AARP Hearing Center

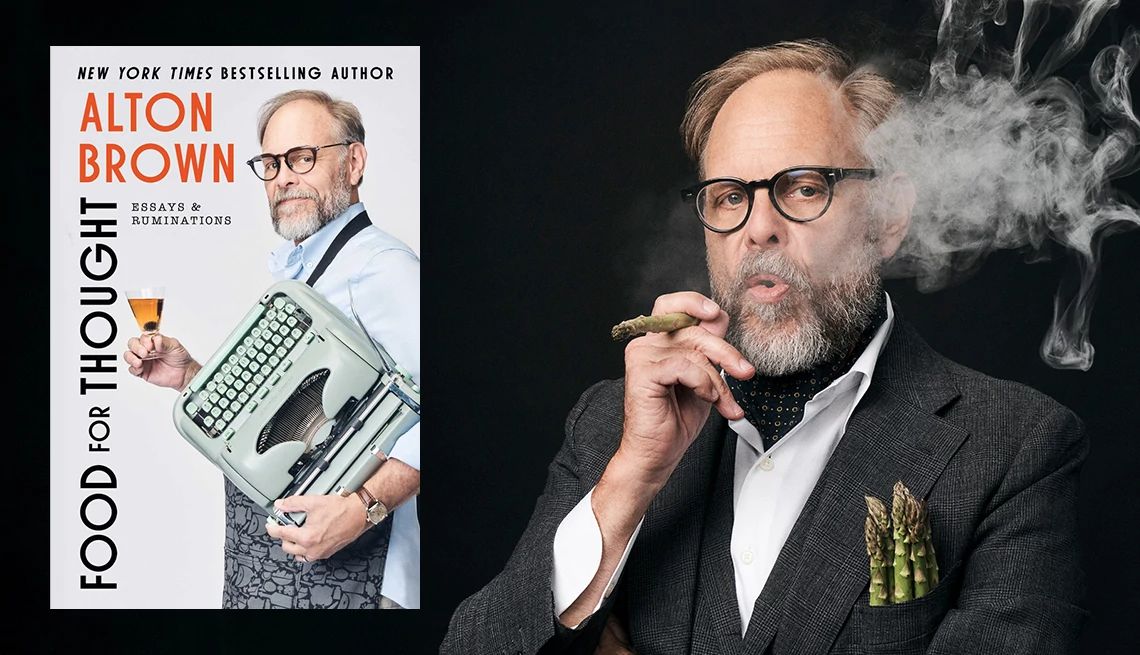

Alton Brown, 62, known for hosting Food Network shows like the long-running Good Eats, has written his first memoir, Food for Thought: Essays and Ruminations (February 4). It’s full of tales from his childhood and beyond, including one about his grandma Ma Mae’s homey biscuits and his efforts to recreate the warm, buttery goodness she perfected.

“Her biscuits probably weren't special to anyone but me and my grandfather,” he told AARP, “but there was something about the way that she cooked… she did it very genuinely.”

You can read Brown’s essay on Ma Mae’s unforgettable biscuits below — and find his favorite biscuit recipe here.

Biscuiteering

My maternal grandmother, Ma Mae, whom I adored, grew up humble in the mountains of North Georgia. She was a worker bee, and as a young woman, toiled in a fabric mill, raised two girls, gardened and canned her way through World War II, and fed her husband every day. Eventually she and my grandfather graduated to the merchant class; he owned a gas station and repair shop, and she ended up owning the most elegant women’s fashion store in the region.

This is all to say that she was a busy lady, and so her cooking style was what she called “plain ol’ home cookin’,” which meant not fussing with, fixating on or overthinking culinary matters, even when producing a glazed orange pound cake for a church luncheon, fried chicken for a family dinner, or anything else for that matter. Cooking was just a thing that needed doing, and back then it was a woman’s job to do because, according to my grandmother, when men attempt anything other than grilling steaks, they “make a mess of things.”

One thing I remember from my time spent with her as a kid is that no matter what was going on in life, Ma Mae got up early every day and cooked breakfast for her husband and anyone lucky enough to be visiting, including eggs, bacon or sausage, grits and fresh biscuits, which is to say: buttermilk biscuits, light, fluffy, about two inches across, well-browned, tangy. Although I’d witnessed folks dressing them with honey or jam, or building sausage sandwiches with them, sometimes with a kiss of mustard, I never craved anything but a pat of butter. To properly apply, the biscuit was first split with the tines of a fork, creating crags and crannies that the butter could nestle into as it liquefied. (A sharp knife cut would result in smooth surfaces, allowing the butter to run off it and onto the plate, a strictly amateur move.) Once buttered, the “lid” was replaced and the waiting began, approximately 90 seconds being required for the average pat of refrigerator-temperature butter to thoroughly seep into the bread.

You Might Also Like

TV Food Star Alton Brown, 62: ‘There’s No Such Thing As a Natural Bad Cook’

The dynamic science-nerd chef chats about his new book ‘Food for Thought,’ what makes a good cook and eating weird things as a kid

Alton Brown’s ‘Buttermilk Biscuits: Reloaded’ Recipe

Light and flaky biscuits like my grandma used to make — but better

18 Ways You’re Using Your Microwave All Wrong

Maximize efficiency, safety and taste