Q: Character.

That's right. I think about Lincoln on that train ride to Gettysburg, penning his address and listening to that a--hole before him speak for over an hour and a half, who was just drubbing him. And then Lincoln sitting there, looking at his puny 270 words or whatever they were and thinking, Oh man, I've miscalculated here. And it stands forever. Forever. And that blowhard is not even a moment. He is only connected because Lincoln was so great.

Q: What drew you to make Let Him Go, a dark western gothic set in 1951? You play a grieving father who finds himself headed for trouble.

It felt honest. Men sometimes have to follow their women. [My character] George knows his wife is right, but he knows exactly where this leads. The western is not based on one person's story. It's based on something that probably happened thousands of times. The first western I did, Silverado, wasn't history, it was good matinee fun. Later on I did Wyatt Earp, which was more biographical. My western Open Range was based on a novel, yet the conflict it showed between free grazers and the people who were fencing in land with barbed wire could have played out a thousand times. I don't think because something is fiction doesn't mean you can't find yourself.

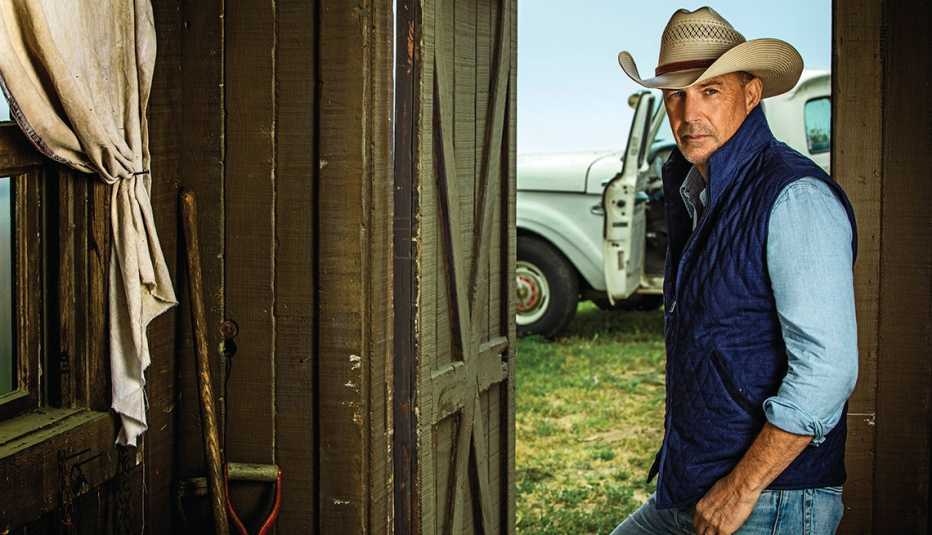

Kevin Costner Reflects on His Western Roles

Western Star

Costner's career on the range

Silverado (1985)

A 30-year-old Costner plays Jake, a misfit cowboy, who joins his brother on a journey to a troubled town.

Dances with Wolves (1990)

Costner stars as a Civil War lieutenant who develops a bond with a tribe of Lakota. He also directed the film and won the Academy Award for best director.

Wyatt Earp (1994)

In the title role, Costner portrays the legendary lawman torn between his live-by-the-code career and loyalty to his family.

Open Range (2003)

Playing a cowhand, Costner helps drive a herd of cattle across Montana. When one of his fellow cowboys is attacked, vengeance ensues, resulting in a long shootout finale.

Yellowstone (2018–present)

As the patriarch of a powerful ranching family, Costner must defend his land against developers, an Indian reservation and the first U.S. national park in this neo-Western TV series.

Let Him Go (2020)

Costner stars as the retired sheriff who, with his wife (Diane Lane), leaves his Montana ranch to rescue his young grandson from a nefarious family. Coming this fall. —Emily Paulin

Q: Your new film explores what it means to protect those you love, the sacrifices parents make. Did you have a good relationship with your folks?

My dad was pretty tough. My mom was the one that let me know things were possible. I was a bit of a rascal, a dreamer. I was Tom Sawyer, I was Huck Finn, on my way down the Mississippi. I remember stealing a piece of candy one time at the store. I was 6 or 7 years old. It was grandma candy wrapped in colorful cellophane, twisted on both sides. If you're a kid and you walk by, the color of that cellophane is really pretty. Sometimes the candy stuck out through the cracks of where it was boxed, and I thought, Maybe I'll just pull it all the way out. Before we left the store, my dad said, “I think you need to put that candy back. Why did you take it?” I said, “I was hungry.” And he said, “It's not yours, so the correct title is, you stole it.” His point was, you can justify anything. But if you put the correct title on it, it will help guide your decisions in life.

