AARP Hearing Center

Editor’s note: This essay won first place in the 2025 Big Brick Review essay contest.

I’m driving 300 miles upstate, wearing a gauze bandage and bringing home a bag of my sister’s hair.

Meadowbrook, Huntington, Cuomo Bridge. The New York exits fall behind me before I stop in Monticello, where the March snow is still piled high, the edges melting. At last I feel the pull of home, a place of broad lakes and unplanted fields, three weeks behind New York City in warmth and tulips.

My 67-year-old sister, Ginny, needs a bone marrow transplant, her one chance for a cure. And I am her perfect match. At 64, I don’t understand the science, but didn’t hesitate to say yes. Just two days prior, I was hooked up to a device that took my blood, spun out precious stem cells and — click-click-click — returned the rest to my veins. I read a book, ate oatmeal cookies and chatted with the nurses the whole time.

I don’t need these cells, at least not in the numbers induced by the drug I’ve been taking for five days. At the end of the procedure, the nurse shows me a bag of filtered blood and tells me it contains nearly 8 million of my stem cells.

“Your platelets are low, so don’t do anything strenuous for a day or two,” she says. “They grow back quickly.”

“I guess it’s not time to get that tattoo,” I say, and we both laugh.

Ginny needs these cells to save her life. After killing her bone marrow, doctors will infuse her with my cells, wait a couple of months, then a year, and see how well they take. There are no guarantees, but a sibling match is her best chance.

“A perfect 10,” they call me. I’ve never been perfect in my life.

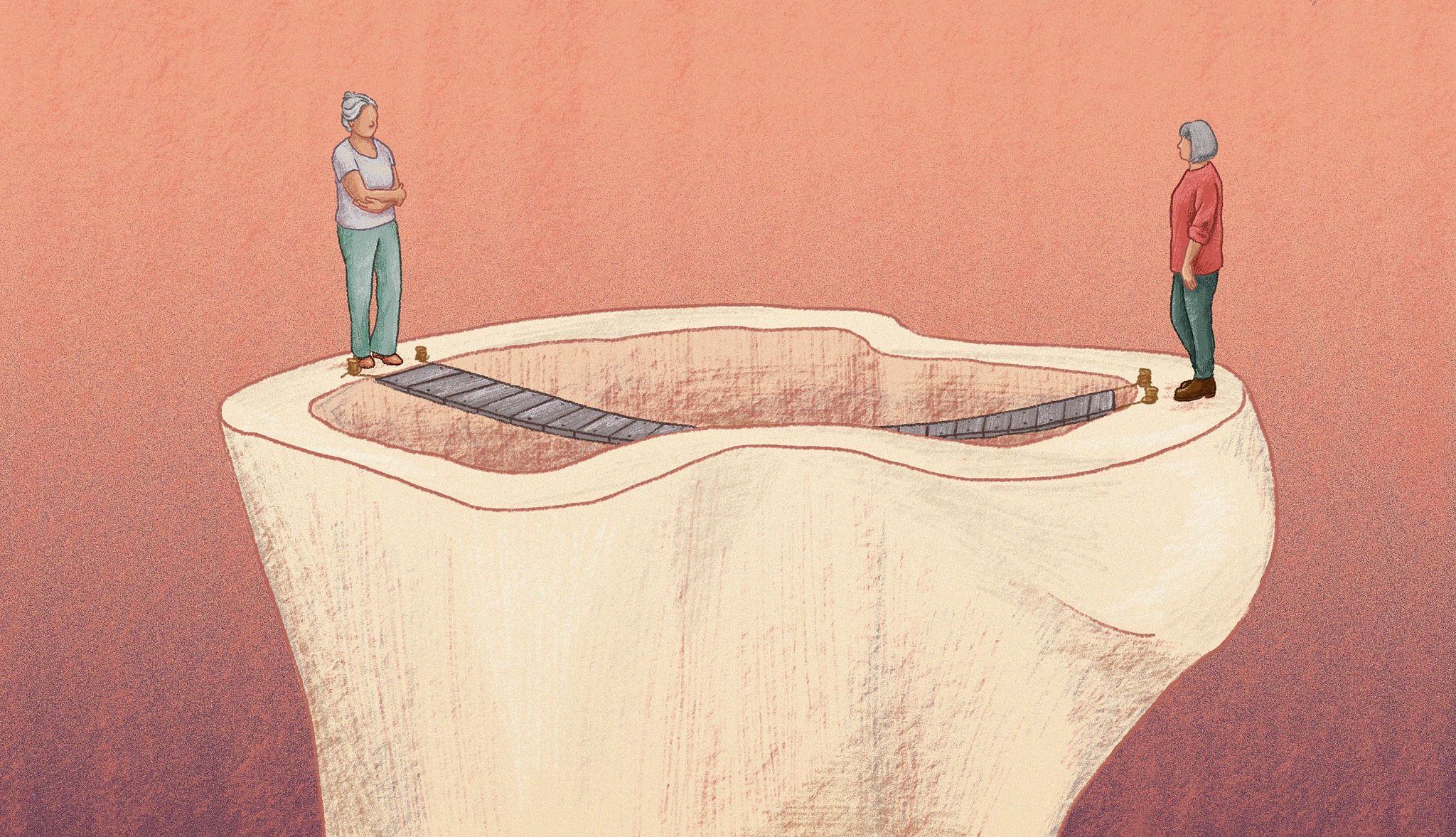

Finding common ground

Ginny and I are mismatched in so many other areas of life. Our political views have driven us into corners, fighting like wolverines. I read online about how to survive Christmas if the reds and blues of the family do battle. It has only gotten worse.

You Might Also Like

I’ve Been Trying Yoga. I’m Tied Up in Knots

A retired journalist finds Improving flexibility can be a stiff order after 60

New Boo and Old Friends at Odds?

You’re in love with your new partner but your friend, not so much. Here’s how to handle it

Here's How to Tame Your Fear of Death

Leaving this world doesn't have to be scary. Here's how to cope