizes that a climate for ‘aging with a future’ is the concern of everyone in our land, and all levels of our society should accept responsibility for action.” Congress passed the bill and it was signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Dr. Andrus was determined to see the White House Conference succeed. The legislation had called for holding preliminary conferences in each state, and Dr. Andrus pulled out all the stops to see that these state conferences were well-attended. She didn’t stop there. She had AARP plan and conduct a nearly full-scale “dry run” of the national conference — what she called the “AARP Little White House Conference on Aging.” It was held in St. Petersburg, Florida, in January 1960. The keynote speakers were Congressman Fogarty and Dr. Bertha Adkins, President Dwight Eisenhower’s undersecretary of Health, Education, and Welfare.

President Eisenhower opened the first White House Conference on Aging in Washington, D.C., on January 9, 1961, and President-elect John F. Kennedy closed the conference on January 12. Supporting the conference theme, Aging with a Future — Every Citizen’s Concern, “Ike” told the more than 3,600 delegates, “In a world changing as rapidly as is ours, when we have gone from a pioneer civilization to a highly industrialized civilization in less than a century, we will do well to begin today to develop programs and policies that will make life better for the older people of the future.” JFK had campaigned for president in support of a program that “would tie medical care for the aged to the Social Security system,” the blueprint for Medicare. It was clear he strongly supported a new focus on aging.

A significant highlight of the 1961 Conference was what many have viewed as the birth of the “livable communities” movement. AARP and the Douglas Fir Plywood Association (now APA-The Engineered Wood Association) sponsored the design and construction of a compact “Retirement Demonstration Home” in downtown Washington at 17th and M streets, NW.

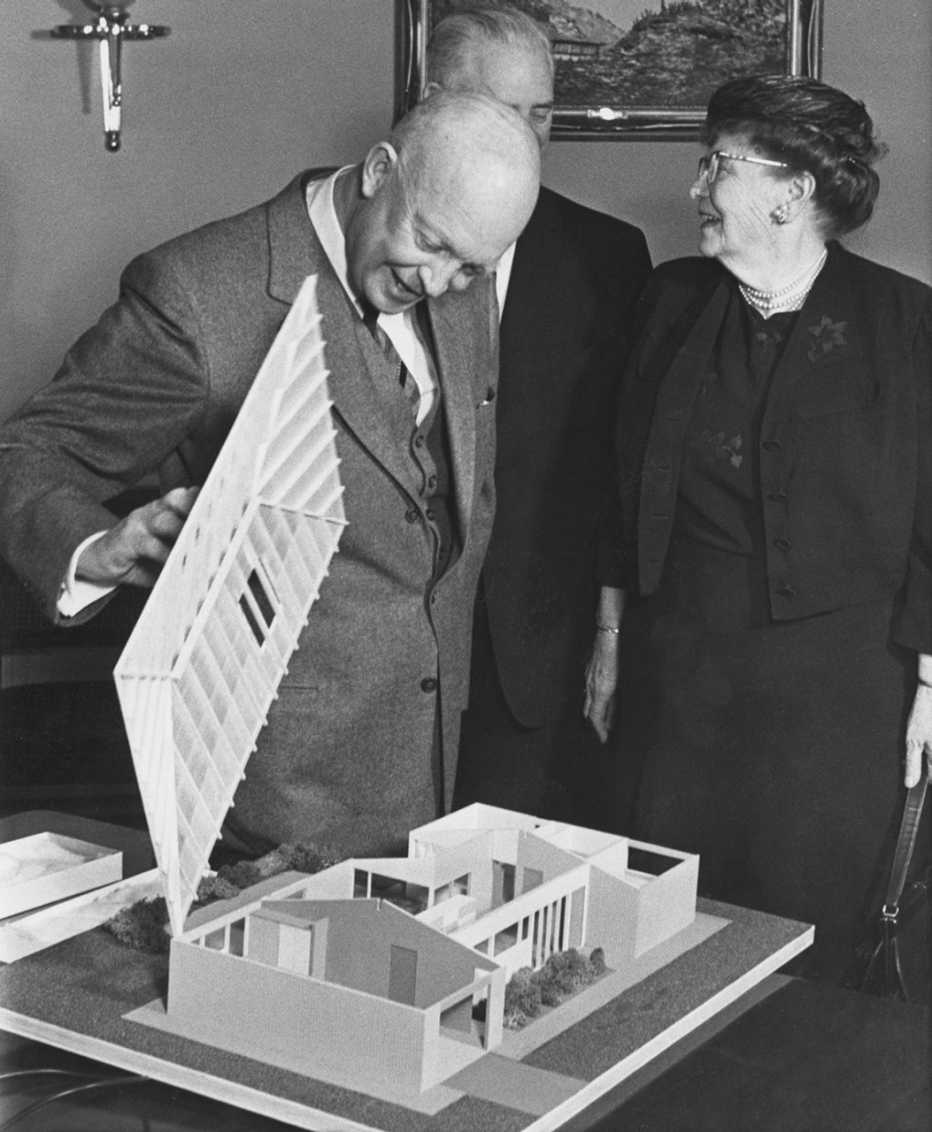

Known as the House of Freedom, it offered what came to be known as “universal design” features like no-step entries, 3-foot-wide doorways, lower cupboards and higher wall outlets to allow people of all ages to live safely and independently as they age. Dr. Andrus showed a scale model to President Eisenhower and presented him with the keys to the actual home; most of the White House Conference delegates paid a visit.

Dr. Andrus and AARP’s volunteer “army of useful citizens” played a major role in planning and promoting this historic conference. The problems identified by the conference delegates, along with the outlines for policy solutions offered, formed the basis for the action and debate on aging policy in this country that has continued to this day. William Fitch, AARP’s first executive director, said, “It was the first major awareness program in the broad field of aging. Many states had done little up to that point. Many set up committees on aging … and became sensitive to the fact that this was part of their future.” The conference was widely credited with leading directly to enactment of Medicare, Medicaid and the Older Americans Act, which established the U.S. Administration on Aging, among many other programs.