AARP Hearing Center

In a small town in Maine, a paid in-home caregiving aide’s shift ends at 2 p.m. The worker leaves a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for the client’s dinner. A cooler with drinks sits by the bed.

In another part of the state, a veteran coping with incontinence is unable to find a care worker to help him. He sleeps on trash bags and relies on a housemate to help him get to the bathroom.

America is facing a shortage of in-home caregiving aides — professionals who perform a multitude of tasks to help aging people unable to fully care for themselves in their homes, either because they have no family to help or to supplement family care. That shortage is particularly apparent in Maine, which has the highest percentage of residents 65 and older in the United States. Nearly 11,000 hours of personal care are going unstaffed each week in the state. And at two of its health systems, at least 100 people each week can’t be discharged from hospitals because they won’t get the necessary post-treatment care, according to Jess Maurer, executive director of the Maine Council on Aging.

“It’s heartbreaking,” says Betsy Sawyer-Manter, CEO of SeniorsPlus, the designated Area Agency on Aging for western Maine. “Some people simply go without care.”

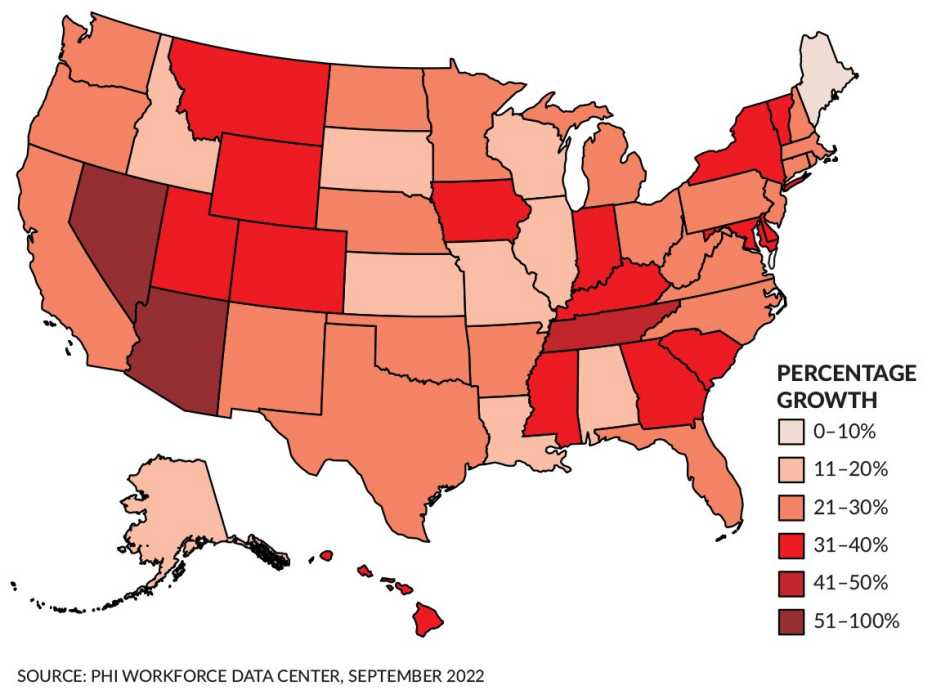

Need for in-home aids expected to grow dramatically

Maine is not the only state facing a critical caregiving shortage. In Wisconsin, 23,165 caregiving positions are open throughout the state, but only 19,600 people in that state who are not currently in the labor force are looking for work of any kind. At the Area Agency on Aging in Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania (total population roughly 215,000), 33 people are on a waiting list for caregiving help. One person has been on that list for a year.