AARP Hearing Center

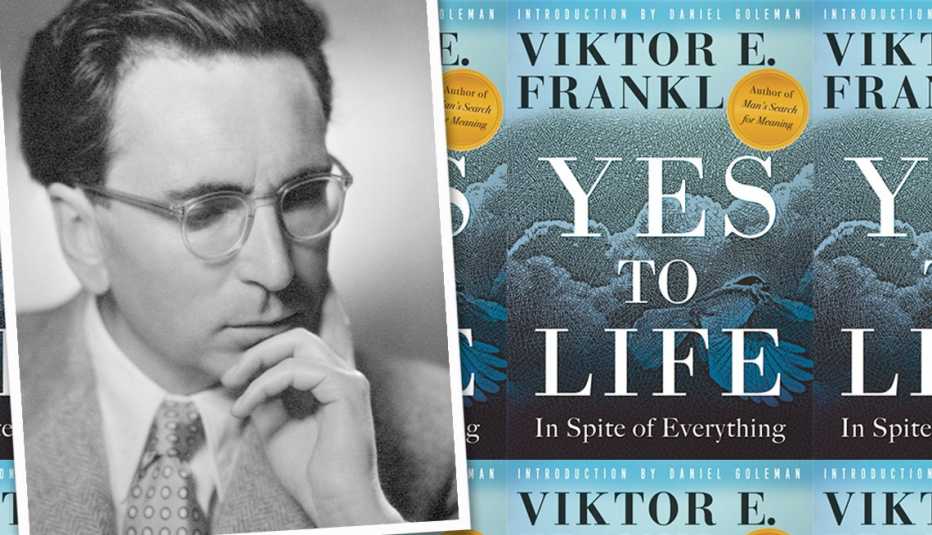

Viktor Frankl has inspired generations of readers since he first published the seminal Man’s Search for Meaning in 1946. In it, the psychiatrist describes his experiences in the Nazi death camp Auschwitz and how he and other prisoners managed to maintain hope, decency and reasons to live in the face of unimaginable horror.

Now there’s a newly published book of Frankl’s writings, translated into English for the first time, called Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything. Based on three public lectures Frankl gave in Vienna after he was released from prison, it further explains his insights on how life’s goal shouldn’t be happiness but a sense of purpose — a key pillar for well-being, he convincingly argued.

What follows is the introduction to Yes to Life by Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and author of the 1995 best seller Emotional Intelligence. He offers a beautiful summary of Frankl’s philosophy and why it’s just as relevant today as it was in 1946.

Introduction: Saying Yes to Life by Daniel Goleman

It’s a minor miracle this book exists. The lectures that form the basis of it were given in 1946 by the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl a scant nine months after he was liberated from a labor camp where, a short time before, he had been on the brink of death. The lectures, edited into a book by Frankl, were first published in German in 1946 by the Vienna publisher Franz Deuticke. The volume went out of print and was largely forgotten until another publisher, Beltz, recovered the book and proposed to republish it. Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything has never before been published in English.

During the long years of Nazi occupation, Viktor Frankl’s audience for the lectures published in this book had been starved for the moral and intellectual stimulation he offered them and were in dire need of new ethical coordinates. The Holocaust, which saw millions die in concentration camps, included as victims Frankl’s parents and his pregnant wife. Yet despite these personal tragedies and the inevitable deep sadness these losses brought Frankl, he was able to put such suffering in a perspective that has inspired millions of readers of his best-known book, Man’s Search for Meaning — and in these lectures.

He was not alone in the devastating losses and his own near death but also in finding grounds for a hopeful outlook despite it all. The daughter of Holocaust survivors tells me that her parents had a network of friends who, like them, had survived some of the same horrific death camps as Frankl. I had expected her to say that they had a pessimistic, if not entirely depressed, outlook on life. But, she told me, when she was growing up outside Boston her parents would gather with friends who were also survivors of the death camps — and have a party. The women, as my Russian-born grandmother used to say, would get “gussied up,” wearing their finest clothes, decking themselves out as though for a fancy ball. They would gather for lavish feasts, dancing and being merry together — “enjoying the good life every chance they had,” as their daughter put it. She remembers her father saying “That’s living” at even the slightest pleasures.

As she says, “They never forgot that life was a gift that the Nazi machine did not succeed in taking away from them.” They were determined, after all the hells they had endured, to say “Yes!” to life, in spite of everything.

