AARP Hearing Center

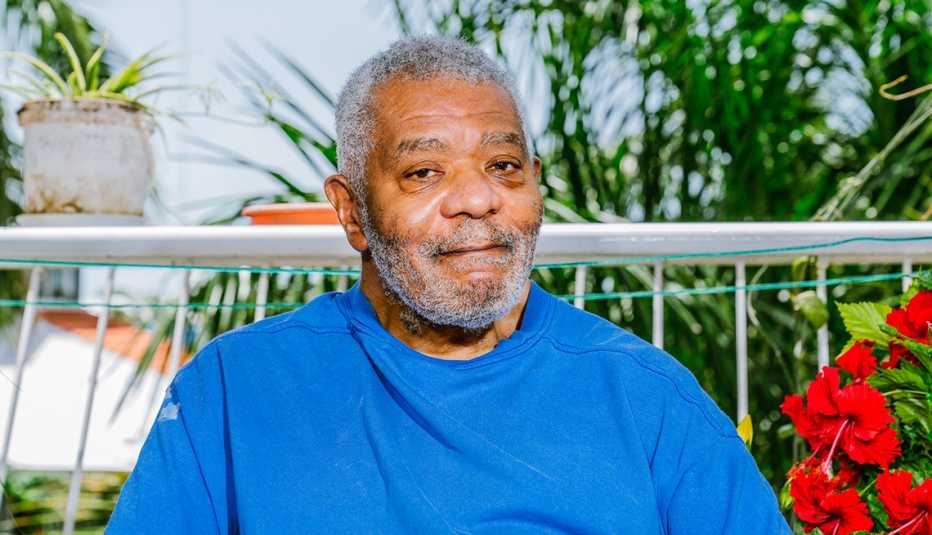

Mia Yamamoto, 78, did not set out to make history as a transgender trial lawyer. In fact, as a young person Yamamoto was not even sure that she would finish college. Born a boy in the Poston Relocation Center internment camp, where families of Japanese descent were sent during World War II, Yamamoto often felt like an outsider growing up in Los Angeles and initially failed out of college. After getting a degree, she enlisted in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. After that, she earned a law degree and later worked for the Los Angeles Public Defender’s Office. In 2003, at age 60, Yamamoto came out as transgender, becoming the first openly trans trial lawyer in the state of California. This is her story.

Trans Activism Moves Ahead

1966: A riot at Compton’s Cafeteria in the Tenderloin District of San Francisco marked the beginning of transgender activism. The riot took place in response to law enforcement harassment of drag queens and trans and gay people who were in the restaurant. It’s one of the first reported instances of transgender people fighting against oppressive actions.

1969: The Stonewall uprising, a struggle between members of the New York City queer community and cops following a raid on the famous bar kicks off the modern LGBTQ+ Liberation Movement.

1970: Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, two transgender sex workers, started Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, and then created STAR House, in New York City, which worked to provide housing for street queer and trans youth.

1975: Minneapolis protects transgender people with a nondiscrimination ordinance prohibiting employment discrimination and equal access to public accommodations — the first such law in the country.

1993: Minnesota extends the nondiscrimination law to the entire state.

2005: California bars medical insurance companies from denying transgender people health care with the Insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act.

2008: Stu Rasmussen, of Silverton, Oregon, is elected the nation’s first openly transgender mayor.

2014: Obama Administration rules that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act applies to transgender people, affording federal nondiscrimination protections to the transgender community.

The Obama Administration also rules that Medicare must cover gender-confirmation surgeries.

2020: The Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, decision by the U.S. Supreme Court affirms that Title VII protects transgender people from being fired from their place of work for transitioning.

2021: Rachel Levine became the first openly transgender person confirmed by the U.S. Senate to a federal post and was sworn in as the assistant secretary of health. The same year, Levine became the first openly transgender four-star officer across the country’s eight uniformed services.

Mia Yamamoto: [My first memories are] a recollection of the resettlement from Poston internment camp. After being locked up, all of us were able to get back to some form of life and start over again. I certainly experienced a lot of the discrimination. Because being Japanese was probably the most uncool thing you could imagine in postwar East Los Angeles.

With the queer identity, of course, you find out that you’re trans about, oh, 5 years old, usually. Your early growing up is torture — you’re trying to fit into a place where you don’t fit in. And you start to believe there’s no place for you. Especially trans kids, because that’s a pretty minuscule minority.

I think just being a queer kid is different. And you grow up differently, and your brothers treat you differently, because you have a different, I guess what you would call, style. My brothers were tough. But I will say this, having to fight my brothers really taught me how to fight. I really learned how to take care of myself on the street.

I lived through those early years, just flopping around from school and being a disappointment to everybody, especially my teachers. My grades were really bad, but I did succeed in graduating high school. Eventually, I graduated L.A. City College and I went to Cal State.

And then I went into the Army because the Vietnam War was going on. I came back from the war and I had to do something. So I went to law school — I wanted to do what my dad did. I wanted to continue his legacy. He was a member of the NAACP. He was an ACLU lawyer. His ideal was to always do the most noble thing, and that was to work for the poor.

I was a part of the anti-war movement because I was really guilt-ridden about what I had been a part of. I think I still am. So the anti-war movement was the first place I went to — but the movement for racial and social justice was all around that. Eventually, I went to the public defender’s office. I needed something to make me want to get up in the morning and needed a sense of purpose. And the work did that for me. Working for poor people in the criminal courts gave me a sense of purpose.