AARP Hearing Center

1. A Definition: A good zoning code clearly defines its terminology. Here, for example, is a useful outline for what, in the real world, is a very fluid term: “An ADU is a smaller, secondary home on the same lot as a primary dwelling. ADUs are independently habitable and provide the basic requirements of shelter, heat, cooking and sanitation.”

2. The Purpose: This is where the code describes key reasons a community allows ADUs. They should:

- increase the number of housing units while respecting the style and scale of single-dwelling development

- bolster the efficient use of existing housing stock and infrastructure

- provide housing that’s affordable and respond to the needs of smaller, changing households

- serve as accessible housing for older adults and people with disabilities

3. Eligibility: Who can build an ADU and on what type of property? A statement in this part of the code clarifies that an ADU can be placed only on a “residentially zoned, single-family lot.” (Some communities provide lot size standards, but many don’t.)

4. Creation: This is where the code sets out how an ADU can be built. For instance: “An ADU may be created through new construction, the conversion of an existing structure, as an addition to an existing structure or as a conversion of a qualifying existing house during the construction of a new primary dwelling on the site.”

5. Quantity: Most municipalities that permit ADUs allow one per lot. Vancouver, British Columbia; Sonoma County, California; and Tigard, Oregon, are among the few that allow two per lot (typically one internal and one external). Some communities also allow duplexes or townhomes to have ADUs, either in the backyard or on the ground floor.

6. Occupancy and Use: A code should state that the use-and-safety standards for ADUs match those that apply to the primary dwelling on the same property. (See page 17 for more about ADU uses.)

7. Design Standards:

- Size and height: A zoning code might specify exactly how large and tall an ADU is allowed to be. For instance, “an ADU may not exceed 1,000 square feet or the size of the primary dwelling, whichever is smaller.” Codes often limit detached ADUs to 1.5 or 2 stories in height. (An example of that language: “The maximum height allowed for a detached ADU is the lesser of 25 feet at the peak of the roof or the height of the primary dwelling.”)

- Parking: Most zoning codes address the amount and placement of parking. Some don’t require additional parking for ADUs, some do, and others find a middle ground — e.g., allowing tandem parking in the driveway and/or on-street parking.

- Appearance: Standards can specify how an ADU’s roof shape, siding type and other features need to match the primary dwelling or neighborhood norms. Some codes exempt one-story and internal ADUs from such requirements.

- Entrances and stairs: Communities that want ADUs to blend into the background often require that an ADU’s entrance not face the street or appear on the same facade as the entrance to the primary dwelling (unless the home already had additional entrances before the ADU was created).

8. Additional Design Standards for Detached ADUs:

- Building setbacks: Many communities require detached ADUs to either be located behind the primary dwelling or far enough from the street to be discreet. (A code might exempt preexisting detached structures that don’t meet that standard.) Although this sort of rule can work well for neighborhoods of large properties with large rear yards, communities with smaller lot sizes may need to employ a more flexible setback-and-placement standard.

- Building coverage: A code will likely state that the building coverage of a detached ADU may not be larger than a certain percentage of the lot that is covered by the primary dwelling.

- Yard setbacks: Most communities have rules about minimum distances to property lines and between buildings on the same lot. ADUs are typically required to follow the same rules.

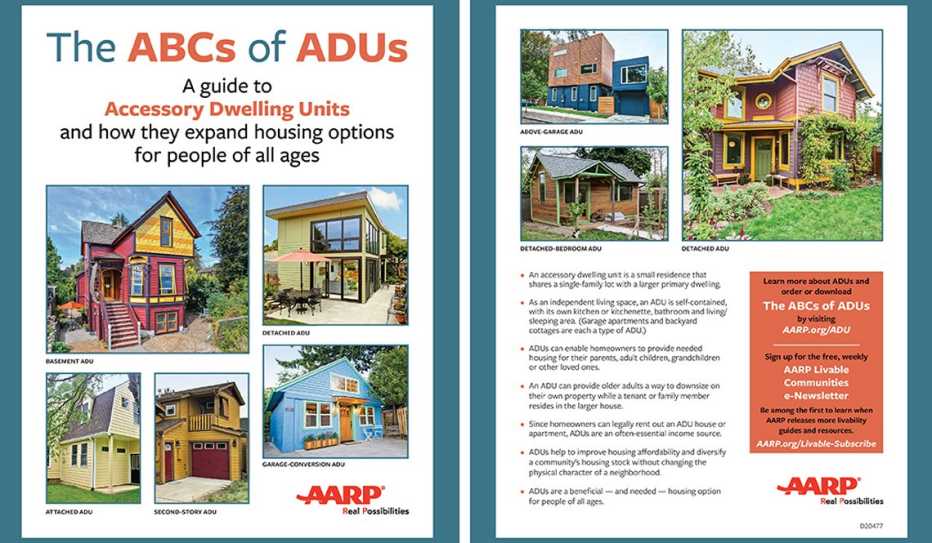

This article is adapted from The ABCs of ADUs, a publication by AARP Livable Communities. Learn more below. Learn more about ADU zoning codes and policies by downloading or ordering Accessory Dwelling Units: A Step-by-Step Guide to Design and Development, published by the AARP Public Policy Institute.

MORE ABOUT ACCESSORY DWELLING UNITS

Visit AARP.org/ADU for links to more articles and to order AARP's free publications about accessory dwelling units.