The phrase “yes to life,” Viktor Frankl recounts, was from the lyrics of a song sometimes sung sotto voce (so as not to anger guards) by inmates of some of the four camps in which he was a prisoner, the notorious Buchenwald among them. The song had bizarre origins. One of the first commanders of Buchenwald — built in 1937 originally to hold political prisoners — ordered that a camp song be written. Prisoners, often already exhausted from a day of hard labor and little food, were forced to sing the song over and over. One camp survivor said of the singing, we “put all our hatred” into the effort.

But for others some of the lyrics expressed hope, particularly this:

. . . Whatever our future may hold:

We still want to say “yes” to life,

Because one day the time will come —

Then we will be free!

If the prisoners of Buchenwald, tortured and worked and starved nearly to death, could find some hope in those lyrics despite their unending suffering, Frankl asks us, shouldn’t we, living far more comfortably, be able to say “Yes” to life in spite of everything life brings us? That life-affirming credo has also become the title of this book, a message Frankl amplified in these talks. The basic themes that he rounded out in his widely read book Man’s Search for Meaning are hinted at in these lectures given in March and April of 1946, between the time Frankl wrote Man’s Search and its publication.

For me there is a more personal resonance to the theme of Yes to Life. My parents’ parents came to America around 1900, fleeing early previews of the intense hatred and brutality that Frankl and other Holocaust survivors endured. Frankl began giving these talks in March of 1946, just around the time I was born, my very existence an expression of my parents’ defiance of the bleakness they had just witnessed, a life-affirming response to those same horrors.

In the rearview mirror offered by more than seven decades, the reality Frankl spoke to in these talks has long gone, with successive generational traumas and hopes following one on another. We postwar kids were by and large aware of the horrors of the death camps, while today relatively few young people know the Holocaust occurred.

Even so, Frankl’s words, shaped by the trials he had just endured, have a surprising timeliness today.

Frankl’s main contribution to the world of psychotherapy was what he called “logotherapy,” which treats psychological problems by helping people find meaning in their lives. Rather than just seeking happiness, he proposed, we can seek a sense of purpose that life offers us.

Happiness in itself does not qualify as such a purpose; pleasures do not give our life meaning. In contrast, he points out that even the dark and joyless episodes of our lives can be times when we mature and find meaning. He even posits that the more difficult, the more meaningful troubles and challenges can be. How we deal with the tough parts of our lives, he observes, “shows who we are.”

If we can’t change our fate, at least we can accept it, adapt, and possibly undergo inner growth even in the midst of troubles. This approach was part of a school known as “existential therapy,” which addresses the larger issues of life, like dealing with suffering and dying — all of which Frankl argued are better handled when a person has a clear sense of purpose. Existential therapies, including Frankl’s version, blossomed particularly as part of the humanistic psychology movement that peaked in the 1970s and continued in successive decades. To be sure, a robust lineage of logotherapy and existential analysis continues to this day.

There are three main ways people find fulfillment of their life meaning, in Frankl’s view. First, there is action, such as creating a work, whether art or a labor of love — something that outlasts us and continues to have an impact. Second, he says, meaning can be found in appreciating nature, works of art, or simply loving people; Frankl cites Kierkegaard, that the door to happiness always opens outward. The third lies in how a person adapts and reacts to unavoidable limits on their life possibilities, such as facing their own death or enduring a dreadful fate like the concentration camps. In short, our lives take on meaning through our actions, through loving, and through suffering.

Frankl cites a converging formulation from Rabbi Hillel almost two thousand years ago. The translation I know best goes: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am not for others, what am I? And if not now, when?” For Frankl, this suggests that each of us has our unique life purpose and that serving others ennobles it. The scope and range of our actions matter less than how well we respond to the specific demands of our life circle.

A common thread in these disparate words of wisdom comes down to the ways we respond to life’s realities moment to moment, in the here and now, as revealing our purpose in an ethics of everyday life. Our lives continually pose the question of our life’s meaning, a query we answer by how we respond to life.

To be sure, Frankl saw human frailty, too. Each of us, he notes, is imperfect — but imperfect in our own way. He put a positive spin on this, too, concluding that our unique strengths and weaknesses make each of us uniquely irreplaceable.

--------------

In light of the wholesale madness that afflicted too much of the “civilized” world during the great war that had just passed, Frankl felt the younger generation of his day no longer had the kind of role models that would give them a sense of enthusiastic idealism, the energy that drives progress. The young people who had witnessed the war, he felt, had seen too much cruelty, pointless suffering, and devastating loss to harbor a positive outlook, let alone enthusiasm.

