AARP Hearing Center

When a finance worker in Hong Kong was called in to a live videoconference by the chief financial officer of his multinational company in February, everything seemed normal. The CFO and other executives acted and sounded as they always did, even if the reason for his being dragged in was unusual: He was instructed to wire $25.6 million to several bank accounts. He, of course, did as the boss asked.

Amazingly, the “CFO” image and voice were computer-generated, as were those of the other executives who appeared on the call. And the accounts belonged to scammers. The worker was the victim of a stunningly elaborate artificial intelligence scam, according to local media reports. The millions remain lost.

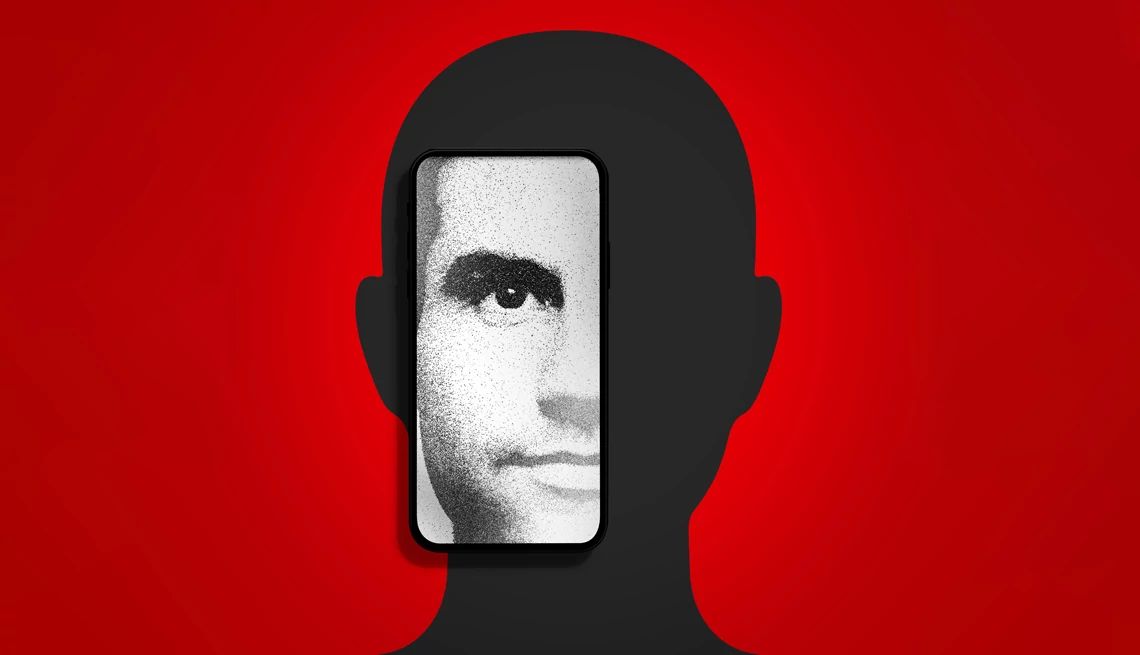

Welcome to the dark side of AI technology, in which the voices and faces of people you know can be impeccably faked as part of an effort to steal your money or identity.

Scientists have been programming computers to think and predict for decades, but only in recent years has the technology gotten to the level at which a computer can effectively mimic human voices, movement and writing style and — more challenging — predict what a person might say or do next. The public release in the past two years of tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and DALL-E, Google’s Gemini (formerly Bard), Microsoft’s Copilot and other readily available generative AI programs brought some of these capabilities to the masses.

Learn more

Senior Planet from AARP has free online classes to help you discover more about artificial intelligence.

AI tools can be legitimately useful for many reasons, but they also can be easily weaponized by criminals to create realistic yet bogus voices, websites, videos and other content to perpetrate fraud. Many fear the worst is yet to come.

We’re entering an “industrial revolution for fraud criminals,” says Kathy Stokes, AARP’s director of fraud prevention programs. AI “opens endless possibilities and, unfortunately, endless victims and losses.”

Criminals are already taking advantage of some of those “endless possibilities.”

Celebrity scams. A “deepfake” (that is, a computer-generated fake version of a person) video circulated showing chef Gordon Ramsay apparently endorsing HexClad cookware. He wasn’t. Later, a similar deepfake featured Taylor Swift touting Le Creuset. The likenesses of Oprah Winfrey, Kelly Clarkson and other celebs have been replicated via AI to sell weight loss supplements.

Fake romance. A Chicago man lost almost $60,000 in a cryptocurrency investment pitched to him by a romance scammer who communicated through what authorities believe was a deepfake video.

Sextortion. The FBI warns that criminals take photos and videos from children’s and adults’ social media feeds and create explicit deepfakes with their images to extort money or sexual favors.

Eyal Benishti, CEO and founder of the cybersecurity firm Ironscales, says AI can shortcut the process of running virtually any scam. “The superpower of generative AI is that you can actually give it a goal; for example, tell it, ‘Go find me 10 different phishing email ideas on how I can lure person X.’ ”

Anyone can use this technology: “It’s just like downloading any other app,” says Alex Hamerstone, an analyst at TrustedSec, an information security consulting company. “If you were recording this conversation, you could feed it into the software and type out whatever you want me to say, and it would play my voice saying that.”

More From AARP

White House Announces Sweeping New Efforts to Protect Americans From AI’s Dangers

Measures are meant to prevent fraud, keep infrastructure secure and protect privacy as new tech brings risks

FCC Outlaws Robocalls Made With Artificial Intelligence

Agency says AI makes rampant scam calls that could deceive voters

AI, Voice Cloning and Scams: What You Should Know

Artificial intelligence is being used to supercharge the common grandparent and impostor scams

Recommended for You