AARP Hearing Center

Key takeaways:

- Cochlear implants can help with moderate to profound hearing loss.

- A cochlear implant evaluation includes hearing tests and a health check.

- Cochlear implant surgery is usually an outpatient procedure.

- Rehab after cochlear implant surgery helps you learn how to hear with the devices.

- Therea re both pros and cons to having cochlear implants.

Joyce Purnick says that when her cochlear implant was turned on in 2019, she had a typical experience: She heard sounds, but they were “completely unintelligible … weird whistles and screeches.”

Then, three weeks later, just as her surgeon and audiologist had promised, the noises suddenly became speech – specifically, the voice of Lester Holt delivering the evening news.

“It really was awesome,” says the 79-year-old retired journalist, who lives in New York City.

Purnick, who started losing her hearing just before turning 60, says her implant-assisted hearing isn’t perfect, but it is much better than it was with hearing aids alone. “It’s been a very positive experience,” she says.

What is a cochlear implant?

Cochlear implants are electronic devices that can help people hear when hearing aids are no longer enough. Despite experiences like Purnick’s, many older adults aren’t getting these implants, experts say.

“There’s limited awareness” of the option, says Matthew Carlson, an ear surgeon and professor of neurosurgery and otolaryngology at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. Just 2 to 12 percent of adults who could benefit get them, he says.

Many people incorrectly think cochlear implants are only for children or are “the absolute last resort,” says Marquitta Merkison, associate director of audiology practices at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Still, cochlear implants aren’t for everyone, and they do require surgery and follow-up training.

Here’s what to know.

Cochlear implants vs. hearing aids

Hearing aids, devices worn outside or in the ear, work by making sounds louder. They don’t change how your ears or brain handle sounds. Cochlear implants change your hearing in a more fundamental way.

The key difference, Carlson says, is that a cochlear implant bypasses your inner ear nerve endings, called hair cells, that are damaged or missing in people with hearing loss related to aging, noise exposure, genetics or other factors. Instead, it sends sound information, in the form of electrical impulses, straight to one key nerve, called the cochlear nerve, and on to the brain.

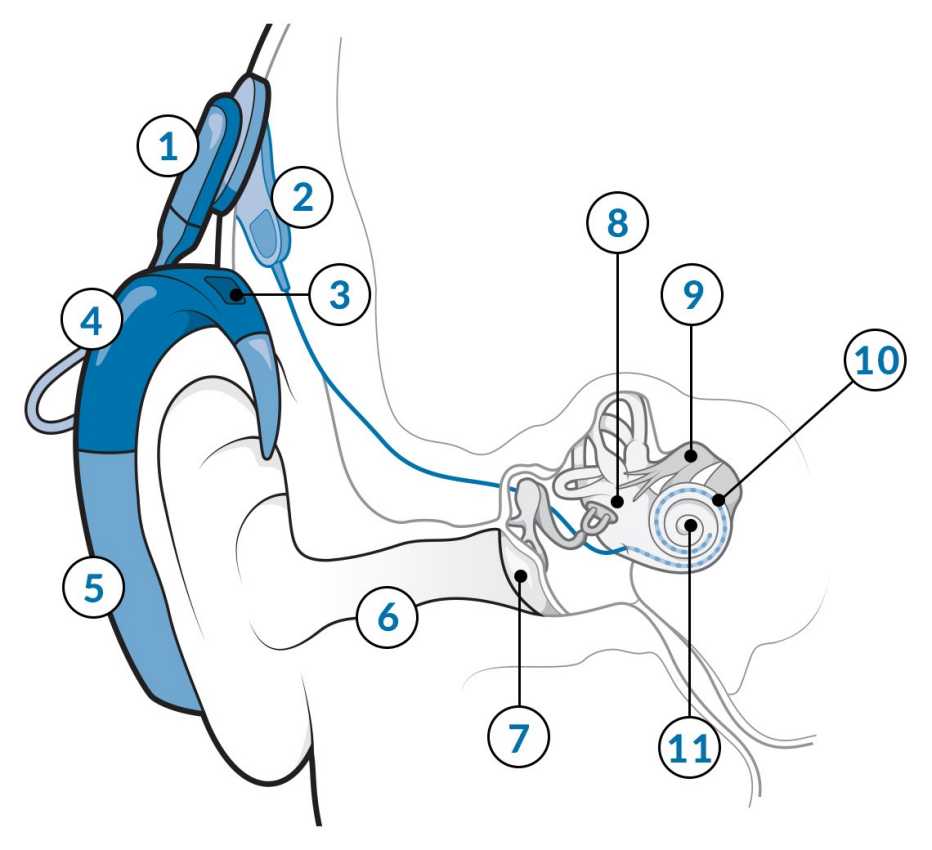

Cochlear implants have a transmitter and other parts that you wear outside your ear, and key parts are placed inside your ear. The outer electronics, which include a microphone and sound processor, can look like many hearing aids, Merkison says. A unit that looks “like an upside-down J,” she says, may go behind your ear (or clip to your clothes, if preferred) and have a cord leading to a transmitter. The microphone, sound processor and transmitter may be combined in one unit.

How cochlear implants work

Cochlear Implants: How They Work

The processor and microphone sit behind the ear and send sound to electrodes implanted in the cochlea. Those electrodes bypass the cilia and convey signals directly to the auditory nerve, which relays the message to the brain.

The receiver is implanted behind your ear, under the skin, to get signals from the transmitter. It’s connected to electrodes placed inside the cochlea, the part of your inner ear that contains hair cells.

The electrodes send signals to the cochlear nerve, which sends them to the brain, which — with time and practice — can turn them into recognizable speech and other sounds.

People typically get one implant at first; sometimes they get a second one later.

Three companies make cochlear implants approved for use in the United States. Models can vary a bit, so patients should discuss options with their care team, Merkison says.

A suggestion from Purnick: Ask your surgeon which implants they use most.

Who can get a cochlear implant?

“A common misconception is that you need to be totally deaf to get one,” Carlson says. In fact, people with moderate to profound hearing loss may qualify if they have working cochlear nerves.

A cochlear implant evaluation makes sense if you’ve tried good, properly adjusted hearing aids and still “can’t understand people, especially when there’s background noise,” Carlson says.

Next in series

Listen to Your Hearing and Learn How to Treat It

Hear about the hearing health issues that affect you as you age, from earwax to tinnitus