The years leading up to and including the war, he noted, had “utterly discredited” all principles, leaving the nihilistic perception that the world itself lacked any substance. Frankl asked how it might be possible to resurrect and sustain concepts like a noble meaning in life, which had been so wantonly demolished by a torrent of lies.

In another timely insight, Frankl saw that a materialistic view, in which people end up mindlessly consuming and fixating on what they can buy next, epitomizes a meaningless life, as he put it, where we are “guzzling away” without any thought of morality. That very eagerness for consumption has become today a dominant worldview, one devoid of any greater meaning or inner purpose.

Add to that the degradation of human dignity created by an economic system that had, in the last few decades before Frankl gave his talks, relegated working men and women into “mere means,” degrading them into “tools” of making money for someone else. Frankl saw this as an insult to human dignity, arguing that a person should never become a means to an end.

And then there were the concentration camps, where lives seen only as worthy of death were nevertheless exploited as slave labor to their biological limits. From all that — plus the simple fact of collusion with evil leaders — European countries especially were pervaded by a collective sense of guilt. On top of all this, Frankl was acutely aware as a camp survivor that “the best among us” did not return. That knowledge could easily turn into a crippling “survivor’s guilt.” Small wonder camp survivors like him had to relearn how to be happy at all.

From all these insults to reach any sense of meaning ensued an inner crisis, as Frankl sensed, one that led to the comfortless worldview of a nihilistic existentialism — think Beckett’s bleak postwar play Waiting for Godot, an expression of the cynicism and hopelessness of those years. As Frankl put it, “It should not be a surprise if contemporary philosophy perceives the world as though it had no substance.”

Fast-forward seven decades or more. These days, various lines of evidence suggest that many young people today are putting their sense of meaning and purpose first — a development Frankl could not have foreseen given the dark lens that the horrors he had just survived gave him. But these days, those who recruit and hire for companies, for instance, report that more than any time in memory the new generation of prospective employees shun working for places whose activities conflict with their personal values.

Frankl’s intuitive sense of how purpose matters has been borne out by a large body of research. For instance, having a sense of purpose in life offers a buffer against poor health. People with a life purpose, data shows, tend to live longer. And researchers find that having a purpose numbers among the pillars of well-being.

“Whoever has a why to live can bear almost any how,” as the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche declared. Frankl takes this maxim as an explanation for the will to survive he noted in some fellow prisoners. Those who found a larger meaning and purpose in their lives, who had a dream of what they could contribute, were, in Frankl’s view, more likely to survive than were those who gave up.

One crucial fact mattered here. Despite the cruelty visited on prisoners by the guards, the beatings, torture, and constant threat of death, there was one part of their lives that remained free: their own minds. The hopes, imagination, and dreams of prisoners were up to them, despite their awful circumstances. This inner ability was real human freedom; people are prepared to starve, he saw, “if starvation has a purpose or meaning.”

The lesson Frankl drew from this existential fact: our perspective on life’s events — what we make of them — matters as much or more than what actually befalls us. “Fate” is what happens to us beyond our control. But we each are responsible for how we relate to those events.

Frankl held these insights on the singular importance of a sense of meaning even before he underwent the horrors of camp life, though his years as a prisoner gave him even deeper conviction. When he was arrested and deported in 1941, he had sewn into the lining of his overcoat the manuscript of a book in which he argued for this view. He had hoped to publish that book one day, though he had to give up the coat — and the unpublished book — on his first day as a prisoner. And his desire to one day publish his views, along with his yearning to see his loved ones once again, gave him a personal purpose that helped keep him afloat.

After the war, and with this optimistic outlook on living still intact despite the brutalities of the camps, Frankl in these lectures called on people to strive toward “a new humanity,” even in the face of their losses, heartbreaks, and disenchantments. “What is human,” he argued, “is still valid.”

Frankl recounts asking his students what they thought gave a sense of purpose to his, Frankl’s, own life. One student guessed it exactly: to help other people find their purpose. Frankl ended these lectures — and this book — by saying his entire purpose has been that any of us can say “Yes” to life in spite of everything.

Excerpted from Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything by Viktor Frankl. Copyright 2020. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.

Available at Amazon.com, Bookshop.org (where your purchase supports independent bookstores), Barnes & Noble (bn.com) and wherever else books are sold.

More From AARP

AARP’s Best Books of 2023 (So Far)

10 of our books editor’s top picks, plus 3 honorable mentions