AARP Hearing Center

At 42, Kate Washington was a busy freelance writer whose younger daughter was just starting kindergarten — a shift she hoped would give her more time to focus on her career. But life had other plans. When her husband, Brad, was diagnosed with a rare T-cell lymphoma, she experienced what she jokingly refers to as a “very inconvenient midlife crisis.” The news from the oncologist plunged her into the world of caregiver, one with ups and downs, guilt, fear and vigilance that added to her already full life.

"My children were 9 and 5 when Brad was diagnosed,” says Washington during a phone interview. “I had just begun to feel like we'd made it out of the hard part of parenting and into the elementary years. Caring for someone else beyond my children was the furthest thing from my mind.”

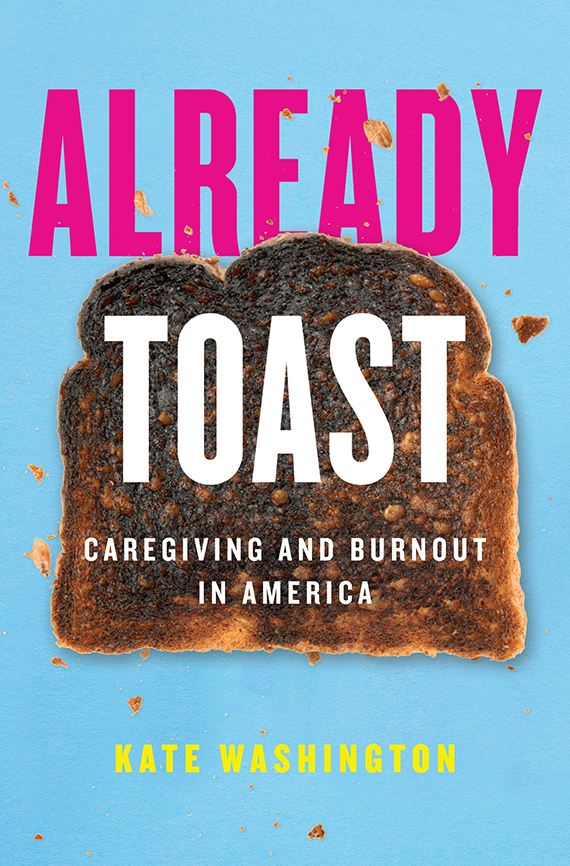

In her recent book, Already Toast: Caregiving and Burnout in America, Washington chronicles how Brad's diagnosis upended any sense of security she had. She writes powerfully about the initial shock and how long it took for her to come to terms with the kind of intensive care he was going to need.

"There was so much uncertainty,” she says. “When is the moment when you flip from not being someone's caregiver to their caregiver? Is it when you start going to medical appointments, calling the insurance company or administering medication?”

The emotional roller coaster

In the book, which is part memoir and part study on the role unpaid caregivers play in a society without structural and financial support, Washington perfectly describes the emotions and activities that so many caregivers experience. She articulates some of the ugly, highly personal and often shameful emotions caregivers feel at times.

"You can question yourself a lot,” says Washington. “Am I unkind? Am I lacking in something? Why am I struggling with the demands of the situation? Working through those emotions without a model can be isolating and challenging.”

There is a poignant moment in the book when Washington contemplates just driving away from the house and not coming back, a fantasy with which I could relate having cared for my own husband after a life-threatening injury.

"There is a time when the mutuality of partnership has to fade away because the physical needs of the person in the moment must come first,” she says. “In a partnership or a relationship you end up giving, but normally you get back things in terms of sustaining or mutual ability to support one another. When your loved one is incapacitated and can no longer function the way they used to, you have lost your primary support at the exact time you are going through something really, really hard.”