AARP Hearing Center

Fifty years ago, after the commercial failure of his first two albums, Bruce Springsteen released his iconic album Born to Run. Born — bookended by “Thunder Road” and the epic “Jungleland” — leaped up the charts, and Springsteen was launched into superstardom. At the center of the Boss’s masterpiece was the gorgeously wrought summer anthem “Born to Run.”

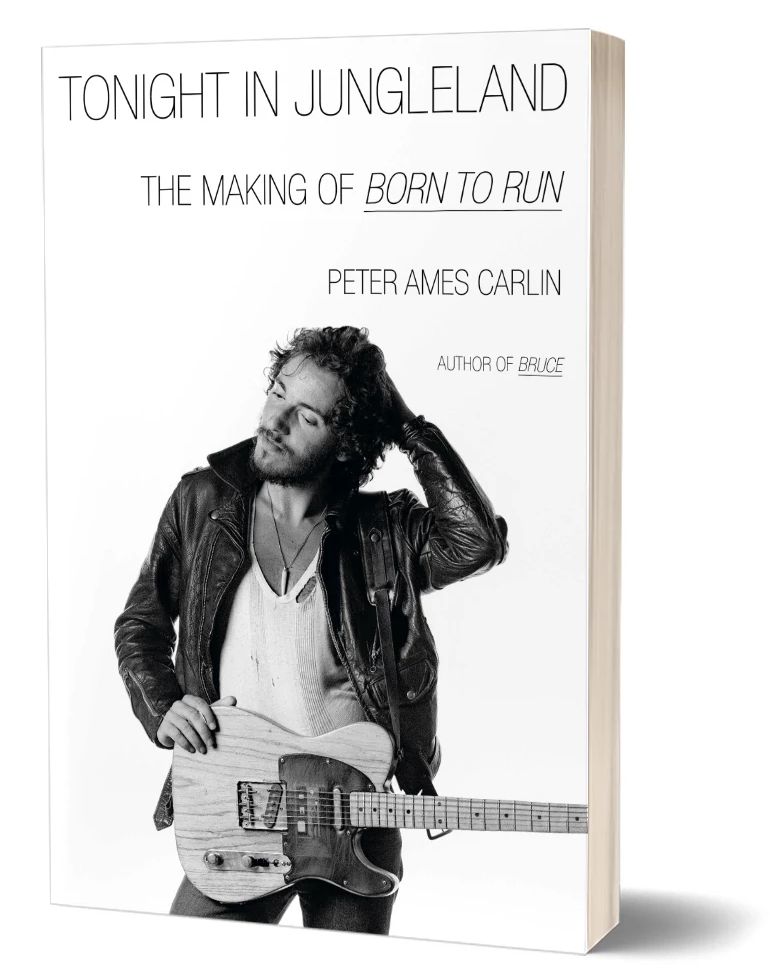

Here’s its somewhat fraught two-year creation story, adapted from my new book, Tonight in Jungleland. (Editor’s note: Read our interview with Carlin for more on the birth of Born to Run.)

From 'Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run'

On a page in his notebook, the song was coming together. It was fall of 1973 and Bruce Springsteen was in Asbury Park, watching the street racers in their souped-up cars orbiting the Ocean Avenue/Kingsley Street circuit on a Saturday night.

The parade of muscular, lovingly detailed automobiles stirred something in him — the way the cars animated their owners’ spirits. The candy shades of red, purple, and blue, the racing stripes and hand-painted eagles, the dazzling chrome and shimmering glass. And the power of their engines: the low rumble as they idled, the jet roar of takeoff. Like animals pacing in a black, dark cage, senses on overload … / They’re gonna end this night in a senseless fight / And then watch the world explode.

Circling and revving, drifting slowly and then blasting off. Where were they going? It was an interesting question, just as compelling as where they came from and what brought them out into the night, to circle with their friends and rivals, to put it all on the line.

One car had words running down its flank, a chain of cursive letters canted forward as if pulled by the finish line off in the distance. A dare, a philosophy, an explanation. Did he actually see it on a passing racer? Or did it simply pop into his head? Bruce wrote it into his notebook, in case he forgot it. He’d never forget it.

Born to run.

By the end of 1973, Bruce Springsteen was in a tough spot. His first album on Columbia Records, Greetings From Asbury Park, N..J., had been released that January. Critics and a small cadre of fans had loved it, and his second album, The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle, released that fall, won the same acclaim, but also the same weak sales. That hard fact, along with a shift in Columbia Records’ upper management, meant that Bruce had fallen increasingly out of step with his record company. It was taking longer and longer for his manager, Mike Appel, to get his calls returned. Especially now that he was trying to figure out when they’d be getting the money they’d need to fund recording sessions for Bruce’s next album.

When he finally got an answer in the early weeks of 1974, the news was frustrating, at best. Go make a single, they said. If it sounds like it could be on the radio, we’ll pay for the rest of the album. Appel tried to protest: Bruce isn’t a singles act, he argued. It’s all about albums; that’s been the plan all along. But that hadn’t worked, the executives said. So this is your chance. Go make a single.

Bruce, then 24, was particularly close to Appel and trusted him so implicitly, he barely read the contracts his new manager gave him to sign. The two made an unlikely but surprisingly well-matched pair. Appel was a few years older, with shorter hair, neater clothes, and the restless energy of a man who was trying to get somewhere else. Bruce was just as ambitious but moved through the world more quietly. He talked less, tended to the edges of the room, and kept watch. When something caught his eye, he reached for his notebook and clicked open his pen. You never knew what he was seeing, what he was thinking, not until he stepped onto the stage, saw his musicians around him, and counted to four.

But Bruce knew he had in Appel an advocate, a protector, and a record producer. “His heart was in it, and everything else,” Bruce told me. “That’s part of what attracted me, because it was all or nothing.” Now that the executives at Columbia had made it clear that his recording contract was on the line, Bruce wanted to make certain his new songs had the economy and drive to fit on the radio. He would need to hone his style to make his songs sleeker, faster, and more powerful. Like the singles Phil Spector made in the early 1960s. What did he need to do to get there?

Appel had thoughts. Spector songs had lyrics that were direct, first person, conversational, he told Bruce. They left plenty of space between for the melody to come through. Bruce’s songs, like “Blinded by the Light,” sounded like lyrical Gatling guns: words upon words upon words. “But you can’t do that with a Phil Spector production,” Appel said.

Bruce absorbed it, nodded, picked up his notebook. He had a new song that felt different from what they’d done before. He wasn’t done with it yet, but the bones, and the essential feelings, were there. The chords for the song, and the melody of theverses, found their shape nearly immediately. In one early draft, titled “Wild Angels,” the verses describe a litany of modern urban catastrophes. Murderous junkies turn shotguns on soldiers on leave from Fort Dix.

Them wild boys did it just for the noise.

Not even for the kicks. Roads crumble, drivers are crushed beneath their own cars. The game is so rigged, it’s murderous.

This town’ll rip the bones from your back. It’s a death trap.

You Might Also Like

AARP’s Favorite 2025 Books (So Far)

AARP’s books editor shares her top 10 reads

The 75 Essential Books for Gen Xers

Remembering the reads that entertained us, taught us and shaped us into who we’ve become

Stephen King’s ‘Never Flinch’ Is a Gripping Detective Tale

The master of the macabre has done it again in his latest novel