Q: You're working on a big multi-film project.

I'm pushing the rock uphill. It's epic in that it's four movies, all the same story, and it takes you to a place that you think you know, but you don't. I have it in my pocket as a great big secret that someday I will let people in on, and hopefully it will be something they never forget. It's poetic, it's violent, people acting on their worst instincts, acting on their best. It's raw. It's what I love about the West, the drama of it. It's not just about black hat or white hat.

Q: Why is fighting for creative integrity so important to you?

I have been tested in a lot of different ways. There have been very critical moments where I had to listen to myself and act and not be afraid of the outcome. I always put the audience on my shoulder. And I will say to Hollywood people, “Don't be too sure they don't want to see that.” And that's what the fight is about. I haven't always been really successful in certain movies. But I still love it.

Q: You and your country-rock band, Modern West, have recorded an album inspired by your show Yellowstone, called Tales From Yellowstone.

I grew up singing and playing music in the church, so that was my first love. The first band I was in, I was in my 20s and it was called Roving Boy. I was emerging as an actor and I got a terrible review, and it really shocked me. I'm not used to pulling back on any level, but I thought to myself, Do I need this kind of scrutiny? You know, the actor playing music. So I stepped away. I can't ever remember doing that, ever, but I stepped away.

Q: What brought you back from the musical winter?

My second wife discovered that early music and asked me, “Why don't you do this?” And I said, “Oh, no, no.” For two years, I backed away from it, like a kid who wouldn't eat his vegetables. She said, “Let me ask you something, are you happy when you're doing it?” And I said, “Yeah.” And she goes, “Do you think the people in front of you are happy?” And I said, “Yeah.” And she just looked at me and said, “Well what could be wrong with that?” So I called up two members of that original band, we're talking about 25 years later, and said, “I'm thinking of wanting to do music again.” And we started. We've been playing together for the last 16 years, around the world — South America, the Kremlin, the Grand Ole Opry three times. If it was just all up to me, the band wouldn't be very good. I play a really average guitar. I was trained on the piano, but I gave that up for sports. My mom said I'd be real sorry that I did that, and I was.

Q: You recently posted a song called “The Sun Will Rise Again."

I recorded that song live about two years ago in Ventura. We had these terrible fires and flooding where lives were lost in Santa Barbara from the boulders coming down the mountains. And that song just speaks to the hardship of things. And now with COVID-19, the whole world is feeling like this.

Costner performing with his band, Modern West.

Daniel Knighton/Getty Images

Q: How is performing as a singer different than as an actor?

Being with an audience and feeling like you have something to share makes me comfortable. Being in front of an audience posing makes me really uncomfortable. I don't want to be anywhere near that moment. I'm not saying I don't get nervous when I sing onstage, but I don't try to charm them to death. Unless you're just a narcissistic jerk, you love everybody's music more than your own. [Laughs.] When I listen to something, I think to myself, I have to do better.

Q: You write songs, screenplays. Have you written poems or fiction?

Yeah, but I look at it and it's not very good. I'm certainly not going to share that with anyone. I coauthored an illustrated novel called The Explorers Guild. You might like it. It's a bit of a slog. It's 800 pages, so ...

Q: You're really selling it. If you could be anywhere, where would that be?

I love what we've created, the homes that my wife and I have, but maybe Bora Bora. If I get dreamy, I like the idea of the Caribbean, of Polynesia. I dive on historical ships. I like the drama of what must have happened in that moment it went down, what people might have been thinking about when they don't have time to rearrange themselves. It's just part of the onion that's me.

Q: Who knows you best?

My wife.

Q: What do you wish that you were better at?

Getting it right.

Q: It seems like you're getting a lot right.

Yeah, but those things you don't, they can really foul you up. [Laughs.] I plan to play out the second half of my career with really big movies that take you somewhere, that have a level of poetry. There's a perception out there that I can do whatever I want, that things get easier for me professionally with age. It's simply not true. They don't. It's just as hard to make things now as it was when I was trying to make Dances. But I should do whatever I want. I'm at that spot in my life, artistically. I should be doing what pleases me.

Are we still talking about making movies?

Watching a movie, it's just something for us to grasp in the dark, just watching and going, Hmm, I didn't expect that. I'm glad I saw that. And then you've got to move on to the rest of your difficult day. But I want to be a part of that particular moment. What we yearn for, we all yearn for. I know that in my heart.

More on Entertainment

All Dogs Go to Kevin

Costner on his new canine character

Kevin Costner on 'The Highwaymen,' Aging, and Life Crossroads (Q&A)

The actor plays the retired Texas Ranger who caught Bonnie and Clyde, but he won't retire at 65