AARP Hearing Center

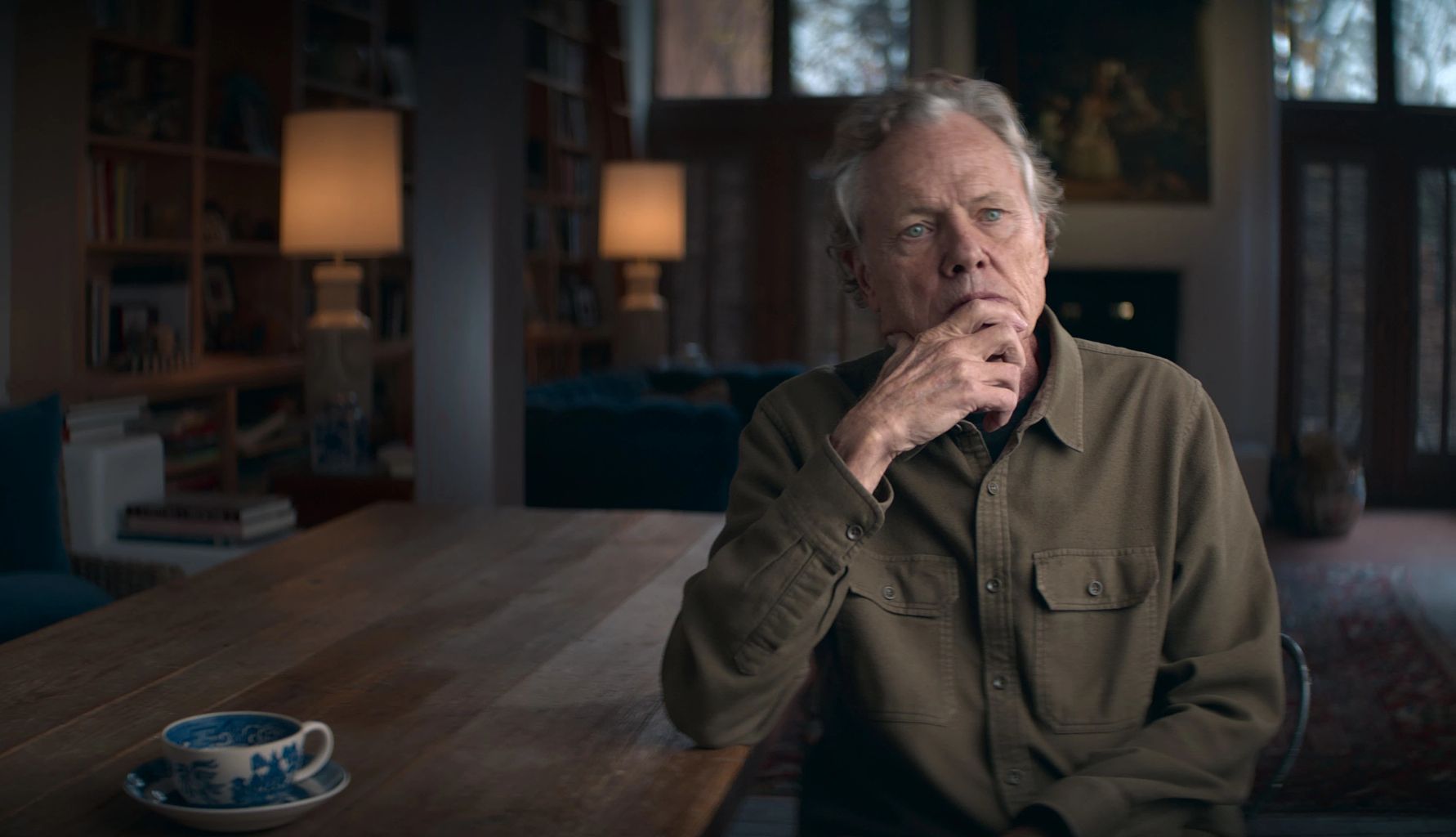

Apollo 13 screenwriter William Broyles, Jr., 80, is the only Oscar nominee who went from Oxford University to Vietnam to Hollywood, where he created the Vietnam-set series China Beach and wrote Cast Away, Planet of the Apes, The Polar Express, Jarhead and the AARP Movies for Grownups Award-winning World War II movie Flags of Our Fathers.

He worked at Newsweek, founded Texas Monthly, wrote the classic memoir Brothers in Arms: A Journey from War to Peace about his return to Vietnam 15 years after the war, and appears in the riveting new documentary Vietnam: The War That Changed America (Jan. 31, Apple TV+), narrated by Ethan Hawke, 54. Broyles tells AARP about the war and the new documentary.

Why should people watch Vietnam: The War That Changed America?

This is a must-watch for all Americans, but particularly AARP people, because this is our generation. I’m in AARP, and there are many Vietnam vets in the organization. It’s a beautiful film, and most people of our generation were touched by the war.

Where were you when you saw the TV news of the 1968 Tet Offensive, the North Vietnamese surprise attack that penetrated the U.S. embassy, hastening the war's end?

I was in Oxford having high tea. You could hear the bullets flying, and a Marine told the cameraman, “I don’t know what this is all about, I just want to get out of here and go back to school.” I realized if I kept my draft deferments, someone else — like him, like the kids I grew up with in Baytown, Texas — would have to go in my place. They found that guy, he’s in the miniseries.

What was it like when you helicoptered onto a hilltop in Vietnam?

People say we had ten years’ experience in Vietnam. We didn't. We had one year's experience ten times, because the minute someone got to know what was really going on, they rotated home, and someone else came in their place. I was this newly minted green Second Lieutenant sent to this unit, which had not had an officer for some time.

More From AARP

Drew Barrymore Joins the 50-Plus Club

Celebrating the joy of turning 50 and embracing new milestonesTV Preview 2025: The 20 Shows We Can't Wait to See

See Robert De Niro's 'Zero Day,' Noah Wyle's ER drama 'The Pitt' and more

The Oscar Winner Who Almost Became a Life Coach

Actor-musician Common reveals his backup plan if Hollywood didn't work out