AARP Hearing Center

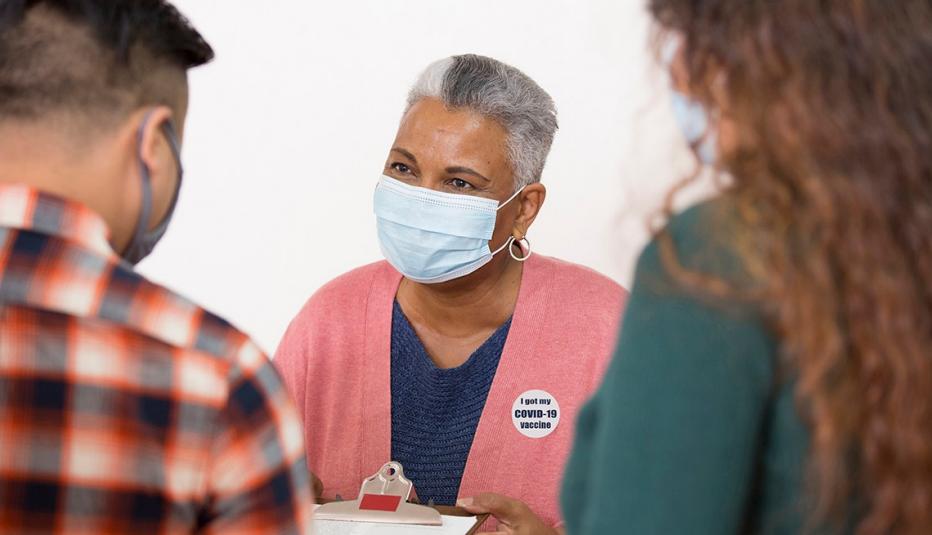

This report examines the current vaccine landscape and explores how key factors— including unfavorable attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination access and infrastructure—may limit the number of adults ages 50 and older receiving COVID-19 vaccines. It also discusses racial and ethnic disparities in vaccine attitudes and access and presents several policy and practice recommendations to help mitigate vaccination barriers and improve vaccination rates for older adults.

Attitudes

A 2020 AARP survey illuminated how vaccine attitudes can influence behavior, particularly older adults’ likelihood of getting a COVID-19 vaccine.

Among the 34 percent of respondents who reported being somewhat or very unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine, many raised safety and efficacy concerns about the vaccines. Over half (59 percent) of this group reported being concerned about a COVID-19 vaccine’s side effects. Nearly a third (29 percent) believed a vaccine would not protect them or does not work, and 16 percent perceived that they were healthy and did not need a vaccine. Wanting to keep away from health care sites and not being concerned about what will happen if they contract the virus were the least-cited reasons for planning to forgo a vaccine (13 and 12 percent, respectively).

Black and Hispanic older adults who indicated they were unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine were more worried about the vaccine’s side effects (63 and 69 percent, respectively) compared with their White counterparts (55 percent). Hispanic respondents had greater concern about the vaccine’s efficacy (38 percent) than White (28 percent) or Black (30 percent) older adults. Hispanics were also more likely to stay away from health care sites because of COVID-19 (27 percent) than their White (12 percent) and Black (11 percent) counterparts. Over two-thirds of Black respondents (67 percent) expressed a lack of trust in the government, a significantly higher share than among White or Hispanic respondents (both 42 percent).

The 2020 AARP survey also found that older Americans report only moderate levels of trust in local and national organizations to provide factual information about the COVID-19 vaccine. Providers are generally more trusted sources, with 74 percent of AARP survey respondents identifying their provider as the most trusted source of information around vaccines.

Vaccine Access and Infrastructure

Part of the vaccine decision-making process is where to get a vaccine. Traditionally, adults traveled to health care settings—primary care provider’s office, hospital, health department, or community-based clinic— to get vaccinated. However, as the vaccine infrastructure has shifted to make vaccines more accessible, some adults opt to use non-traditional settings, such as pharmacies, grocery stores, and their workplace. This has helped to increase flu vaccination rates.

Preferred locations for flu vaccinations differ by race and ethnicity. A health provider’s office is the preferred location for receiving flu shots among most racial and ethnic groups. White, Black and Asian adults are most likely to get their flu vaccination in this setting, while Hispanic adults are equally likely to go to another setting (e.g., hospital, community health clinic) as they are to go to a doctor’s office for their flu vaccines. White adults are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to get vaccinated at a pharmacy or supermarket.

The COVID-19 vaccination effort, both federal and in the states, does not mirror these existing patterns, which could have implications for uptake. A shift away from trusted settings and familiar processes for getting vaccinations has contributed to the widespread confusion about how to get a vaccine, questions about when and how one becomes eligible to get a vaccine, distrust toward groups involved in vaccine administration and, ultimately, delays in vaccination. Furthermore, online registrations can make it difficult for those without a computer, reliable internet, or computer literacy to get an appointment or find out where to go, exacerbating a digital divide that disadvantages older adults, rural residents, and people of color.

Significantly, a recent survey found that among people still deciding whether they want to get vaccinated, Hispanic and Black respondents had more concerns about transportation to a vaccination site, or having to take time off work to get vaccinated, than White respondents. The uneven distribution of an increasing but limited supply of COVID-19 vaccine doses may leave behind those who face greater access barriers.

Policy & Practice Recommendations

Despite recent survey data from AARP, Kaiser and other sources showing growing favorability toward COVID-19 vaccines, health officials and providers still face the dual challenges of effectively managing vaccine distribution and administration for older adults and combatting negative vaccine attitudes and vaccine hesitancy. The report concludes with detailed recommendations regarding both 1) vaccine attitudes, behavior, and hesitancy and 2) vaccine access and infrastructure.