AARP Hearing Center

Older adults make up almost a quarter of all ER visits, according to a 2024 report published in the International Journal of Emergency Medicine. And nearly 80 percent of them claim they leave the ER with at least one health concern that they feel wasn’t addressed.

That’s just the beginning of what can be a frustrating ordeal. A 2025 JAMA Internal Medicine research letter analyzing more than 12 million visits across 1,600 hospitals found that 20 percent of older patients had ER stays exceeding eight hours — up from 12 percent in 2017.

When it comes to the ER, even the most seasoned patients can feel overwhelmed. That’s where Dr. Adaira Landry can help. She’s an emergency medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, with years of experience treating patients in high-pressure, high-stakes situations. Landry shares insider tips, in her own words, to help you stay calm, ask the right questions and get the best possible care when every minute counts.

1. Know your ERs before you need one

Not all emergency departments are equal — some are stroke centers, some have cardiac catheterization for heart attacks, and some are academic hospitals where you’ll see trainees like medical students and residents. When you see your primary care doctor, ask about nearby hospitals. And if your PCP ever recommends you go to the ER, discuss which ER is best for the complaint you are having.

That said, I wouldn’t stress too much about having the “perfect” plan, because this info isn’t always easy to find and memorize. In a true emergency, the best hospital is often the closest hospital.

2. There is no “perfect” time to go to the ER

The best thing you can do is come in when symptoms first start to concern you or your loved ones. If you come in early for a urinary tract infection, for instance, you might leave with oral antibiotics. If you wait too long, you may become sicker and need IV antibiotics with an overnight stay.

3. Hope for fast, prepare for slow

It used to be that very early mornings (between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m.) were quieter, but that was before the pandemic, and these days ERs can feel busy all the time.

Hospital websites and apps like EmergConnect, Vital Emergency and Emergency Q can tell you how long the wait will be, but these should be taken with a grain of salt. ER wait times are difficult to predict, even for us inside the hospital. Instead of trying to avoid a wait, it’s better to prepare for it. Assume you could be in the waiting room for three to four hours (sometimes longer), and then another few hours in the ER while a plan is made.

I tell people to bring a phone charger, have someone lined up to watch the pets or kids, and expect to cancel meetings or plans for the day. It’s best to prepare for a longer visit.

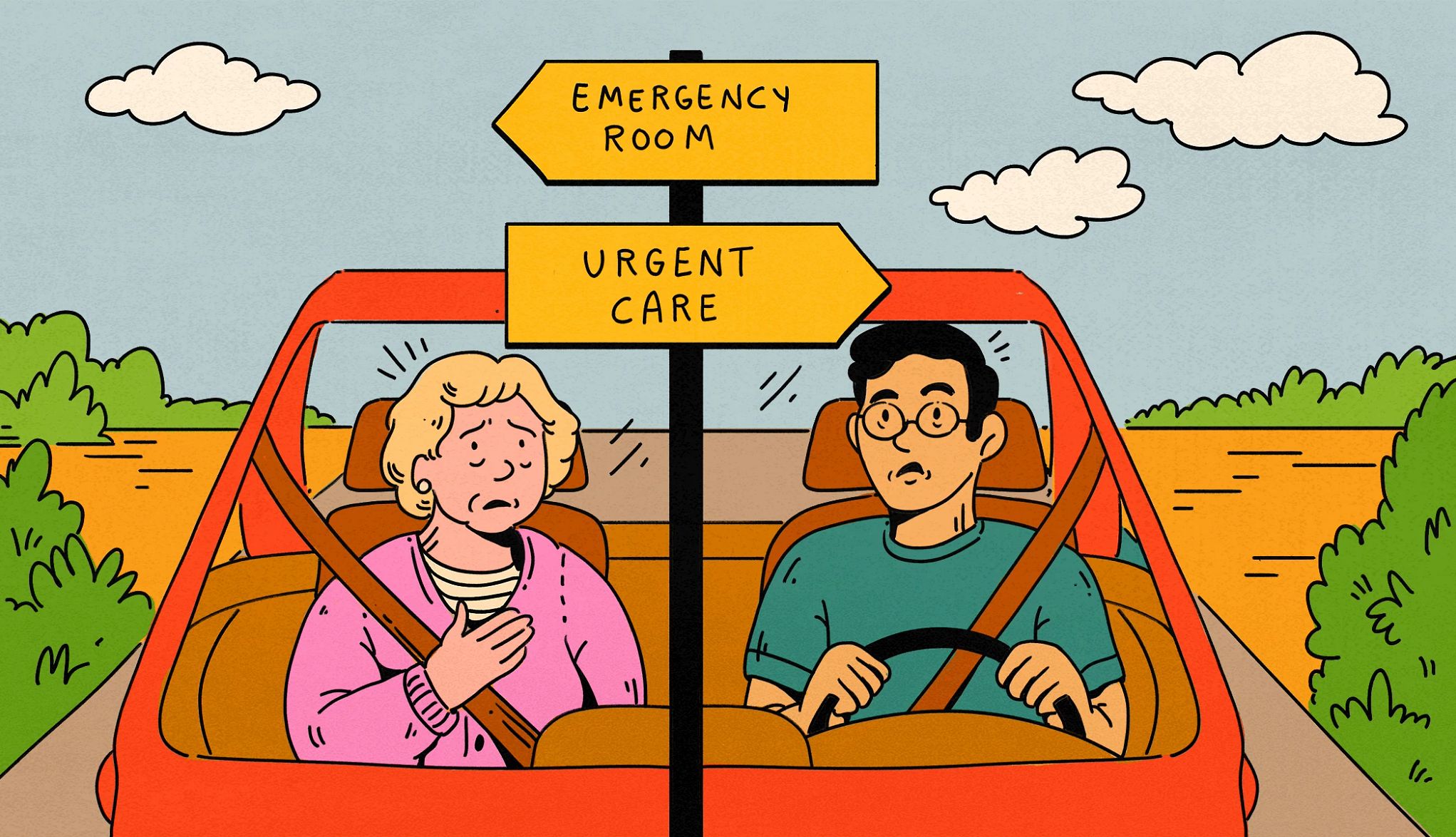

4. Twisted ankle? That’s urgent care. Chest pain? ER, please

Urgent care visits are usually best for less complex, more straightforward issues. A good example: You twist your ankle, and now it’s swollen and a little painful when you walk. That’s perfect for urgent care.

Going to the ER could be a better choice if your medical history makes complications more likely, you need advanced diagnostics like a CAT scan or MRI (some urgent cares don’t have these tools), you might need multiple specialists involved, or even an overnight stay. For example, you twisted your ankle, lost consciousness and fell, hit your head or landed on your chest, and now have shortness of breath. And maybe your ankle looks badly deformed. Maybe you are on medication that thins your blood, making a brain bleed more likely. That’s an ER case. It’s a much more involved situation.

You Might Also Like

AARP Smart Guide to Surgery

Tips to help you prepare for and recover from an operation

Top Colorectal Surgeon Shares Insider Secrets

Don't let embarrassment keep you from getting answers

Is a Full-Body Scan Worth the Money?

A doctor’s advice on what to consider when weighing the cost of head-to-toe imaging