AARP Hearing Center

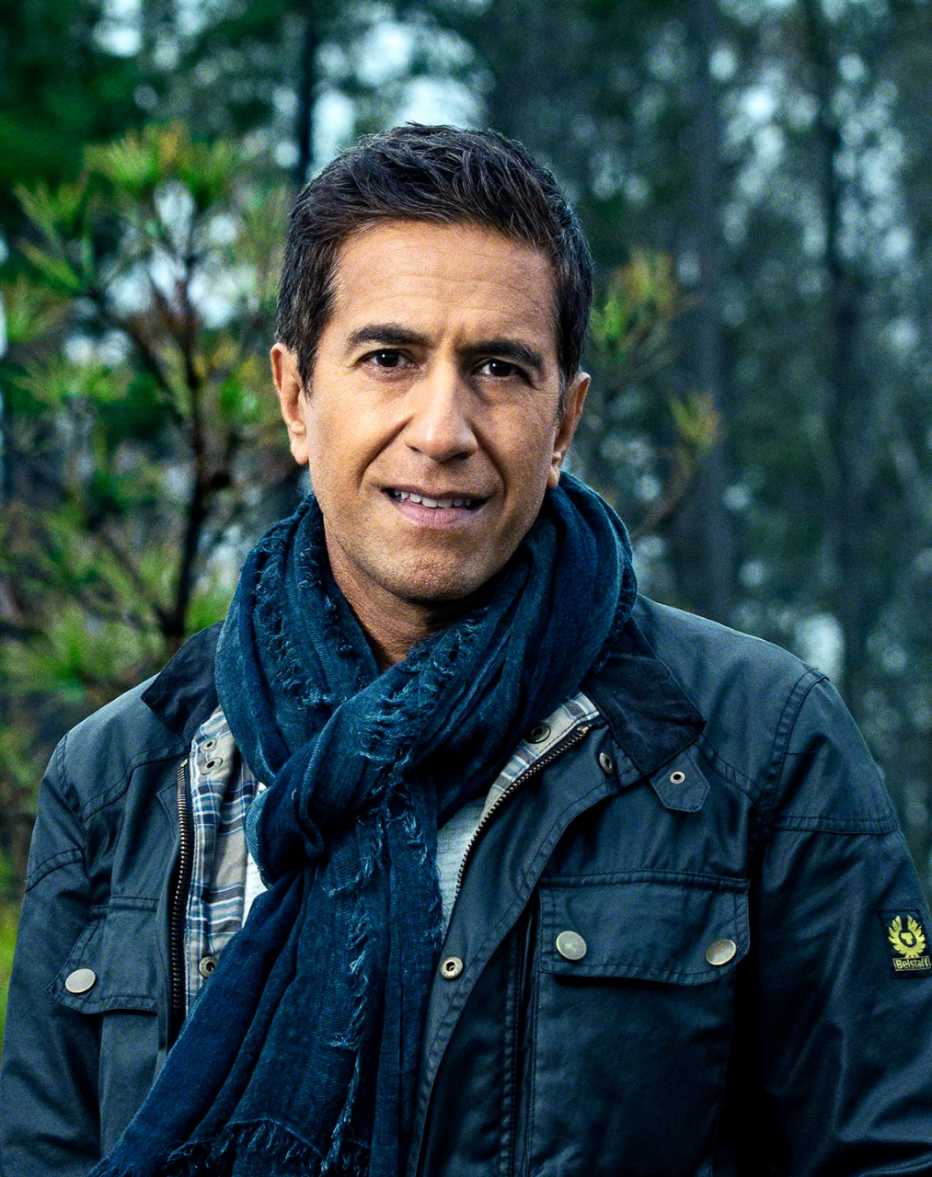

After 20 years of practicing medicine, Michael J. Stephen, M.D., thought he had seen everything. Then COVID-19 hit his hospital.

And then it hit him.

A critical care pulmonologist at Thomas Jefferson University's Jane and Leonard Korman Respiratory Institute in Philadelphia, Michael had been caring for patients while protecting himself as best he could. Then he woke up one Saturday morning in May with a sore throat. By dinnertime, he was coughing, and an hour later, he spiked a fever of 103 degrees. “Where did I slip up?” he kept asking himself, agonizing over having brought COVID-19 home to his two school-age children and wife, all of whom subsequently became sick.

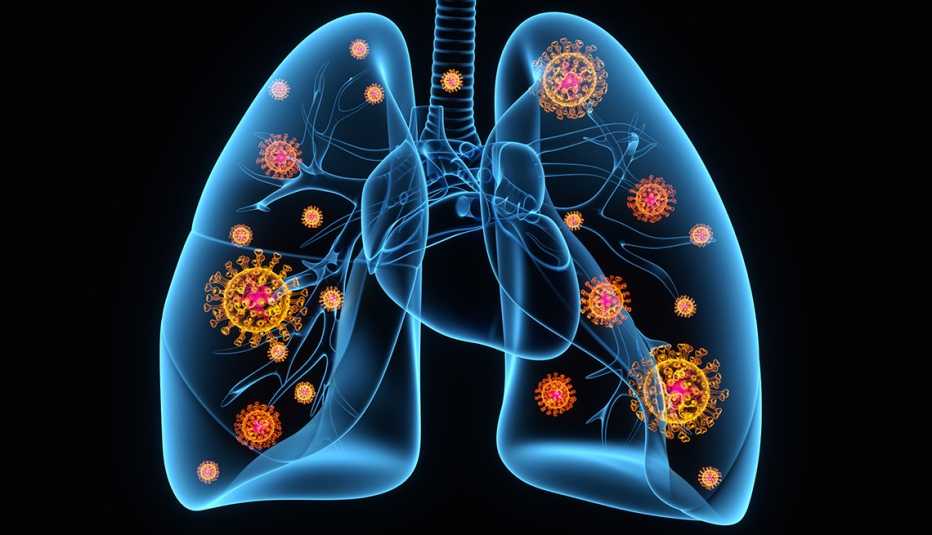

His family recovered relatively quickly, but Michael, 47, who had been triathlon-fit prior to the infection, wound up hospitalized, with a left lung filled with blood clots and a brain stuck in a deep fog. Indeed, he felt like he was losing his mind. The splitting headaches and overwhelming fatigue convinced him his brain was on fire.

"I was doing things I wasn't aware of,” he now recalls. “I talked out loud in my room during isolation, and my wife kept asking me who I was talking to on the phone. I said nobody, not realizing that I was vocalizing the normal running dialogue we all have with ourselves. I remember thinking several times that I needed to tell my wife to keep my father away from the house — that he has cancer and that he could die if he came over. He did have cancer, but he died in 2007."

Michael recuperated after six rocky, roller-coaster weeks. Nonetheless, he feels like something has been forever changed in his body. “There's always a bit of a whisper in the back of my mind, wondering if there will be long-term effects. Something could happen down the line.” He also thinks of his family members, who could now bear new risks for future health problems.

His anxieties are valid. Four-fifths of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have neurological symptoms, and although estimates vary, studies have found that at least half of people who recover from COVID-19 continue to suffer from neurological symptoms for months after. Brain scans of patients, compared with scans of those who've never been infected, show structural and functional changes to the brain. We don't know yet what that means for these patients’ long-term prognosis, but the medical community is serious about figuring it out. A global consortium of research scientists has been established to study the relationship between COVID-19 and neurological dysfunction. Their work has taken on greater urgency over the past few months, as we grapple with the fact that even those in the highest reaches of government and the military aren't safe from this virus.