AARP Hearing Center

In this story

Wide-ranging features • Smart rings, too • 4 health features • Heeding the results • Cellular connections

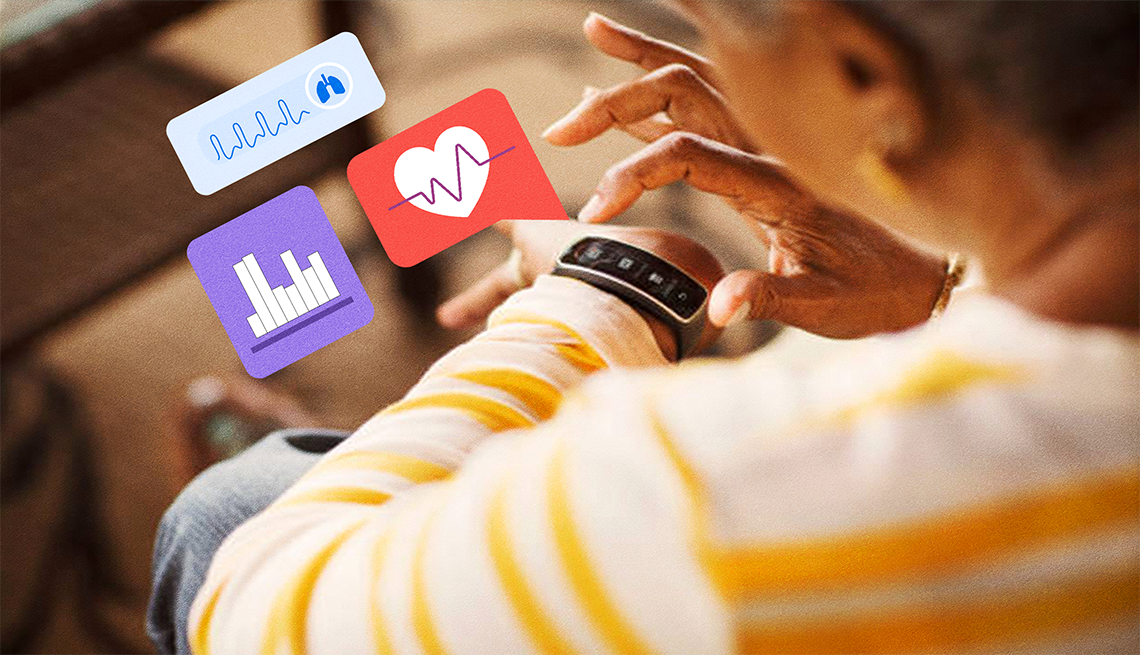

As you get older, you may be more eager than ever to track your fitness activity and get a better handle on what’s happening inside your body.

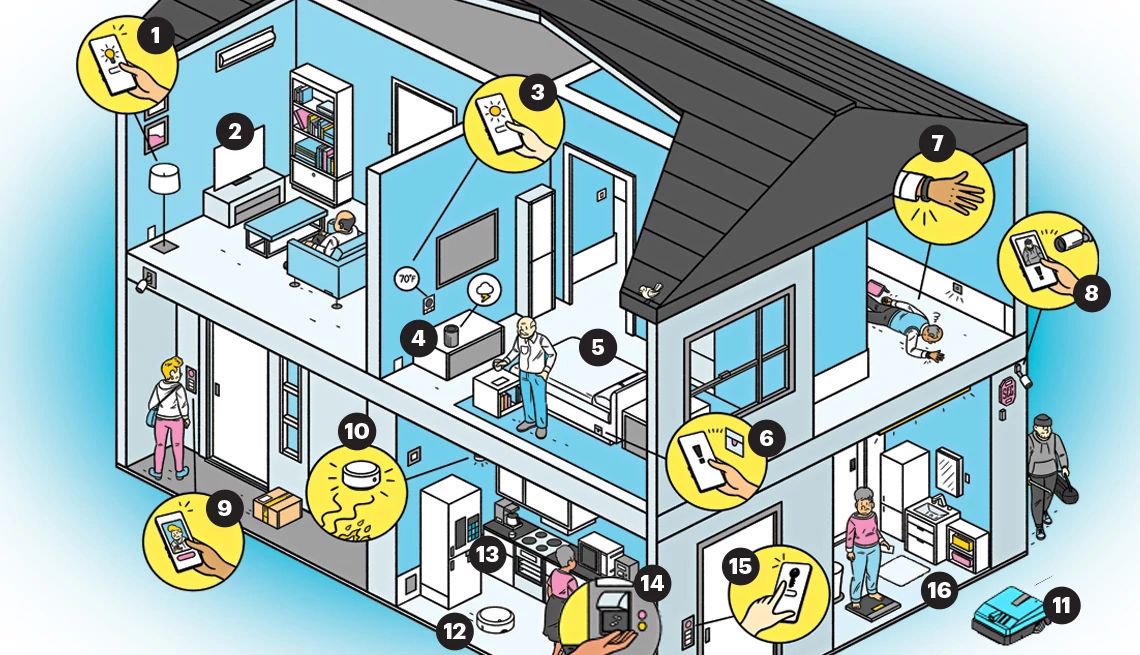

Insights into your health may come straight from your wrist. Apple’s latest Series 9 smartwatch, which starts at $399, coupled with the watchOS 10 software upgrade that some older models can take advantage of, can help you measure your cardio fitness while also detecting irregular heartbeats, excessive exposure to loud noises and how much sleep you’re getting. Apple also allows family members to see health information if given permission — handy for caregivers and recipients who want an extra set of eyes on an aging adult.

