AARP Hearing Center

Rosanne Cash crashed into country music in 1979 as a hybrid artist, balancing the Tennessee roots of her father with her California upbringing and an edgy, urban sensibility gleaned from a short stint living in England.

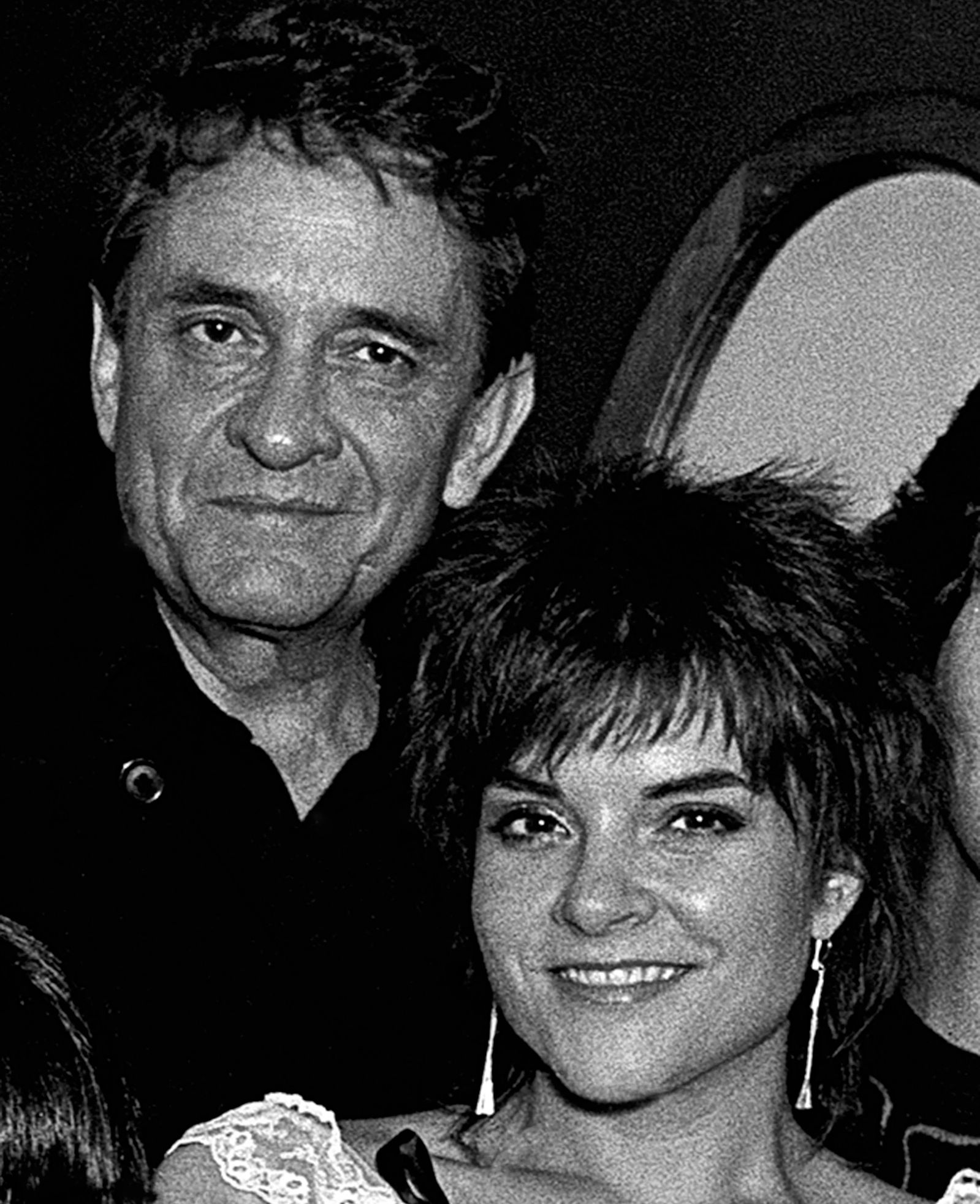

Though she was Johnny Cash’s daughter, she was desperate to step out of his shadow and set herself apart from traditional Nashville music, something her progressive debut album, Right or Wrong, clearly proved. But it was her follow-up record, 1981’s Seven Year Ache, a commercial and critical bombshell set to soul-searching vocals, that established her as an adventurous, fiercely creative songwriter whose work transcends genres.

Through the years, with such albums as 1993’s The Wheel and 2014’s The River & the Thread (all made with her husband, producer John Leventhal), she deepened her reputation as a literary songwriter and expanded her ambitious sonic landscape. A four-time Grammy winner, Cash, also the author of the elegant memoir Composed, in 2021 became the first woman to receive the Edward MacDowell Medal for music composition.

Cash is currently the subject of a major exhibition, Rosanne Cash: Time Is a Mirror, through March 2026 at Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame. She released Rosanne Cash: The Essential Collection on her own RumbleStrip Records. She recently spoke to AARP from her home in New York.

Telling stories — all of them

My parents were very young and extremely poor when I was born. My mother had two dresses. And they had one fountain pen, which they had to share. Dad took it to work, so Mom couldn’t write anything down until he brought it home. And then my dad went on the road all the time. My mom had a lot of anxiety about that. And about my dad starting fires. Once the whole hillside burned, which was an accident — he was driving his tractor through dry brush. I still remember the feel of the smoke in my chest and how I couldn’t sleep because my chest hurt so much. And my mother suspected my dad was having affairs, and when he got with June Carter, it was clear that he was moving away. My mother was depressed and anorexic, and probably had a borderline personality. So I had to become an adult, caring for my three younger sisters, and if my mom had three people to play cards, they’d call me to come be the fourth. As an artist, I don’t believe you have to keep suffering. But I think the original wounds can be source material, a place that’s open.

Find your path

I love language. I love grammar and punctuation, the Oxford comma, the sound of words. Onomatopoeia. Shakespeare. At 4, I desperately wanted to go to school. I asked my mother about every word I saw. I wanted to go to the library and read. There was so much going on at home that I tried to find safety in my imaginary life and in the library and in books and music, particularly when I got to be in my early teens. All that was refuge, and it seeded the inspiration for later.

Learning what’s normal

I had dreams as a kid that I was going to do something different with my life. I was never, ever the girl who bought bride magazines or fantasized about a dress or a wedding. So for a long time, I felt like not a real girl. John [Leventhal, her husband] says that I “front” normal. Coming from such an abnormal childhood, I worked really hard at being normal my whole life. I would think to myself: “What do people do on New Year’s Eve? They drink champagne. OK, I’ll do that.” It’s the reason I love the Little House books. It’s washing on Monday, scrubbing on Tuesday, baking on Wednesday.

You Might Also Like

David Schwimmer is Happy to be a Homebody

Former 'Friends' star discusses why he's commited to staying close to his NYC home and his new role in 'Goosebumps' movie

Michael J. Fox’s Guide to Being a Survivor

The star has lived with Parkinson’s since 1991, but hasn’t lost any of his spirit or humor

How One Man Beat Despair, One Lawn at a Time

He lost his job, but providing free yard work for others in need gave him back a sense of purpose