AARP Hearing Center

As social media platforms — including Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and X — move away from independent fact checkers and embrace crowdsourcing for pointing out problems in posts, older adults will increasingly have to rely on their own methods for determining fact from fiction.

Figuring out what’s real and what’s not will get even harder in cyberspace, especially because artificial intelligence (AI) and visual effects are increasingly being used to make fake photos and videos look authentic and even create entire websites.

Meta announced Jan. 7 that it is phasing out its independent fact-checking program in the U.S., begun in 2016, and moving to what it calls Community Notes, where anonymous users will contribute and rate content in a similar fashion to what is done on X, formerly known as Twitter. Meta’s Facebook and Instagram apps are among the most popular with adults 50 and older, according to AARP Research.

“Meta’s platforms are built to be places where people can express themselves freely. That can be messy,” Joel Kaplan, Meta’s new chief global affairs officer, wrote on the company’s website. On platforms where billions of people can have a voice, all the good, bad and ugly is on display. But that’s free expression.”

Social media evolves into source for news

Facebook was a recent source of news for nearly 2 in 5 U.S. adult citizens, according to an April 2023 poll from YouGov, a London-based market research firm. More than half of the poll’s respondents were 45 and older.

Two-thirds of those 65 and older who were polled said they were seeing false information online daily. Three in 5 of those 45 to 64 said they were seeing the misleading info on the internet every day.

“It’s laughably dystopian: Meta flooding its platforms with AI bots and removing human fact-checkers. Not going to be a good year for truth,” Alex Mahadevan, director of the MediaWise digital literacy initiative at Poynter Institute for Media Studies in St. Petersburg, Florida, wrote on X and Threads competitor Bluesky.

In a 2022 interview with AARP, Mahadevan cited political polarization and advances in technology as chief factors behind the increase in misinformation. Amplification of falsehoods through social media has exacerbated the problem.

Do you know how to verify what you see?

Worldwide, nearly 3 in 5 respondents to another survey also say they worry about identifying the difference between real news and fake on the internet, according to a 2024 report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University. In the U.S., 72 percent of those polled were worried.

“We’re all vulnerable to misinformation,” says Hannah Covington, senior director of education content at the nonpartisan News Literacy Project in Washington, D.C. The program provides free resources, including quizzes, to teach people how to identify credible news.

“We know that young people struggle to identify misinformation. We know that older folks have also struggled to identify misinformation,” she says. “Misinformation targets people on the political right, on the left. It comes from foreign sources, domestic sources.”

MediaWise also offers free online courses to help people spot misinformation. AARP is a sponsor, along with Facebook, of a MediaWise for Seniors initiative that includes free self-guided online courses with journalists Christiane Amanpour of CNN and Joan Lunden.

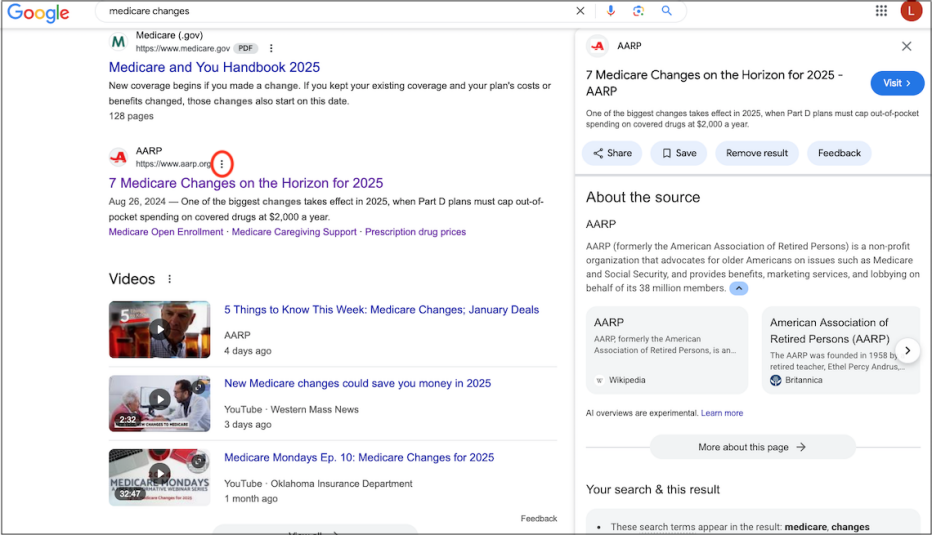

Here are recommendations from experts that may help you recognize falsehoods online.

More From AARP

Can I Stop Facebook, X From Using Me to Train Their AI?

You didn’t opt in, but you may have options for privacyGoogle Is Deleting Inactive Accounts

Here's how you can save yours5 Tips to Determine if What You See on Twitter is Real

New blue check marks will require you to be a sleuth