The watches can even remind you to wash your hands periodically. A 20-second countdown timer may automatically kick in to ensure you’re washing long enough. And recent Apple Watches can summon emergency medical assistance should you fall and become immobilized.

Rival wearables from Fitbit (now owned by Google), Samsung and other companies also are providing digital biomarkers that provide visibility into your health — well beyond the steps counted and calories burned that have long defined such devices.

Smart rings also track

If you want less weight on your hand but still want an unobtrusive way to monitor your health and sleep patterns, a smart ring could be the answer.

The first one debuted in 2013 and could unlock doors, start your car and make electronic payments with a tap.

Because they don’t have a screen, you must view data from the ring’s various sensors on an app, but you can wait as long as a week between charges.

Google also sells a smartwatch these days under its own brand name. The Pixel Watch 2, starting at $299.99, bakes in some Fitbit features and runs off the latest version of Google’s Wear OS software platform, the flavor of Android designed for wearables. Google’s original Pixel Watch, still in the lineup, starts at $179.99.

Wear OS 5 is expected to be previewed at Google’s annual I/O developer conference this week at its Mountain View, California, headquarters. It remains to be seen if Google teases a new Pixel Watch or Fitbit hardware during the event.

“This is a new era where we have an opportunity to reach the patients outside the walls of the hospital,” says Nino Isakadze, M.D., a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore who studied atrial fibrillation (A-fib) and wristband technology during her residency. “Patients can be empowered by having this type of data and be able to track their progress and be more aware of their health overall.”

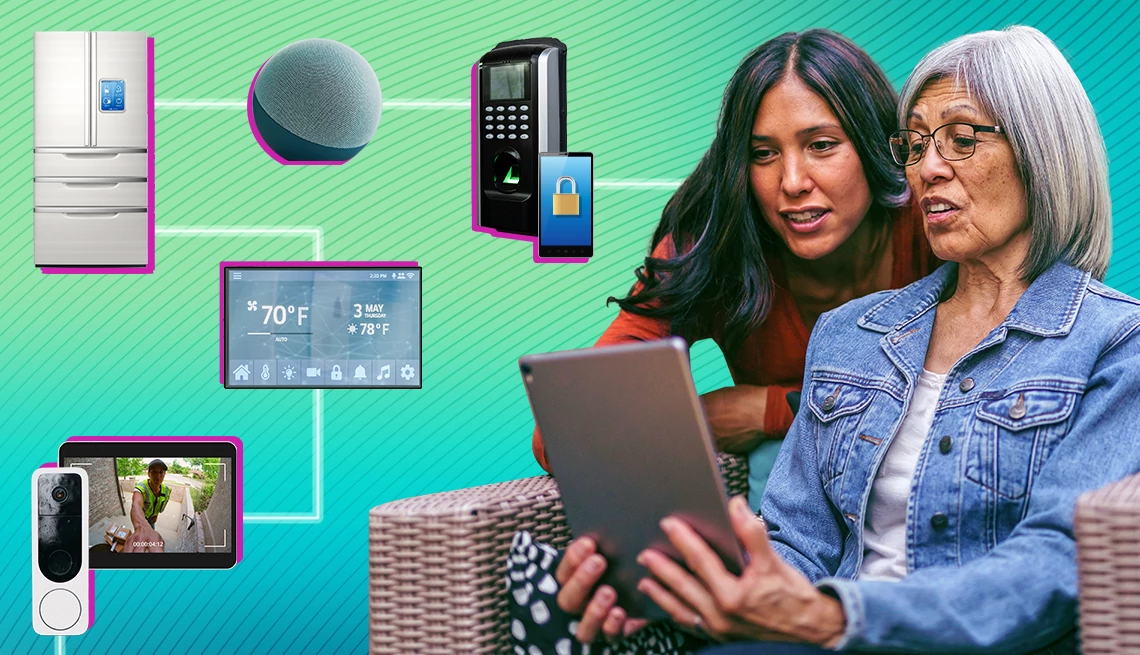

Smartwatches share data with companion health apps on your iPhone or Android devices. For those enrolled in Medicare Advantage or other insurance plans, note that some smartwatches are available at a discount as a member benefit.

Around 1 in 5 adults 50 and older who go online use a smartwatch, according to Cambridge, Massachusetts market researchers Forrester.

4 health features to watch out for

1. Electrocardiogram. In 2018, Apple took a major step in putting power in the hands of consumers when it added an electrocardiogram app to its Series 4 Apple Watch models, which has carried over to subsequent models. The app, which is called ECG rather than the more commonly known EKG abbreviation, can detect A-fib, an irregular heartbeat that is a major risk factor for blood clots and stroke.

It has clearance from the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA). On May 1, the FDA announced that the “history” feature of Apple’s A-fib technology was the first to qualify under the agency’s Medical Device Development Tools (MDDT) program, meaning it can be used in clinical studies to check estimates of how often a patient was in A-fib and the effectiveness of treatments.

Google’s Fitbit also received regulatory clearance from the FDA for its own EKG app, now on the Fitbit Sense 2 health-oriented watch, starting at $199.95 and Charge 6 devices, as well as the Pixel Watch models.

Samsung has its own FDA-cleared heart-monitoring ECG app on the Galaxy Watch6 which starts at $299.99. Older models, such as the Galaxy Watch4 and Galaxy Watch5, which you might still find at reduced prices, also have the feature.

More From AARP

5 Ways Tech Can Help Caregivers of Dementia Patients

Wearables, smart homes, other solutions don’t work for all

Find Out How Your Smartphone Can Help Save Your Life

Let first responders see medical information, emergency contacts without knowing your code

AARP's Fast-Action Guide to Replacing Appliances

When your home essentials break and there's no time to lose, these shopping tips can help

Recommended for You